- Advancing Second-Line Therapy in Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) remains one of the most aggressive malignancies, characterized by high relapse rates and a dismal prognosis, particularly in the second-line setting, where standard therapies offer limited benefit. Despite available treatments such as topotecan and Lurbinectedin, median overall survival rarely exceeds six months. The chemotherapy-free interval (CTFI) plays a pivotal role in guiding second-line treatment, stratifying patients for either platinum rechallenge or non-platinum regimens. Bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs), including tarlatamab, have demonstrated encouraging clinical activity, with objective response rates of 30–40 % in the DeLLphi-301 trial. Novel combination approaches integrating BiTEs with checkpoint inhibitors or chemotherapy may further enhance efficacy. Beyond BiTEs, emerging immunotherapeutic strategies such as trispecific T-cell engagers (TiTEs), antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), and CAR-T/CAR-NK are reshaping the therapeutic landscape. Ongoing clinical trials are expected to define the role of these emerging therapies in optimizing survival and achieving durable disease control in relapsed SCLC.

Das kleinzellige Lungenkarzinom (SCLC) zählt zu den aggressivsten malignen Erkrankungen und ist gekennzeichnet durch hohe Rezidivraten mit einer äusserst ungünstigen Prognose, insbesondere im Bereich der Zweitlinientherapie. Trotz verfügbarer Optionen wie Topotecan und Lurbinectedin übersteigt das mediane Gesamtüberleben selten sechs Monate. Das chemotherapiefreie Intervall (CTFI) spielt eine entscheidende Rolle bei der Steuerung der Zweitlinientherapie, indem es die Patienten für eine erneute platinhaltige oder eine nicht-platinbasierte Behandlung spezifisch stratifiziert. Bispezifische T-Zell-Engager (BiTEs), darunter Tarlatamab, haben in der DeLLphi-301-Studie vielversprechende klinische Aktivität gezeigt, mit objektiven Ansprechraten von 30–40 %. Neuartige Kombinationsstrategien, die BiTEs mit Checkpoint-Inhibitoren oder Chemotherapie integrieren, könnten die Wirksamkeit weiter steigern. Über BiTEs hinaus entwickeln sich neue immuntherapeutische Ansätze wie trispezifische T-Zell-Engager (TiTEs), Antikörper-Wirkstoff-Konjugate (ADCs) sowie CAR-T/CAR-NK zunehmend das therapeutische Spektrum. Laufende klinische Studien werden voraussichtlich klären, inwieweit diese innovativen Therapien das Überleben optimieren und eine anhaltende Krankheitskontrolle bei rezidiviertem SCLC ermöglichen können.

Keywords: ES-SCLC, second-line, BiTE, immunotherapy, chemotherapy

Introduction

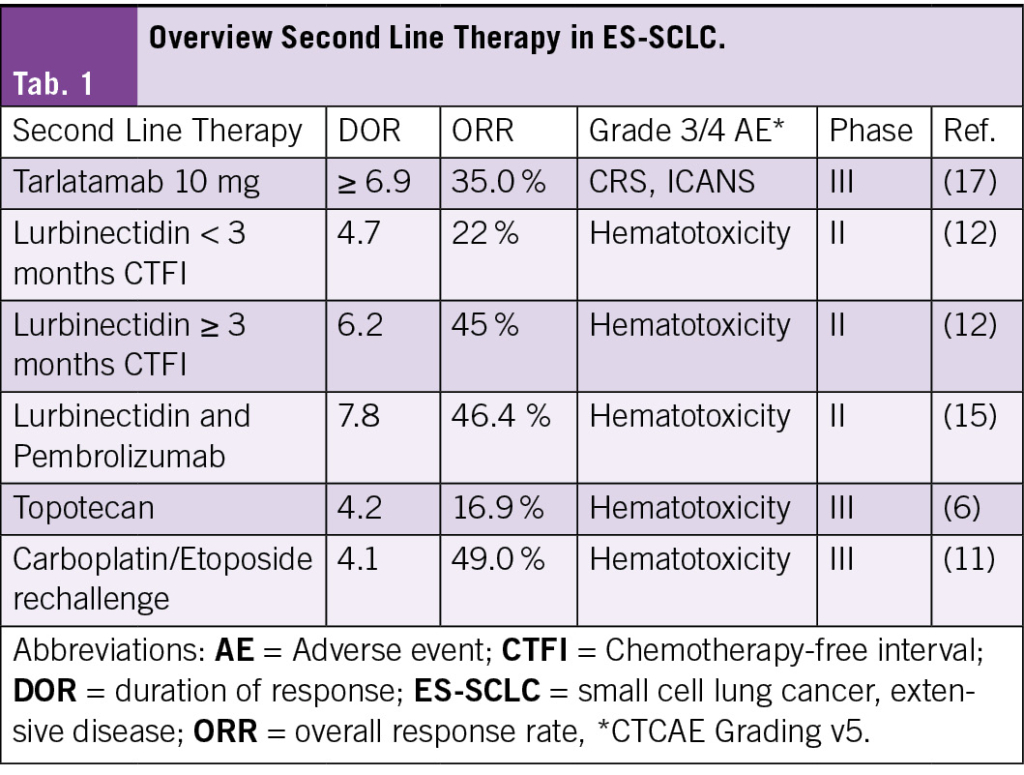

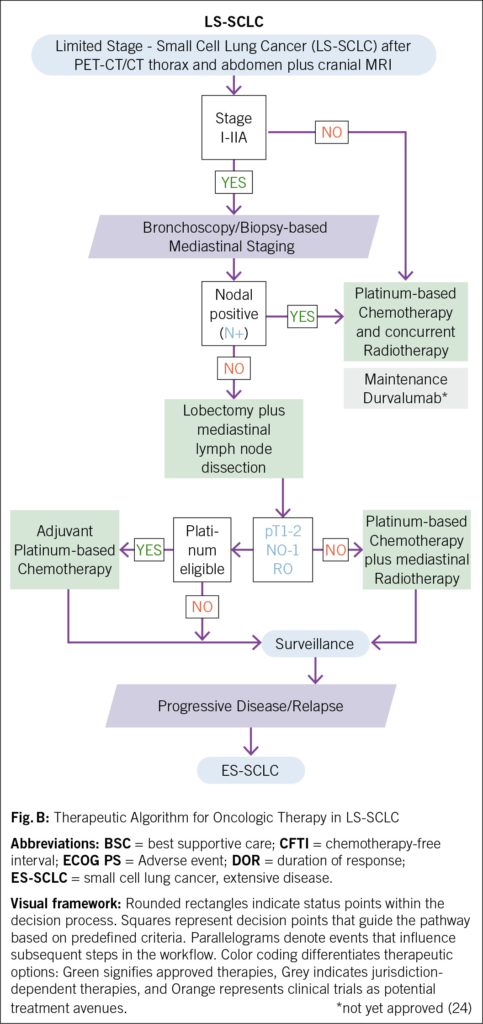

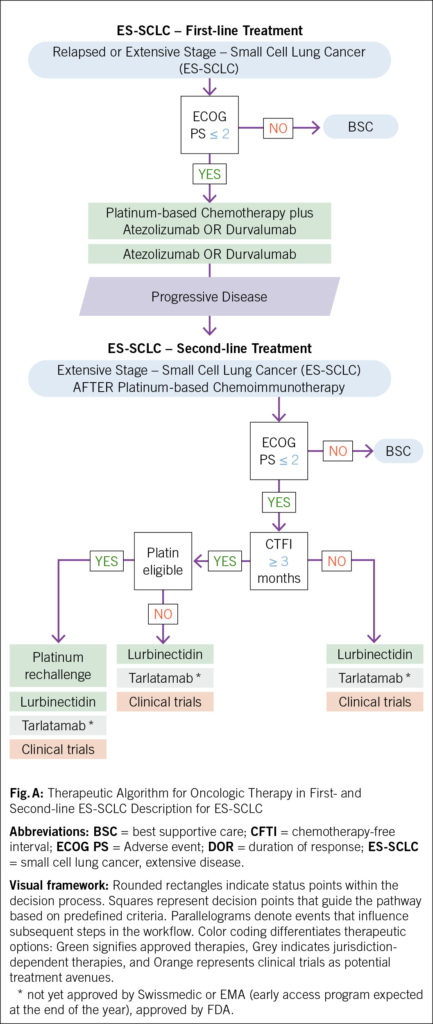

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is an aggressive malignancy with rapid growth and poor prognosis. Driven by a distinct molecular landscape, including a strong smoking-associated mutational signature with frequent tp53 and rb1 inactivation and an immunosuppressed tumor microenvironment (1), SCLC remains a challenging disease to treat. Approximately 70 % of patients are diagnosed with extensive-stage disease (ES-SCLC), and despite initial response to first-line chemoimmunotherapy, most experience disease progression within months (2, 3). In the second-line setting, median overall survival remains approximately six months (4–6): While topotecan has historically been the cornerstone of second-line therapy, its clinical efficacy remains limited. Other agents, such as lurbinectedin and immune checkpoint inhibitors, have demonstrated improved response rates but have failed to significantly extend survival. This review explores the evolving landscape of second-line therapy in ES-SCLC (Fig. A, Tab. 1) but not limited stage SCLC (Fig. B), with a focus on novel approaches, particularly Bispecific T-Cell Engager (BiTEs), which have shown promising results in recent clinical trials (4, 7).

Second-Line Treatment Options of ES-SCLC

For patients with ES-SCLC, progression following first-line chemoimmunotherapy with a platinum-based chemotherapy and one immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) (atezolizumab or durvalumab) is nearly inevitable within months (2, 3, 8). In the following oncologic strategy, second-line treatment decisions depend on factors such as the chemotherapy-free interval (CTFI), clinical features such as performance status/organ function, and prior treatments (Fig. A, Tab. 1). Given the historically poor prognosis of relapsed SCLC, participation in clinical trials for these patients is strongly recommended whenever possible (8, 9).

CTFI serves as a critical determinant of treatment selection. In patients with CTFI >3 months, where tumor chemosensitivity may persist, platinum-based doublet rechallenge is a preferred strategy, often recapturing transient disease control. For patients ineligible for platinum re-challenge, lurbinectedin, tarlatamab, or traditional cytotoxic agents such as topotecan and irinotecan represent viable options (9–12). For patients with CTFI ≤3 months, disease biology is typically defined by platinum resistance, necessitating a shift toward non-platinum regimens. Lurbinectedin, topotecan, irinotecan, and tarlatamab remain central to the therapeutic armamentarium, in addition to platinum rechallenge considered only in selected, platinum-sensitive patients with CTFI 6 months (9, 10, 12) (Fig. A, B). In ICI-naïve patients, immune checkpoint inhibitors (nivolumab or pembrolizumab) showed to be active in a minority of cases, but confirmatory trials have failed to show an overall survival benefit. In this population of patients, the LUPER trial demonstrated that indeed lurbinectedin combined with pembrolizumab achieved a 46.4 % objective response rate (ORR) with durable responses, particularly in platinum-sensitive SCLC patients, warranting further investigation (13–15). Beyond these, additional agents (paclitaxel, temozolomide, docetaxel, gemcitabine) and combination regimens such as cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine (CAV) may provide transient benefit in select cases (4, 6, 10).

Despite these options, treatment efficacy in second-line ES-SCLC remains poor, with median overall survival rarely exceeding six months. The use of BiTEs in the second-line setting offers now an emerging signal of progress in an otherwise stagnant field (4, 7).

Bispecific T-Cell Engagers

BiTEs, such as tarlatamab, obrixtamig (BI764532), and QLS31904, target delta-like ligand 3 (DLL3), an inhibitory Notch ligand expressed on most small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) tumor cells, while simultaneously engaging CD3 on T cells to promote cytotoxic immune responses. In the phase 2 DeLLphi-301 trial, 220 patients received tarlatamab after ≥2 prior lines of therapy, achieving objective response rates (ORRs) of approximately 30–40 %, with 59 % of responders maintaining their response for ≥ 6 months (7, 16). Building on these findings, the phase 3 DeLLphi-304 trial evaluated tarlatamab versus physician’s choice of chemotherapy (topotecan, lurbinectedin, or amrubicin) in 509 patients with SCLC progressing after first-line platinum-based therapy. Tarlatamab significantly prolonged overall survival (median 13.6 vs. 8.3 months; HR 0.60, 95 % CI 0.47–0.77; P< 0.001), and demonstrated a higher confirmed ORR (35 % vs. 20 %) and longer median duration of response (6.9 vs. 5.5 months) compared to chemotherapy. Cytokine-release syndrome (CRS), a known adverse event associated with BiTE therapy, was observed in 56 % of patients receiving tarlatamab, mostly during the first treatment cycle. The majority of CRS events were grade 1–2, with grade ≥ 3 CRS occurring in only 1 % of patients. ICANS occurred in 6 %, with one fatal case. Importantly, tarlatamab was associated with fewer grade ≥ 3 adverse events (54 % vs. 80 %), fewer treatment discontinuations due to toxicity (5 % vs. 12 %), and with greater reductions in dyspnea (−9.1 points; P< 0.001) and cough (odds ratio 2.04; P=0.01), and numerically higher scores for global health status and physical functioning than chemotherapy (17). The efficacy, favorable safety profile, and quality-of-life improvements highlight the clinical utility of tarlatamab and support its potential to become a new standard of care for both platinum-resistant and platinum-sensitive SCLC patients in the second-line setting; however, durable disease control remains challenging, as resistance to BiTEs may develop through mechanisms such as antigen loss, T-cell exhaustion, or tumor microenvironment adaptations. Resistance to BiTEs could arise through antigen loss, T-cell exhaustion, or tumor microenvironment adaptations, necessitating combination or sequential strategies to sustain efficacy. Future research may refine biomarker-driven patient selection, counteract resistance mechanisms such as antigen loss and T-cell exhaustion, and explore combination or sequential therapy strategies such as addition of Antibody-drug conjugates (ADC) to enhance treatment durability (4, 5, 18).

Future Perspectives

Advancing second-line treatment for ES-SCLC requires novel strategies such as tarlatamab and a precision approach. Combination approaches integrating BiTEs with checkpoint inhibitors, cytokine therapies, or chemotherapy could enhance efficacy and prolong responses. Molecular subclassification of SCLC may help identify optimal responders, improving treatment selection. Emerging ADCs for second-line ES-SCLC include sacituzumab govitecan (TROP2-targeting) (19), ZL-1310, which demonstrated an ORR of 74 % in a phase I trial, ABBV-011 (SEZ6-targeting), and B7-H3-directed agents such as ifinatamab deruxtecan, HS-20093, and ZL-1310, all under clinical investigation for their potential to improve outcomes in relapsed SCLC (18). Additionally, novel regimens targeting angiogenesis or vascular pathways—such as VEGF inhibitor ivonescimab, as well as the combination of benmelstobart plus anlotinib – are under evaluation to expand the therapeutic armamentarium in second-line (19, 20). Emerging immunotherapies, including TiTEs (trispecific T-cell engagers) such as HPN 328, CAR-T, and CAR-NK cells, are in early development and may offer innovative avenues for treatment (16, 22, 23). Ongoing research and clinical trials will determine how these emerging therapies integrate into the treatment landscape, potentially transforming outcomes for relapsed SCLC.

Abbreviation

ADC Antibody-Drug Conjugate

BiTE Bispecific T-Cell Engager

CAR-T Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy

CAR-NK Chimeric Antigen Receptor Natural Killer Cell Therapy

CD Cluster of Differentiation

CTFI Chemotherapy-Free Interval

CRS Cytokine-Release Syndrome

CT Computer tomogram

CTX Chemotherapy

DLL3 Delta-Like Ligand 3

ECOG PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status

EMA European Medicines Agency

ES-SCLC Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer

FDA Food and Drug Administration

ICI Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor

PET Positron emission tomogram

SCLC Small-Cell Lung Cancer

TiTEs Trispecific T-Cell Engagers

Copyright

Aerzteverlag medinfo AG

Clinic of Oncology, Cantonal Hospital Fribourg,

Fribourg, Switzerland

– Clinic of Oncology, Cantonal Hospital Fribourg,

Fribourg, Switzerland

– Faculty of Science and Medicine University of Fribourg,

Fribourg, Switzerland

Die Autorenschaft hat keine Interessenskonflikte im Zusammenhang mit diesem Artikel deklariert.

- Second-line treatment selection in ES-SCLC is guided by the chemotherapy-free interval (CTFI)

- BiTEs targeting DLL3 represent an emerging treatment option in second-line ES-SCLC, demonstrating durable responses with manageable toxicity and improvement of patient reported outcomes.

- Lurbinectedin in combination with pembrolizumab (LUPER trial) has shown promising efficacy.

- Future strategies will focus on overcoming resistance to BiTE therapy through biomarker-driven patient selection, combination approaches.

- CAR T cells are still under development.

- The evolving treatment landscape includes agents such as ADCs (sacituzumab govitecan, rovalpituzumab tesirine, and B7-H3-targeted therapies).

1. George J, Lim JS, Jang SJ, Cun Y, Ozretić L, Kong G, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiles of small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2015;524(7563):47–53.

2. Horn L, Mansfield AS, Szczęsna A, Havel L, Krzakowski M, Hochmair MJ, et al. First-Line Atezolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(23):2220–9.

3. Paz-Ares L, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, Reinmuth N, Hotta K, Trukhin D, et al. Durvalumab plus platinum–etoposide versus platinum–etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10212):1929–39.

4. Rudin CM, Brambilla E, Faivre-Finn C, Sage J. Small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2021;7(1):3.

5. Redin E, Quintanal-Villalonga Á, Rudin CM. Small cell lung cancer profiling: an updated synthesis of subtypes, vulnerabilities, and plasticity. Trends Cancer. 2024;10(10):935–46.

6. Pawel J von, Schiller JH, Shepherd FA, Fields SZ, Kleisbauer JP, Chrysson NG, et al. Topotecan Versus Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, and Vincristine for the Treatment of Recurrent Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(2):658–658.

7. Ahn MJ, Cho BC, Felip E, Korantzis I, Ohashi K, Majem M, et al. Tarlatamab for Patients with Previously Treated Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(22):2063–75.

8. Rossi A, Maio MD, Chiodini P, Rudd RM, Okamoto H, Skarlos DV, et al. Carboplatin- or Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy in First-Line Treatment of Small-Cell Lung Cancer: The COCIS Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1692–8.

9. Dingemans AMC, Früh M, Ardizzoni A, Besse B, Faivre-Finn C, Hendriks LE, et al. Small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up☆. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(7):839–53.

10. Ganti AKP, Loo BW, Bassetti M, Blakely C, Chiang A, D’Amico TA, et al. Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2021;19(12):1441–64.

11. Baize N, Monnet I, Greillier L, Geier M, Lena H, Janicot H, et al. Carboplatin plus etoposide versus topotecan as second-line treatment for patients with sensitive relapsed small-cell lung cancer: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(9):1224–33.

12. Trigo J, Subbiah V, Besse B, Moreno V, López R, Sala MA, et al. Lurbinectedin as second-line treatment for patients with small-cell lung cancer: a single-arm, open-label, phase 2 basket trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(5):645–54.

13. Spigel DR, Vicente D, Ciuleanu TE, Gettinger S, Peters S, Horn L, et al. Second-line nivolumab in relapsed small-cell lung cancer: CheckMate 331☆. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(5):631–41.

14. Marabelle A, Fakih M, Lopez J, Shah M, Shapira-Frommer R, Nakagawa K, et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(10):1353–65.

15. Calles A, Navarro A, Uribe BGDS, Colomé EÁ, Miguel M de, Álvarez R, et al. Lurbinectedin plus pembrolizumab in relapsed small cell lung cancer (SCLC): the phase I/II LUPER study. J Thorac Oncol. 2025;

16. Dolkar T, Gates C, Hao Z, Munker R. New developments in immunotherapy for SCLC. J Immunother Cancer. 2025;13(1):e009667.

17. Mountzios G, Sun L, Cho BC, Demirci U, Baka S, Gümüş M, et al. Tarlatamab in Small-Cell Lung Cancer after Platinum-Based Chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2025;

18. Meng Y, Wang X, Yang J, Zhu M, Yu M, Li L, et al. Antibody–drug conjugates treatment of small cell lung cancer: advances in clinical research. Discov Oncol. 2024;15(1):327.

19. Rudin CM, Pietanza MC, Bauer TM, Ready N, Morgensztern D, Glisson BS, et al. Rovalpituzumab tesirine, a DLL3-targeted antibody-drug conjugate, in recurrent small-cell lung cancer: a first-in-human, first-in-class, open-label, phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):42–51.

20. Cheng Y, Chen J, Zhang W, Xie C, Hu Q, Zhou N, et al. Benmelstobart, anlotinib and chemotherapy in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: a randomized phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 2024;30(10):2967–76.

21. Chen Z, Wu L, Wang Q, Yu Y, Liu X, Ma R, et al. Brief Report: Ivonescimab Combined With Etoposide Plus Carboplatin as First-Line Treatment for Extensive-Stage SCLC: Results of a Phase 1b Clinical Trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2025;20(2):233–9.

22. Molloy ME, Aaron WH, Barath M, Bush MC, Callihan EC, Carlin K, et al. HPN328, a Trispecific T Cell–Activating Protein Construct Targeting DLL3-Expressing Solid Tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2024;23(9):1294–304.

23. Jaspers JE, Khan JF, Godfrey WD, Lopez AV, Ciampricotti M, Rudin CM, et al. IL-18-secreting CAR T cells targeting DLL3 are highly effective in small cell lung cancer models. J Clin Investig. 2023;133(9):e166028.

24. Cheng Y, Spigel DR, Cho BC, Laktionov KK, Fang J, Chen Y, et al. Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Limited-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(14):1313–27.

info@onco-suisse

- Vol. 15

- Ausgabe 4

- Juli 2025