Einleitung

Der Verein Swiss Memory Clinics (SMC) engagiert sich – als Vertretung der Schweizerischen Behandlungszentren für Demenzerkrankungen und verwandte neurokognitive Störungen – seit vielen Jahren für eine qualitativ hochstehende und breit verfügbare Versorgung. Arbeitsgruppen bestehend aus Mitgliedern des SMC, der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Alterspsychiatrie und -psychotherapie (SGAP), der Schweizerischen Fachgesellschaft für Geriatrie (SFGG), der Schweizerischen Neurologischen Gesellschaft (SNG), der Schweizerischen Vereinigung der Neuropsychologinnen und Neuropsychologen (SVNP) und Expertinnen und Experten verschiedener Fachbereiche und Institutionen haben die vorliegenden Empfehlungen für die Diagnostik der Demenzerkrankungen, basierend auf der entsprechenden Publikation aus dem Jahre 2018 (1), vorbereitet. Diese aktualisierten Empfehlungen sollen den heutigen Stand der vorhandenen Diagnosemöglichkeiten abbilden, auf Entwicklungen in diesem Bereich hinweisen und die wichtigsten Instrumente der Diagnostik zusammenfassend vorstellen. Die Empfehlungen beschränken sich auf in der Schweiz zugelassene und verfügbare Diagnosemethoden. Detailliertere Ausführungen in den einzelnen Kapiteln sind unter https://www.swissmemoryclinics.ch/ sowie zusammengefasst unter https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/strategie-und-politik/nationale-gesundheitsstrategien/demenz/schwerpunktthemen/ambulantes-betreuungssetting.html zu finden. Besondere Anliegen der Expertengruppe sind, die Früh- und Differenzialdiagnostik der Demenzerkrankungen zu verbessern und einen für den klinischen Alltag nützlichen Wegweiser zur Verfügung zu stellen. In Ergänzung zu den hier vorgestellten Empfehlungen zur Diagnostik wurden kürzlich SMC-Empfehlungen zur Therapie der Demenzerkrankungen publiziert (2, 3).

Im vorliegenden Text wird darauf verzichtet, bei Personenbezeichnungen sowohl die männliche als auch die weibliche Form zu nennen. Die männliche Form gilt in allen Fällen, in denen dies nicht explizit ausgeschlossen wird, für beide Geschlechter.

Allgemeine Empfehlungen zum diagnostischen Prozess beim Hausarzt und in der Memory Clinic

Standard für den Hausarzt

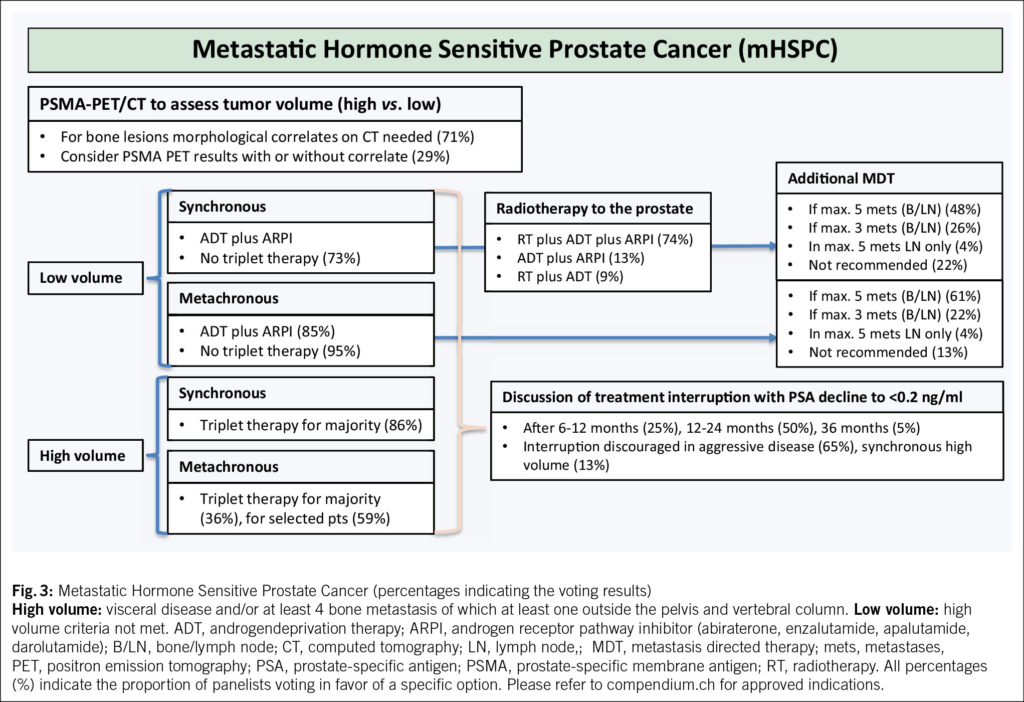

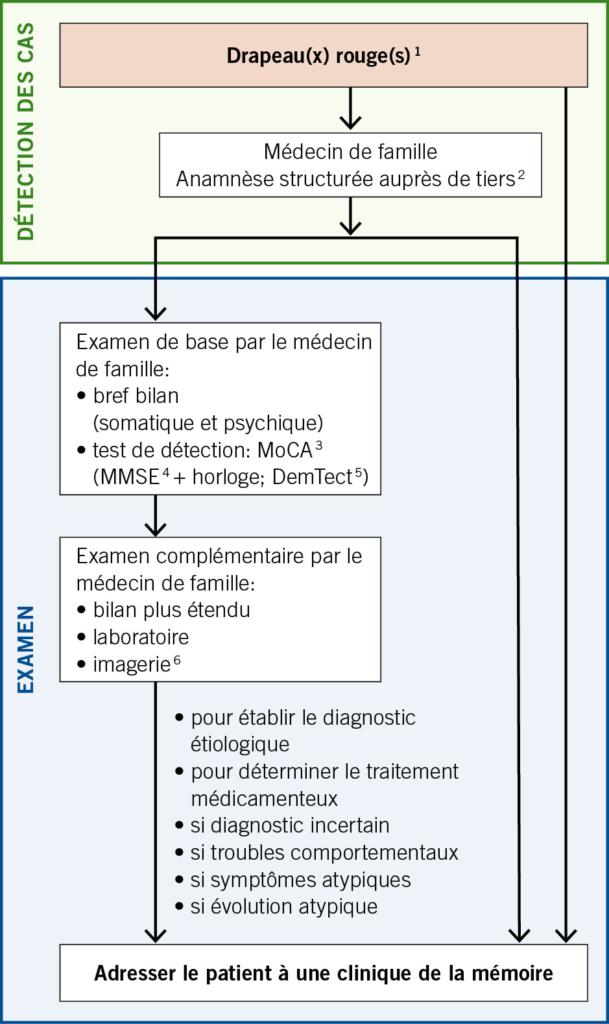

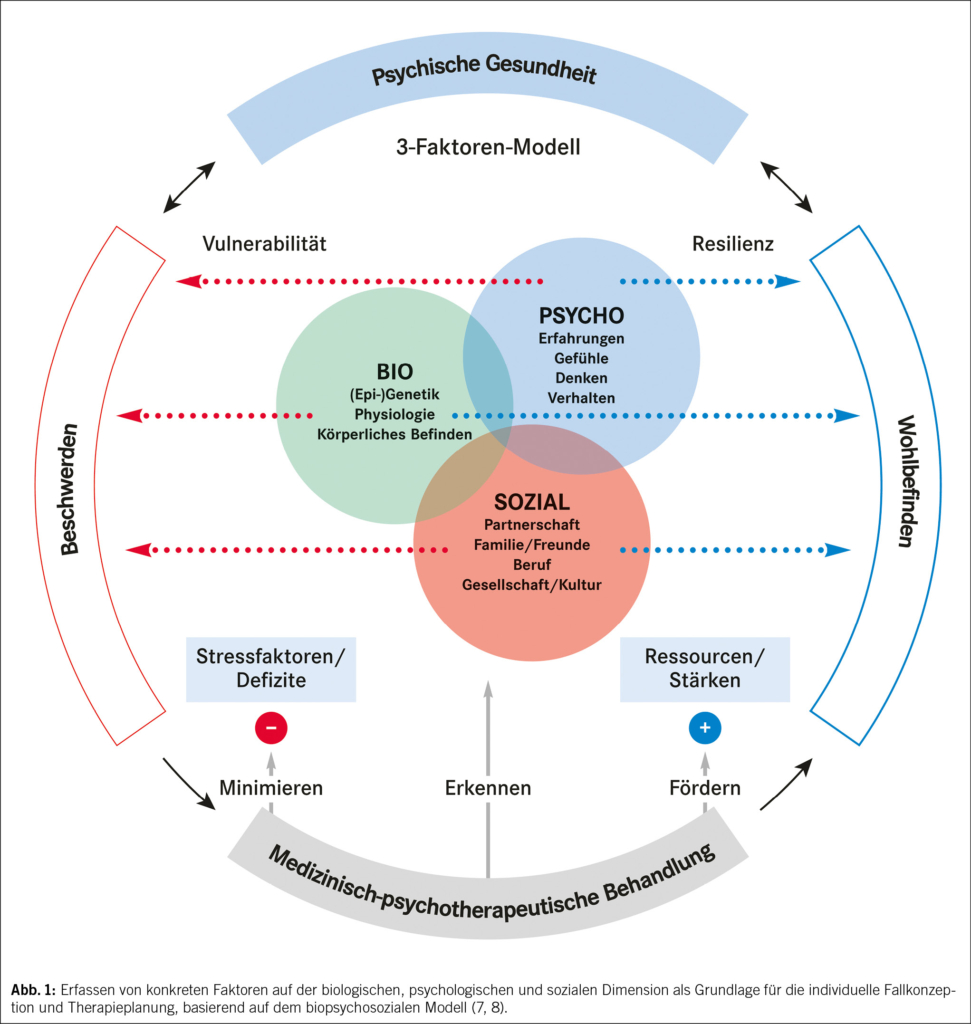

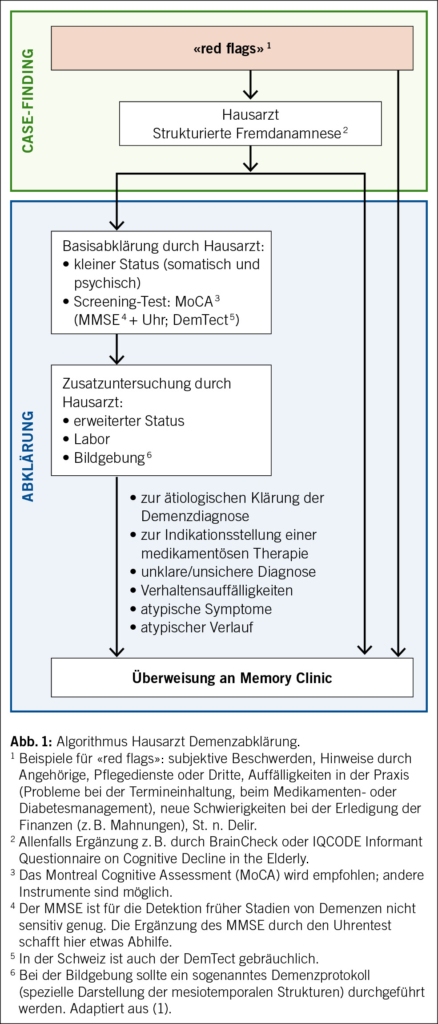

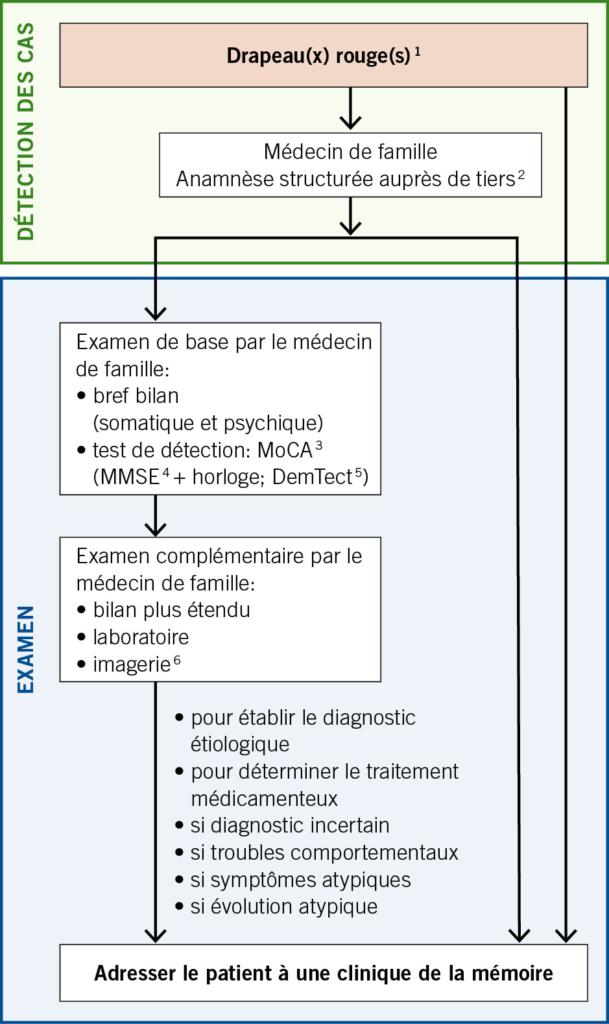

Aufgrund fehlender Evidenz für ein günstiges Kosten-Nutzen-Verhältnis im diagnostischen Prozess (4, 5) wird ein flächendeckendes Screening in höherem Alter nicht empfohlen. Stattdessen sollte ein sogenanntes «case finding» erfolgen. Mit «case finding» ist eine Strategie gemeint, die sich auf Individuen ausrichtet, bei denen Risikofaktoren oder Symptome einer möglichen Demenzerkrankung («red flags») vorhanden sind (4). Das gilt sowohl für Patienten im häuslichen Umfeld als auch für Patienten im Alters- und Pflegeheim. Die Erfassung von «red flags» ist eine Aufgabe der klinischen Grundversorgung (Abb. 1 mit empfohlenem Algorithmus). Je nach Situation kann die anschliessende Abklärung im hausärztlichen Setting oder an einer Memory Clinic erfolgen. Die Abklärung kann bei Bedarf auch anlässlich eines Haus- oder Heimbesuches, z. B. durch geriatrische oder alterspsychiatrische aufsuchende Dienste, erfolgen.

Bei der kognitiven Untersuchung in der Hausarztpraxis ist der Mini-Mental-Status-Examination(MMSE)-Test ein weit gebräuchliches Instrument (6). Die Ergänzung mit dem Uhrentest kann bessere Ergebnisse liefern (7). In der Schweiz ist auch der Demenz-Detektion-Test (DemTect) gebräuchlich (8). Aufgrund der höheren Sensitivität, der kostenlosen Verfügbarkeit in diversen Sprachen sowie der Bewährung im Alltag wird nun das Montreal-Cognitive-Assessment (MoCA) (9) generell für die Anwendung in der Praxis empfohlen.

Ablauf in der Memory Clinic

Interdisziplinäre Diagnostik durch einen Facharzt (Alterspsychiater, Geriater, Neurologe als Mitglieder des Memory-Clinic-Teams oder im Memory-Clinic-Netzwerk verfügbar) und Neuropsychologen:

• Ausführliche Eigen- und Fremdanamnese mittels semistandardisierten Interviews

• Psychiatrischer und somatischer Status

• Neuropsychologische Testung

• Bildgebung (Neuroradiologie, evtl. Nuklearmedizin)

• Laboruntersuchung (Blutentnahme, evtl. Lumbalpunktion)

• Diagnosestellung im Rahmen einer interdisziplinären Diagnosekonferenz mit Diagnosestellung nach ICD-10 oder DSM-5 (Kodierung gemäss ICD-10 oder künftig ICD-11)

• Diagnostische Einordnung der kognitiven Symptome nach Schweregrad sowie nach Präsenz behavioraler und psychischer Symptome der Demenz (BPSD)

• Der Schweregrad der kognitiven Störung wird unter Berücksichtigung der kognitiven Leistungseinbussen und der damit verbundenen Alltagsbeeinträchtigung bestimmt:

– Subjektive kognitive Störungen (kognitive Störung klinisch und neuropsychologisch nicht objektivierbar)

– Leichte kognitive Störung (mild cognitive impairment; minore neurokognitive Störung nach DSM-5)

– Demenz (majore neurokognitive Störung nach DSM-5)

– Leicht: Einschränkungen nur bei IADL (Instrumental Activities of Daily Living) (10), z. B. Haushalt, Umgang mit Geld

– Mittel: Einschränkungen auch bei BADL (Basic Activities of Daily Living) (11), z. B. Nahrungsaufnahme, Ankleiden

– Schwer: vollständige Abhängigkeit

• Stellungnahme zur Ätiologie der kognitiven Störung

• Diagnose- und Beratungsgespräch mit dem Patienten und ihm nahestehenden Personen, siehe unten

• Medikamentöse und nicht medikamentöse Behandlung, siehe Behandlungsempfehlungen der SMC (3)

• Die Memory Clinic ist im Krankheitsverlauf Ansprechpartnerin für verschiedene Fragestellungen wie klinisches Monitoring, Verlaufsdiagnostik und Anpassungen der Behandlungsmassnahmen sowie Durchführung und Vermittlung von Beratung und Begleitung etc.

Anamnese

Eine ausführliche Dokumentation und Beschreibung des prodromalen Verlaufs mit der Erfassung von Risikofaktoren, des Krankheitsbeginns und des weiteren Krankheitsverlaufs mit allfälligen Fluktuationen sind essenziell. Eine Familienanamnese mit Sterbealter und Todesursache der Eltern, der Geschwister und allenfalls der Kinder sollte erhoben werden. Falls Demenzerkrankungen in der Familie gehäuft vorkommen, sollten Angaben zum Alter bei Krankheitsbeginn und zum Verlauf festgehalten werden. Zudem wird eine vollständige persönliche Anamnese inklusive Medikamentenanamnese eingeholt.

Systemanamnese

• Noxen: Alkohol, Nikotin, Drogen, Missbrauch von Medikamenten

• Herzkreislauf: kardiopulmonale Beschwerden, Herzrhythmusstörungen (insbesondere Vorhofflimmern)

• Ernährung: Gewichtsverlauf, Nahrungsaufnahme inkl. Zahnstatus/Dysphagie, Verdauung, Defäkationsbeschwerden (z. B. Obstipation), Diäten, Diabetes

• Miktion: Urininkontinenz, Dysurie, häufiges Wasserlassen, Harndrang

• Sensationen: Schwindel, Kopfschmerzen, allgemeine Schmerzen

• Erholung: Tagesschläfrigkeit, Ein- und Durchschlafstörungen, (Alb-)Träume, nächtliche Unruhe, Parasomnien, Schnarchen, Apnoephasen

• Mobilität: Gehhilfen, Stürze (Häufigkeit, Ursache, Ablauf), subjektive Gangunsicherheit

• Neurologische Symptome: Koordinations- und Gleichgewichtsstörungen, Tremor, Tonus, allgemeine Schwäche (motorische und sensible Defizite), Augenmotilitätsstörungen, Dysphagie, Krampfanfälle

• Sprache: undeutliches Sprechen, Wortfindungsschwierigkeiten, Sprachverständnisstörung

• Sinnesorgane: Visus- und Hörverminderung, verändertes Riechen und Schmecken

• Psychische Verfassung: depressive Symptome inkl. Suizidalität, Angst, Reizbarkeit, Apathie, Agitation, Wahn, Sinnestäuschungen

• Deliranamnese

• Am Schluss: noch nicht angesprochene Beschwerden

Psychosoziale Anamnese

Die Demenzdiagnostik wird häufig bei älteren multimorbiden Patienten durchgeführt, bei denen die Kommunikationsfähigkeit und die Krankheitswahrnehmung beeinträchtigt und die Anamneseerhebung erschwert sein können.

In Form eines semistrukturierten Interviews wird mit den Betroffenen und den Angehörigen die eigentliche Problemanamnese zu erlebten und beobachteten Hirnleistungsstörungen im Alltag erhoben. Das erfolgt mit gezielten Fragen zu Gedächtnisleistungen, sprachlichen Fähigkeiten, zum Planungs- und Steuerungsverhalten, zur Kommunikation sowie zeitlichen und räumlichen Orientierungsfähigkeit. Angaben zur Alltagsgestaltung, insbesondere zum Grad der Selbständigkeit in den primären (basalen) und erweiterten (instrumentellen) Alltagsaktivitäten, werden detailliert erfragt. Dazu gehören Informationen zum Unterstützungsbedarf, zu den nötigen Hilfestellungen und bereits aktivierten Helfern. Es werden Informationen zum Autofahren (Fahrsicherheit, Fahrkompetenz) und/oder zur Benutzung öffentlicher Verkehrsmittel eingeholt. Zusätzlich empfiehlt es sich, Angaben zu sozialen Aktivitäten, Hobbys und gepflegten Kontakten zu erheben.

Das Interview wird ergänzt mit präzisen Fragen zur Händigkeit, zur primären und zu weiteren Sprachen sowie zu lebensgeschichtlichen Aspekten wie der Ausbildung und beruflichen Laufbahn, der familiären und aktuellen Lebenssituation. Ergänzt werden die medizinische und die psychosoziale Anamnese in der Regel durch Selbst- und Fremdbeurteilungsskalen, zum Beispiel:

• Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in

the Elderly (IQCODE)

• Nurses’ Observation Scale for Geriatric Patients (NOSGER)

• Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI)

• Neuropsychiatrisches Inventar (NPI)

• Geriatrische Depressionsskala (GDS)

• Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)

Erhebung der Alltagsfähigkeiten

Bei den Alltagsfähigkeiten (Activities of Daily Living, ADL) wird zwischen basalen (BADL) und instrumentellen Fähigkeiten (IADL) unterschieden. Die BADL umfassen die Bereiche Essen, Nahrungsaufnahme, Körperpflege, Ankleiden, Toilettengang, Kontinenz, die Fähigkeit, aus dem Bett oder von einem Stuhl aufzustehen, sowie Fortbewegung und Mobilität (mit oder ohne Gehhilfe). Zu den IADL werden folgende Kompetenzen gezählt: Mahlzeiten zubereiten, den Haushalt und die Wäsche erledigen, finanzielle Angelegenheiten erledigen, telefonieren, einkaufen, Medikamenteneinnahme, Fortbewegung unter Nutzung eines Transportmittels.

Die Erhebung der Alltagsfähigkeiten eines Patienten stützt sich im Rahmen der Anamnese und Fremdanamnese grundsätzlich auf vier mögliche Quellen:

1. Beobachtung des Patienten

2. Standardisierte Befragung des Patienten

3. Standardisierte Befragung der Angehörigen oder Betreuungspersonen

Erhebung bei aufsuchender Abklärung (Hausbesuch, im Heim etc.)

Dabei ist immer zwischen früher vorhandenen und aktuellen Fähigkeiten zu unterscheiden und besonders auf Diskrepanzen zwischen Eigen- und Fremdanamnese zu achten. Aufschlussreich kann auch die Frage sein, ob sich jemand neuerer Technologien (IADL) bedient oder lieber beim Altbewährten bleibt. Die strukturierte Erfassung der Alltagsfähigkeiten im Rahmen einer persönlichen, bei Bedarf vom Patienteninterview getrennt durchgeführten Fremdanamnese (12) ist zwingender Bestandteil jeder Demenzabklärung.

Eine aufsuchende Abklärung der ADL ist im Rahmen der Untersuchungen in der Memory Clinic meist aus praktischen Gründen nicht möglich. Diese kann z. B. durch aufsuchende Dienste oder Fachpersonen in einem separaten Schritt erfolgen.

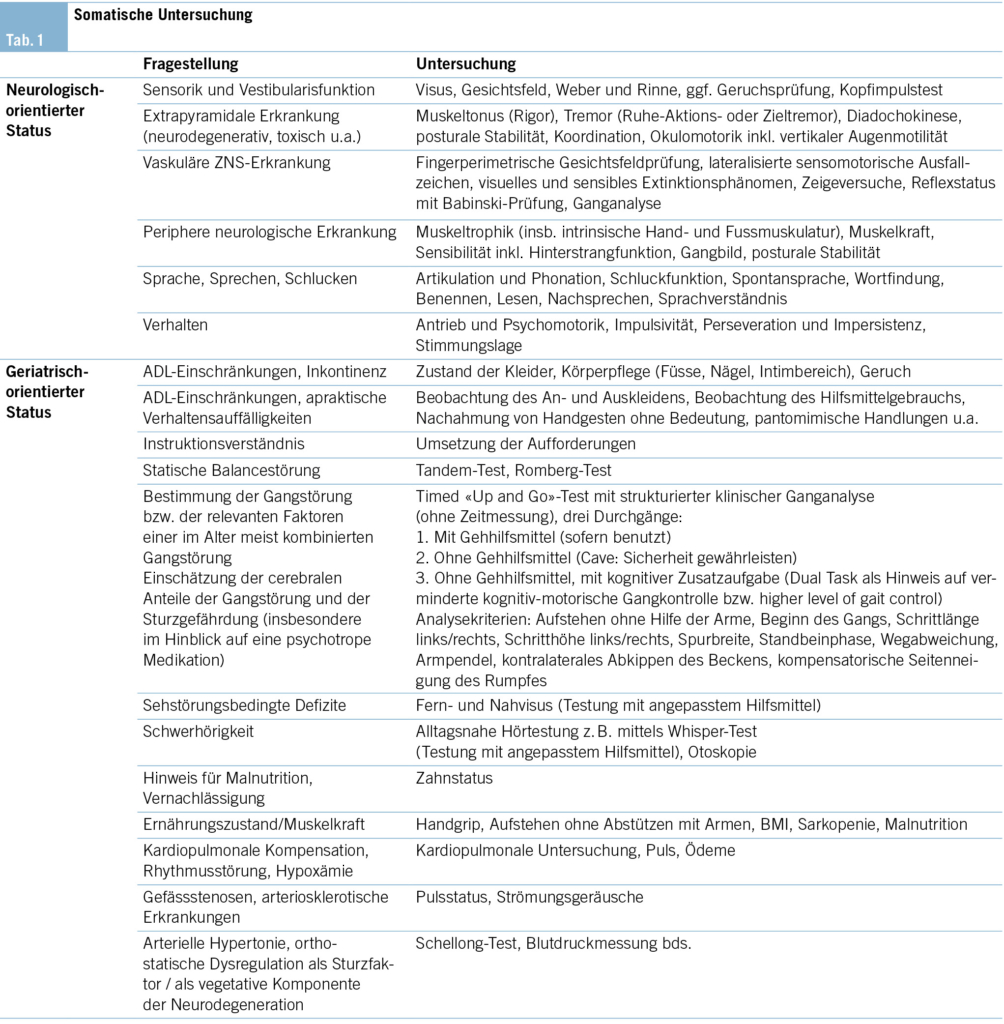

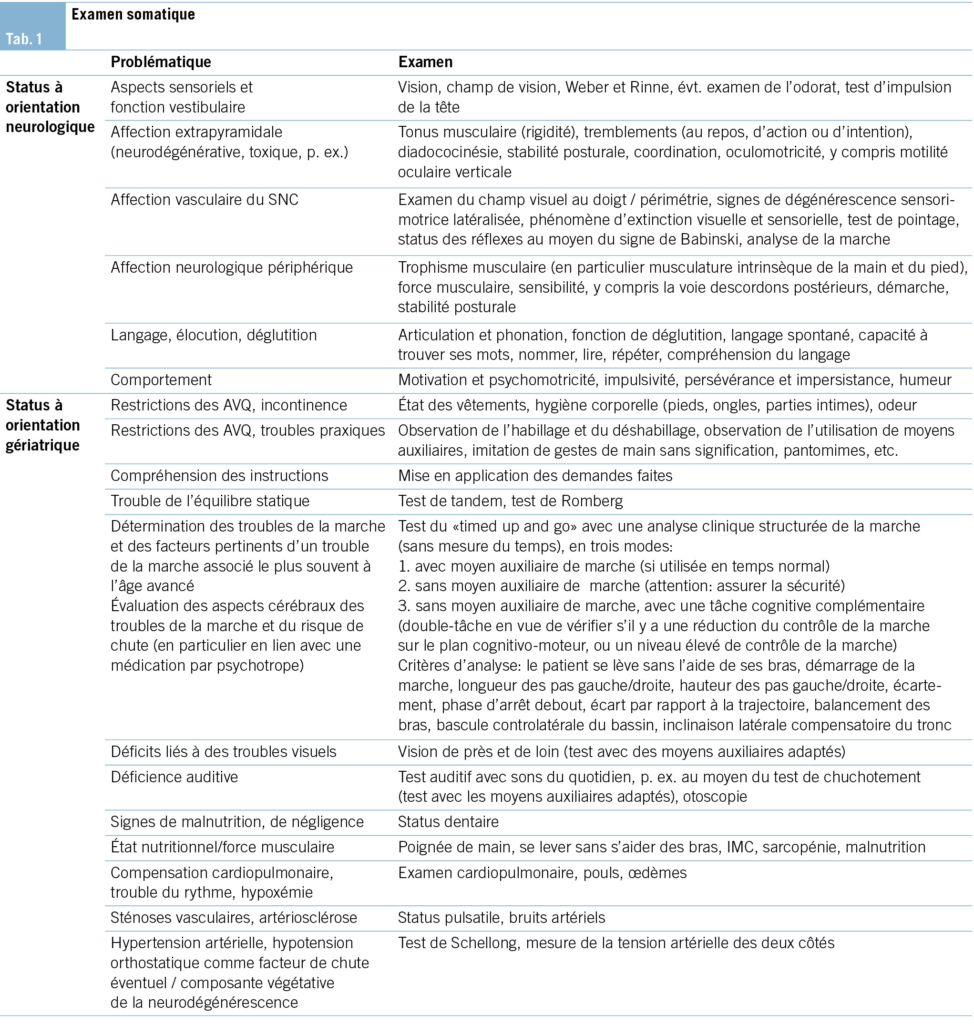

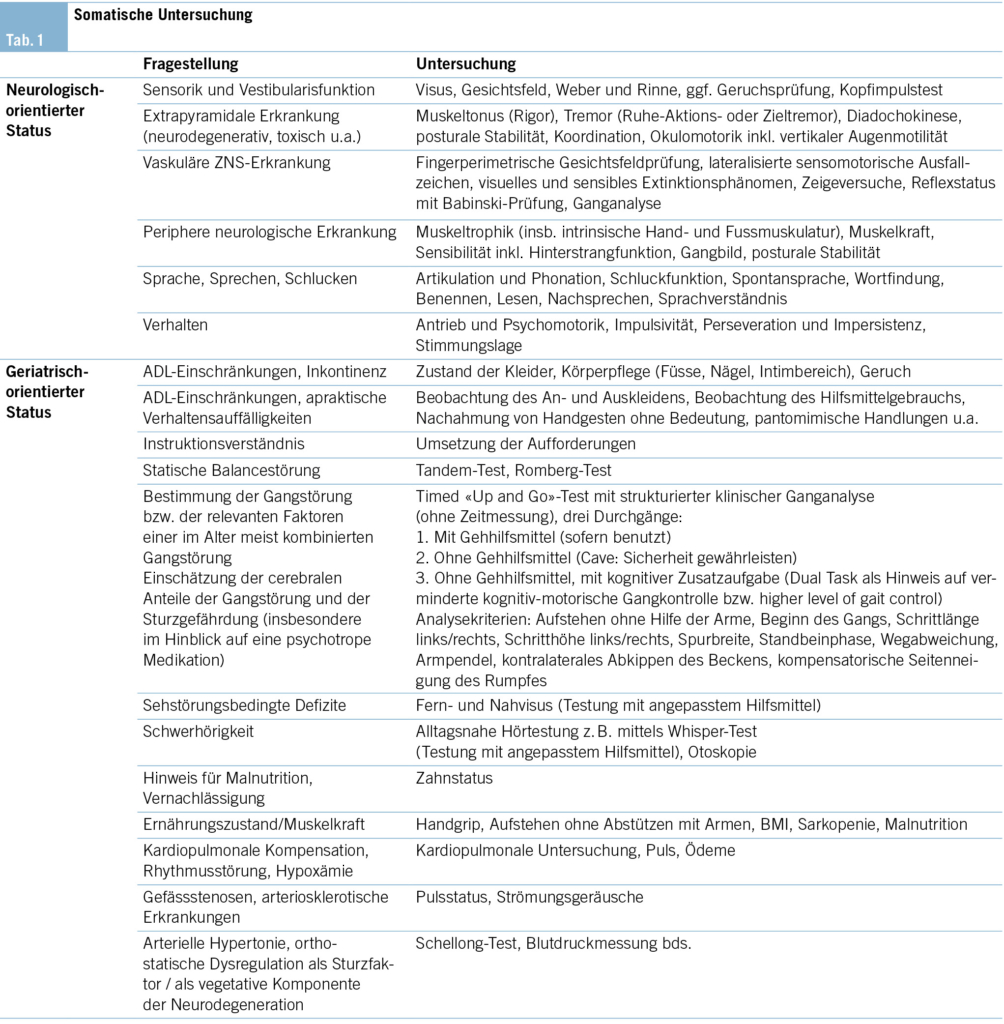

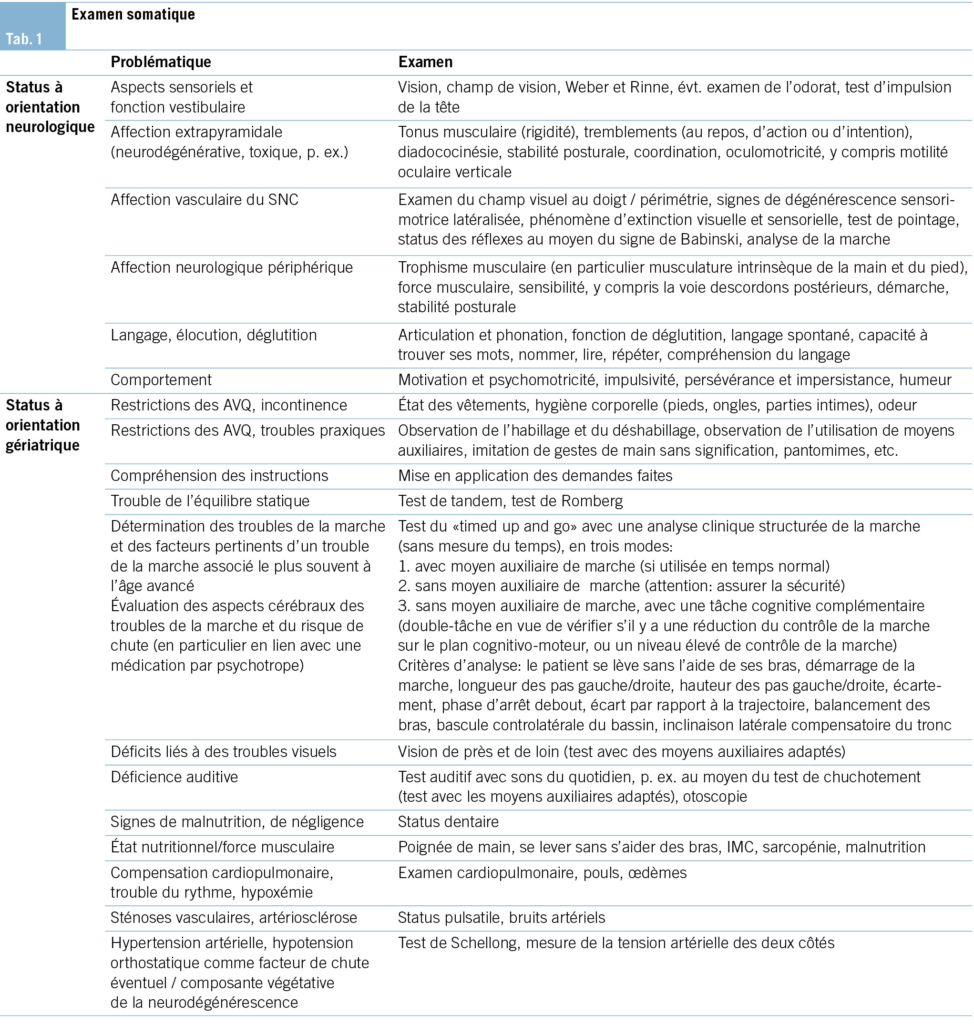

Somatische Untersuchung

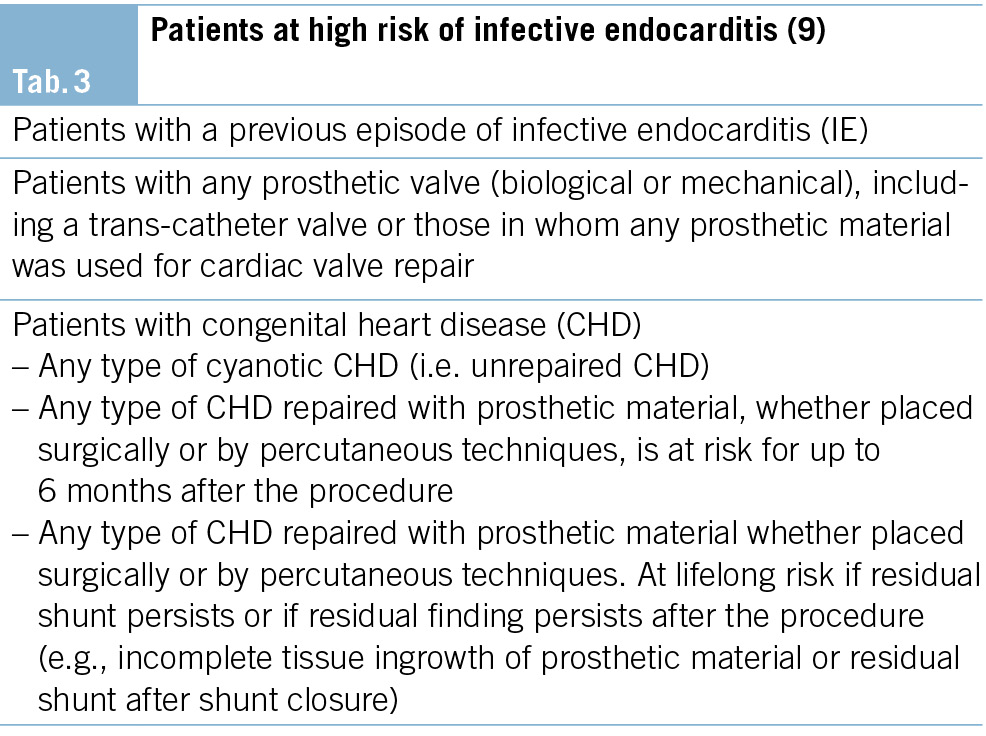

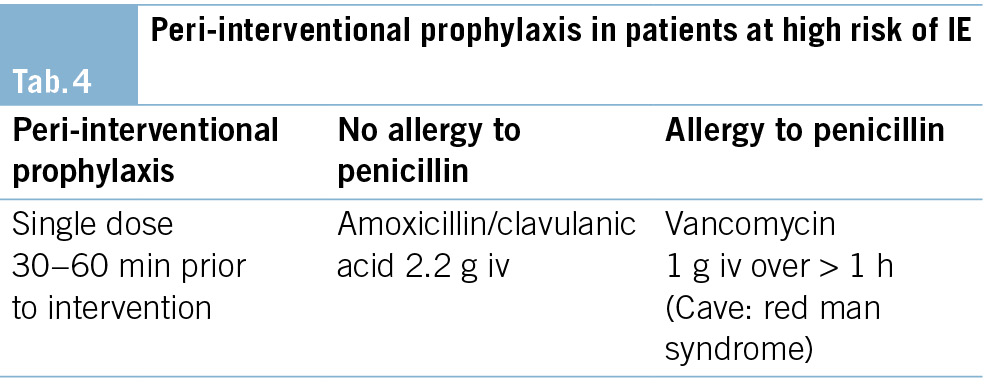

Die somatische Untersuchung richtet sich nach den Komorbiditäten und der Verdachtsdiagnose (Schwerpunkt der Fragestellung) und muss darauf entsprechend angepasst werden (Tab. 1).

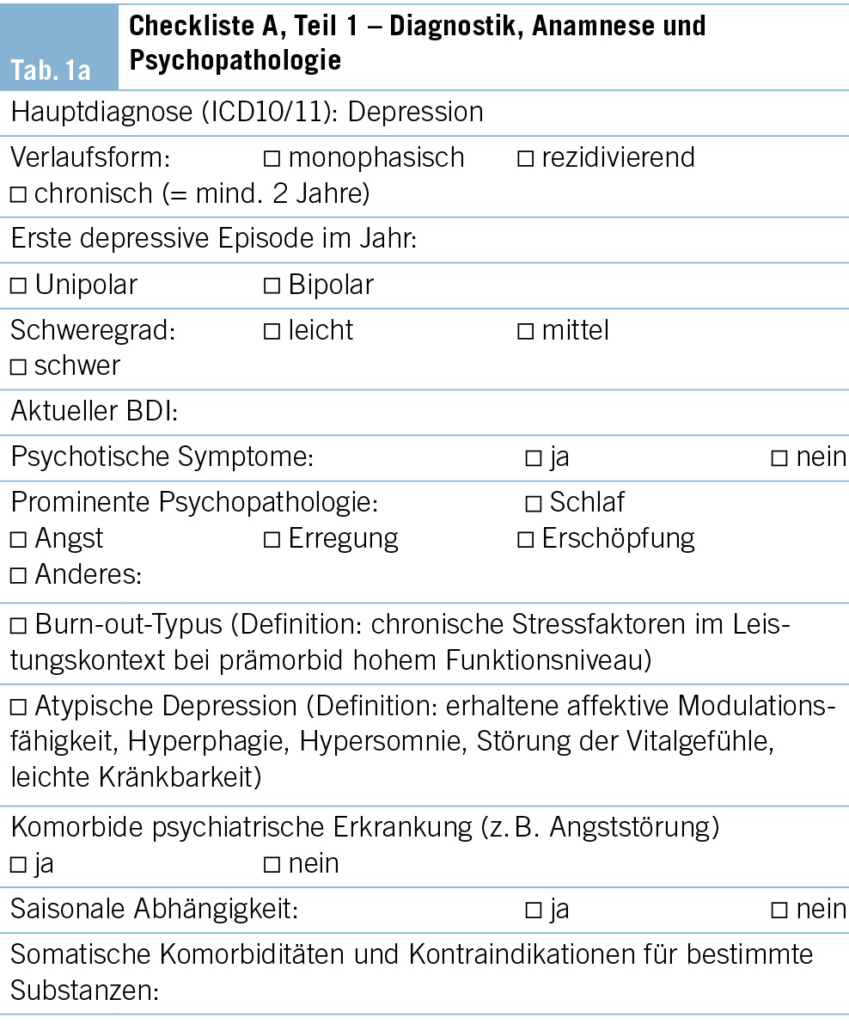

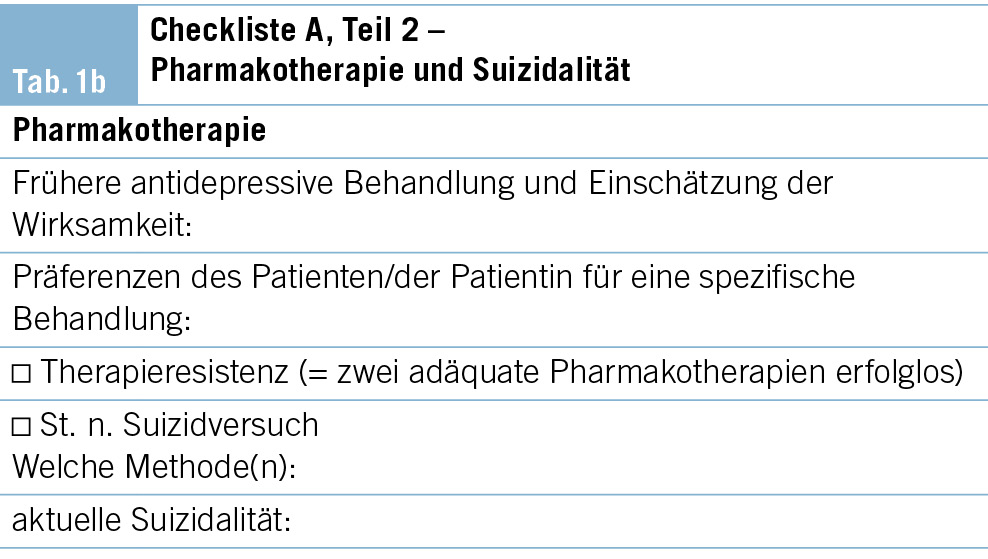

Psychopathologischer Status und behaviorale und psychische Symptome der Demenz (BPSD)

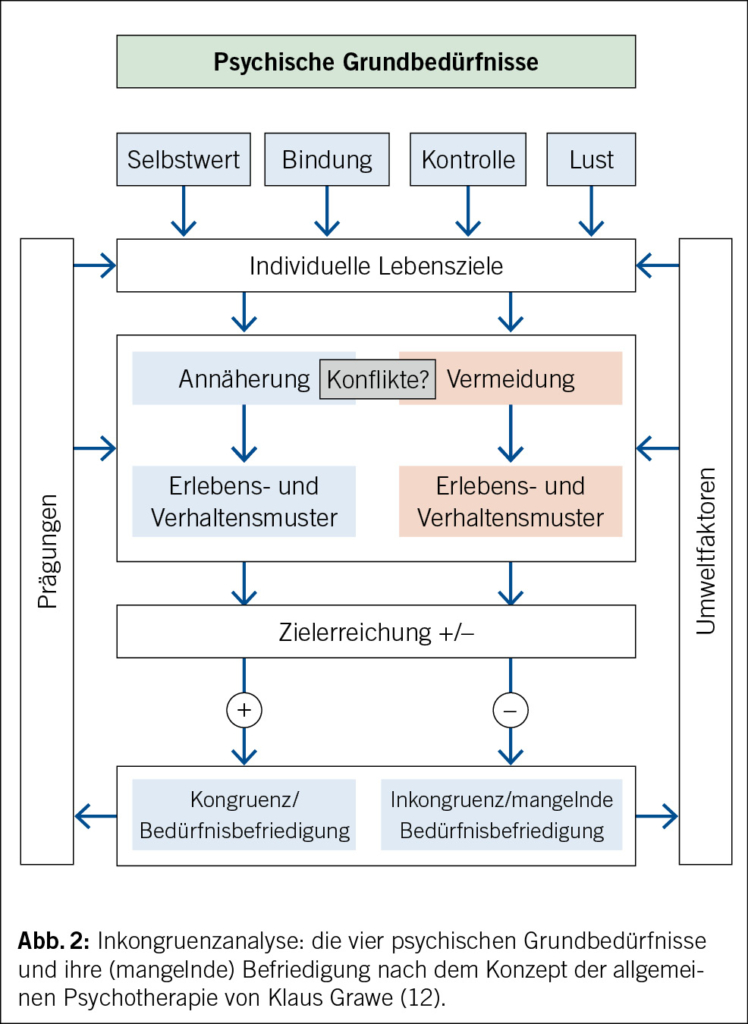

Nebst kognitiven Störungen und Einschränkungen bei Alltagsaktivitäten treten im Verlauf der Demenzerkrankungen oft verschiedene psychiatrische und Verhaltenssymptome auf, welche die Betroffenen erheblich beeinträchtigen und ihre Behandlung und Pflege erschweren können (13). Diese Symptome können auftreten als Ausdruck von psychischen Störungen, welche unabhängig von der Demenzerkrankung vorbestehen, oder als Symptome der Demenzerkrankung. Für neuropsychiatrische Symptome, die im Rahmen oder als Folge der Demenzerkrankung auftreten, wurde die Bezeichnung behaviorale und psychische Symptome der Demenz (BPSD) vorgeschlagen. Wesentlich für die Beurteilung und die Behandlung ist, sowohl biologische als auch psychologische und Umweltfaktoren zu berücksichtigen. Zu erwähnen ist, dass neuropsychiatrische Symptome nicht erst im Stadium der Demenz, sondern bereits bei MCI auftreten und sogar den kognitiven Störungen vorausgehen können (14, 15). Früh auftretende neuropsychiatrische Symptome sind mit einer schnelleren kognitiven und alltagsfunktionalen Verschlechterung assoziiert (16).

Standard

• Klinische Untersuchung auf das Vorliegen psychischer Symptome:

– Subjektive Bewertung durch den Patienten

– Fremdbewertung durch Angehörige oder Personen, die den Patienten gut kennen

– Psychopathologischer Grundstatus

– Beurteilung hinsichtlich des Vorliegens einer psychiatrischen Begleiterkrankung, insbesondere einer depressiven Störung oder eines Delirs

• Gewichtung der Informationen im Diagnoseprozess

• Berücksichtigung primärer psychiatrischer Begleiterkrankungen und neuropsychiatrischer Symptome/BPSD bei Therapievorschlägen zu kognitiven Störungen

• Überweisung an spezialisierte Sprechstunde, insbesondere bei mittelgradig bis schwer ausgeprägten psychiatrischen Symptomen, bei bestätigten oder vermuteten psychiatrischen Begleiterkrankungen, bei komplexen Implikationen für die Familie oder bei potenziell erforderlichen freiheitsbeschränkenden Massnahmen

Optional

• Die Anwendung eines psychopathologischen Beschreibungsrasters wird empfohlen (AMDP).

• Der Einsatz spezieller psychopathologischer Skalen wird empfohlen, z. B. das Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (17); bei V. a. Depression: Geriatrische Depressionsskala (18) oder Beck Depression Inventory (19) – wenn sich der Patient noch im Frühstadium der Demenzerkrankung befindet.

• Die Behandlung der psychischen Begleiterkrankungen an der Memory Clinic: je nach Kompetenz und Verfügbarkeit.

Neuropsychologische Untersuchung

Der wichtigste Beitrag der kognitiven Testung im Rahmen einer neuropsychologischen Abklärung sind die Früherkennung und Quantifizierung der beeinträchtigten kognitiven Dimensionen. Zudem liefert ein kognitives Stärken-Schwächen-Profil eine wichtige Grundlage für die individuelle Psychoedukation, Beratung und Therapie der Patienten und deren Angehörigen. In Anlehnung an die für neurokognitive Störungen differenzierte Darstellung im DSM-5 (20) muss die umfassende neuropsychologische Untersuchung qualitative und quantitative Aussagen zu folgenden sechs Dimensionen liefern:

• Komplexe Aufmerksamkeit: Daueraufmerksamkeit, geteilte Aufmerksamkeit, selektive Aufmerksamkeit, Verarbeitungsgeschwindigkeit

• Exekutive Funktionen: planen, entscheiden, Arbeitsgedächtnis, verwerten von Feedback/Fehlerkorrektur, handeln entgegen der Gewohnheit/Verhaltenshemmung, mentale Flexibilität

• Lernen und Gedächtnis: unmittelbares Gedächtnis, Kurzzeitgedächtnis (inkl. freier Abruf, Abruf mit Hinweisreizen, Wiedererkennen), Langzeitgedächtnis (semantisch, autobiografisch), implizites Lernen

• Sprache: Sprachproduktion (inkl. Benennen, Wortfindung, Wortflüssigkeit, Grammatik, Syntax), Sprachverständnis

• Perzeptiv-motorische Fähigkeiten: visuelle Wahrnehmung, Visuokonstruktion, perzeptuell-motorische Fähigkeiten, Praxis, Gnosis

• Soziale Kognition: Emotionen erkennen, Empathiefähigkeit, « theory of mind », Verhaltensänderungen

Die Beurteilung der Leistungen soll beruhen auf:

• der gemessenen Leistung (mindestens zwei Testverfahren pro Domäne, z. B. verbale und visuelle Gedächtnisleistung) in den Tests wie auch auf

• der Beobachtung/Befragung.

Mit Ausnahme der Dimension «soziale Kognition» (hierfür sind Instrumente derzeit noch in Entwicklung) existieren für alle Aspekte zeitlich ökonomisch einsetzbare kognitive Testinstrumente. Es sind Instrumente zu verwenden, die über eine Normierung verfügen, welche Alter, Geschlecht und Ausbildung der untersuchten Personen berücksichtigen.

Praktisches Vorgehen

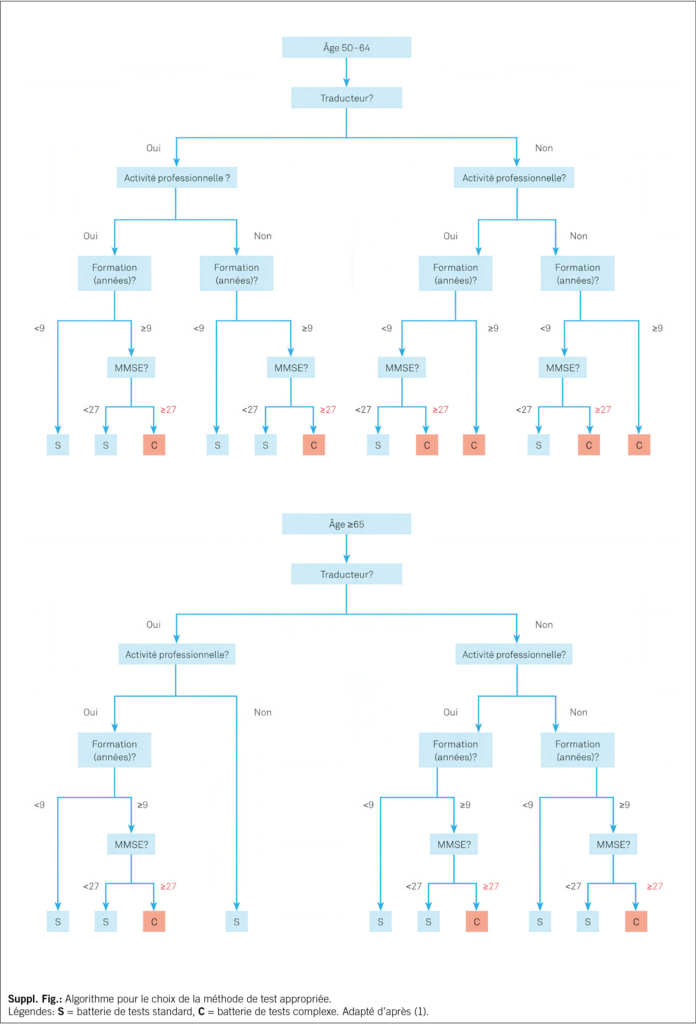

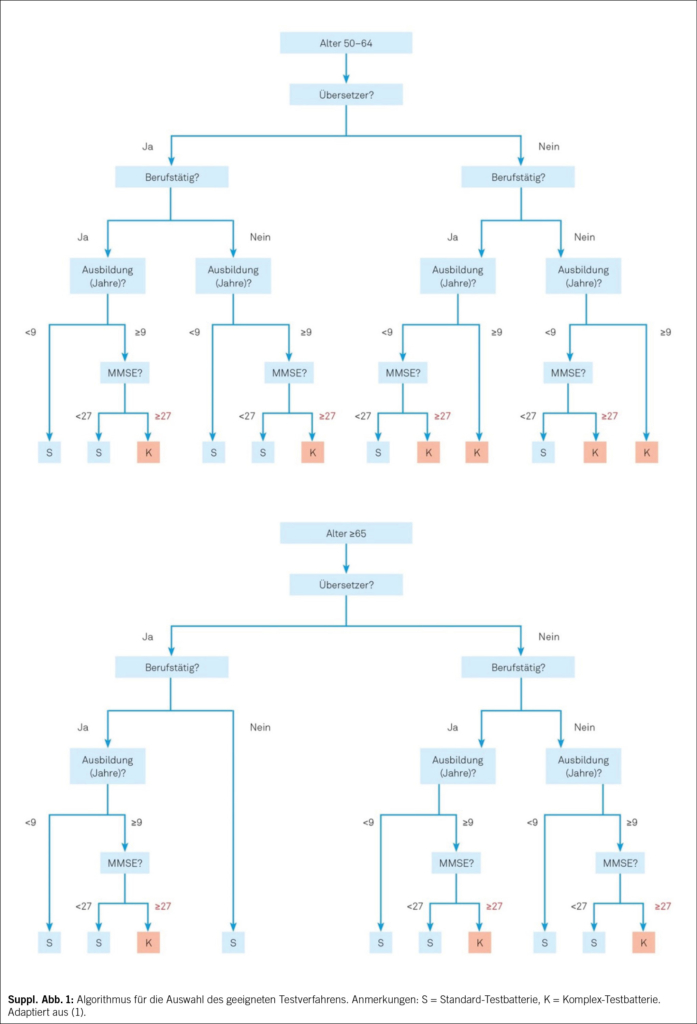

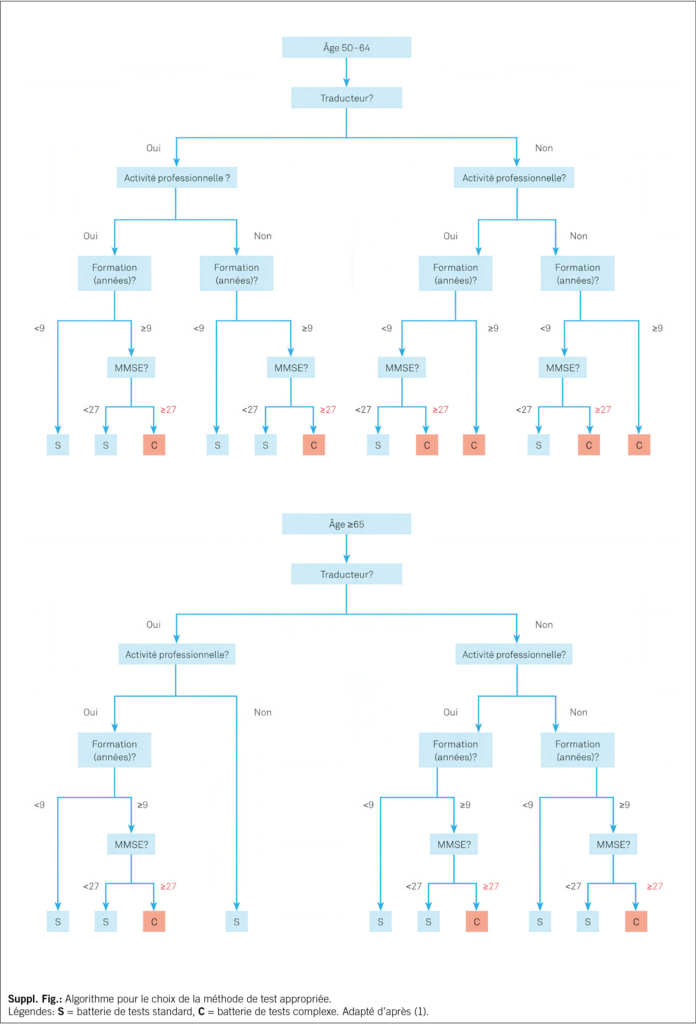

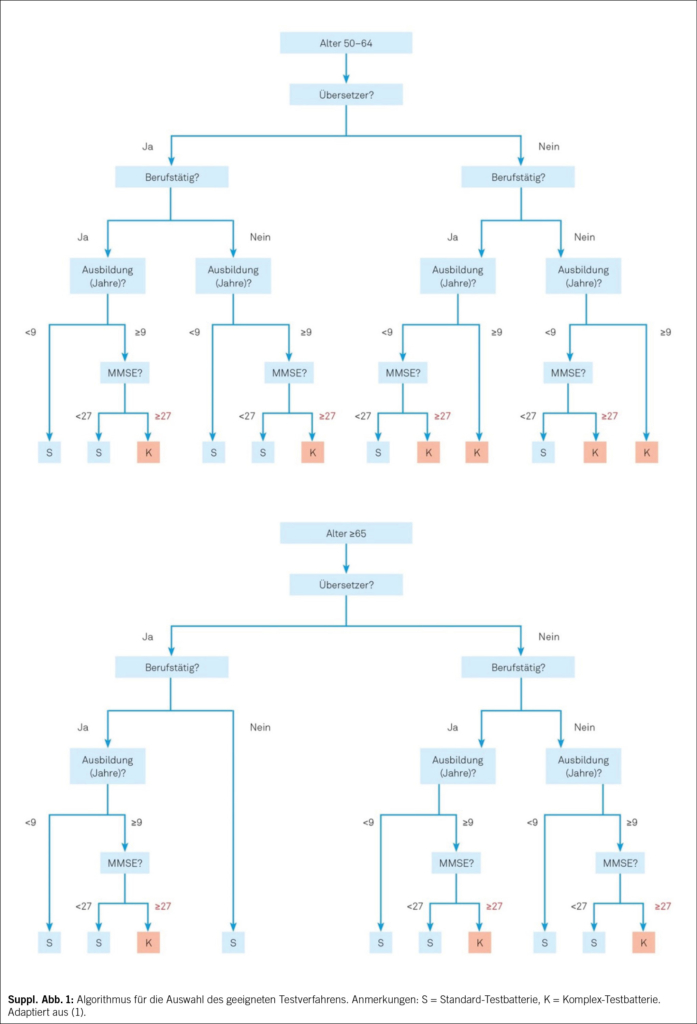

Zum etablierten Standard gehört die Durchführung eines kognitiven Kurztests, dessen Resultate unter Berücksichtigung der Informationen aus Anamnese, Fremdanamnese erlauben, die richtige Testauswahl für die umfassende hypothesengeleitete und personalisierte neuropsychologische Untersuchung zu treffen. MoCA (9) oder MMSE (6), kombiniert mit dem Uhrentest (7), wird als fester Bestandteil für das standardisierte Kurzverfahren empfohlen. Für Patienten mit fortgeschrittener Demenz kann sich eine differenzierte kognitive Testung erübrigen. Bei der Auswahl der geeigneten umfassenden kognitiven Testbatterie kann ein Algorithmus verwendet werden (Suppl. Abb. 1). Bei kognitiv nicht stark beeinträchtigten Patienten in einer Memory Clinic gehört die umfassendere neuropsychologische Untersuchung zum Standard. Eine in der deutschen Schweiz sehr gebräuchliche, bestens normierte und validierte Testbatterie ist die «Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease – Neuropsychological Assessment Battery (CERAD-NAB)», ergänzt mit Tests zur Untersuchung der Verarbeitungsgeschwindigkeit und Exekutivfunktionen, die als «CERAD-Plus» bezeichnet wird. Die Testunterlagen der CERAD-Plus inkl. der Möglichkeit zur Auswertung stehen Fachpersonen unter www.memoryclinic.ch kostenlos zur Verfügung. Eine ausführlichere Liste von Tests findet sich unter www.swissmemoryclinics.ch.

Eine solche Standarduntersuchung wird durch weitere neuropsychologische Testinstrumente ergänzt, wenn ein hohes kognitives Ausgangsniveau besteht, sich Fragen zum Beispiel zur Arbeitsfähigkeit stellen sowie bei seltenen Demenzformen mit spezifischen kognitiven Ausfallmustern.

Untersuchung spezieller Patientengruppen

Eine besondere Herausforderung stellen Patienten dar, die: (a) einen Migrationshintergrund mit eingeschränkter Sprachkompetenz in der Untersuchungssprache haben, (b) sensorische Einschränkungen haben, für welche in der Regel keine Normwerte existieren, (c) intellektuelle Entwicklungsstörungen haben, (d) Hochbegabung aufweisen oder (e) hochbetagt sind. Hier müssen die kognitive Untersuchung und Beurteilung auf die individuelle Situation angepasst werden, und es erfordert eine umfassende neuropsychologische Expertise. Darüber hinaus können somatische und psychiatrische Erkrankungen sowie eine die Kognition beeinträchtigende Medikation die Beurteilung erschweren und müssen in jedem Fall berücksichtigt werden.

Beurteilung und Interpretation

Die empfohlene Einteilung zum Schweregrad ist die sieben-kategorielle Klassifikation der «Leitlinien zur Klassifikation und Interpretation neuropsychologischer Testergebnisse» der Schweizerischen Vereinigung für Neuropsychologie (SVNP): https://neuro.psychologie.ch. Im Bericht über die neuropsychologische Untersuchung soll transparent sein, auf welche Art von Daten sich die Schlussfolgerungen beziehen. Zudem muss eine kurze Stellungnahme zum klinischen Eindruck erfolgen. Es ist sehr hilfreich, die Resultate der kognitiven Testung grafisch darzustellen. Es ist dann sinnvoll und erwünscht – gestützt auf die Resultate der kognitiven Testung und auf funktionell-neuroanatomischen Überlegungen –, Hypothesen zur Ätiologie einer vorhandenen Störung aufzustellen.

Labordiagnostik

Blutdiagnostik

Standard

• Blutbild, C-reaktives Protein

• Glukose

• Natrium, Kalium, Kalzium korrigiert

• Kreatinin, eGFR

• GOT (Glutamat-Oxalacetat-Transaminase), GPT (Glutamat-Pyruvat-Transaminase), γ-GT (Gamma-Glutamyl-Transferase)

• TSH (Thyreoidea-stimulierendes Hormon)

• Vitamin B12, Folsäure

• Cholesterin, HDL-Cholesterin, Triglyceride (Lipidstatus bei unter 80-Jährigen)

•

Ergänzende Untersuchungen bei spezifischem Verdacht oder pathologischen Resultaten der Standarddiagnostik:

• Vitamin D

• Lues- und Borrelienserologien, HIV-Test

• CDT (Carbohydrat-defizientes Transferrin)

• fT3, fT4, Parathormon, Kortisol

• Differenzialblutbild, BSG, INR

• CK (Creatinkinase), Harnstoff, Harnsäure, Bilirubin, Phosphat, Chlorid, Magnesium, Zink

• Blutzuckertagesprofil, HbA1c

• Vitamine B1 und B6, Niacin, Homocystein, Holotranscobolamin und/oder Methylmalonsäure

• Ferritin, Transferrin

• Kupfer, Coeruloplasmin, Urinstatus mit Kupfer-Clearance im 24-Stunden-Urin

• Noxenscreening (Blei, Quecksilber)

• Drogenscreening (z. B. Benzodiazepine)

• Drug-Monitoring

• Autoimmune und paraneoplastische Encephalitis-Antikörper

• Vaskulitisparameter

• APOE-Genotyp (z. B. im Rahmen der Forschung, bei geplanter Anti-Amyloid-Therapie mit monoklonalen Antikörpern)

Liquordiagnostik

Standard für folgende Indikationen (21): Ausschluss nicht primär degenerativer Demenzformen, hier insbesondere chronisch-entzündlicher ZNS-Erkrankungen:

• Bei rapid-progredienten, atypischen oder frühen (Erstmanifestation vor dem 65. Lebensjahr) Demenzerkrankungen

• Diagnostische- und Entlastungspunktion bei Verdacht auf Normaldruckhydrozephalus

• Unterstützende Diagnostik für den Nachweis von Neurodegeneration, Tau-Pathologie und/oder Amyloid-Pathologie; bei spezifisch gestellter Indikation und Aufklärung bei Verdacht auf Frühstadien der Alzheimer-Krankheit (einschliesslich des Stadiums der leichten kognitiven Störung, MCI)

Neben der Basisdiagnostik Liquor sollte bei Verdacht auf eine chronisch-entzündliche ZNS-Erkrankung eine zusätzliche Bestimmung der oligoklonalen Banden sowie gegebenenfalls Borrelien- und Lues-Serologien und weitere serologische Bestimmungen durchgeführt werden. Die Bestimmung von Beta-Amyloid (Aβ42, Aβ42/Aβ40), phosphoryliertes Tau (pTau) und Gesamt-Tau als Demenzbiomarker eignet sich als früh- und differenzialdiagnostisches Verfahren bei der Abklärung kognitiver Störungen und wird meist als Teil der Basisdiagnostik Liquor durchgeführt. Die obligatorische Krankenpflegeversicherung (OKP) übernimmt unter bestimmten Limitationen die Kosten für Analysen von Liquormarkern, auch bei Patienten mit MCI. Bei klinischem Verdacht auf Creutzfeldt-Jakob-Erkrankung können eine zusätzliche Bestimmung des Proteins 14-3-3 und eine RT-QuIC (Real-Time Quaking-Induced Conversion) im Liquor erfolgen. Eine individuell angepasste Aufklärung der Patienten zur geplanten Biomarkerdiagnostik und den möglichen Ergebnissen wird empfohlen (21).

Bildgebende Diagnostik

Neuroradiologische Verfahren

Die bildgebende Untersuchung des Gehirns im Rahmen der Diagnostik von Demenzerkrankungen erfüllt zwei wesentliche Funktionen:

1. Ausschluss von sekundären Demenzursachen, wie beispielsweise Raumforderungen, Liquorzirkulationsstörungen sowie vaskulär, metabolisch oder entzündlich bedingten Veränderungen

2. Beitrag zur ätiologischen Differenzierung und Zuordnung primärer Demenzerkrankungen

Die Bildgebung des Gehirns kann zur Diagnosestellung und Differenzialdiagnose zwischen der Alzheimer-Erkrankung und anderen, z. B. vaskulären oder frontotemporalen, Demenzen beitragen, wobei die differenzialdiagnostische Trennschärfe der strukturellen Bildgebung zwischen diesen Erkrankungen derzeit für die alleinige Anwendung nicht ausreichend ist (22). Ein wesentlicher Nutzen der strukturellen Bildgebung des Gehirns besteht in der Identifizierung und Beurteilung intrazerebraler Läsionen bezüglich Lokalisation und Quantität. Die Bildgebung ist dabei als ein Beitrag zur Gesamtbeurteilung und differenzialdiagnostischer Einordnung der demenziellen Krankheitsbilder in Verbindung mit Anamnese und den klinischen und neuropsychologischen und sonstigen Befunden anzusehen.

Standard

Die strukturelle Bildgebung mit kranialer Magnetresonanztomografie (MRT) – alternativ, bei Vorliegen von MRT-Kontraindikationen mittels kranialer Computertomografie (CT) – ist Teil der Standarddiagnostik.

Kraniale Magnetresonanztomografie (MRT)

Aufgrund der fehlenden Strahlenbelastung und des wesentlich besseren Gewebekontrastes im Gehirn im Vergleich zur CT sollte die MRT als Untersuchungsmethode der Wahl eingesetzt werden. Falls vorhanden, sollte ein 3- Tesla-MRT einem 1.5-Tesla-MRT vorgezogen werden. Die detaillierten Empfehlungen zum Untersuchungsprotokoll sind auf der SMC-Website zu finden (www.swissmemoryclinics.ch).

Kraniale Computertomografie (CT)

Bei fehlender Verfügbarkeit der MRT und bei Kontraindikationen für eine MRT (z. B. Herzschrittmacher, digital programmierte Implantate, ausgeprägte Klaustrophobie) sollte alternativ eine CT durchgeführt werden. Die CT ohne Kontrastmittel ist in der Regel ausreichend für den Nachweis oder Ausschluss von Raumforderungen, eines subduralen Hämatoms oder eines Hydrozephalus, mit Einschränkung auch für die Abklärung einer vaskulären Demenz.

Sonografie der hirnversorgenden Gefässe

Bei vaskulärer Demenz oder bei gemischt vaskulär-degenerativen Demenzformen kann die Beurteilung von Stenosen der hirnversorgenden Gefässe mittels Doppler- und Duplexsonografie relevant sein.

Nuklearmedizinische Verfahren

Positronen-Emissions-Tomografie (PET) mit 18F-Fluordesoxyglukose (FDG-PET)

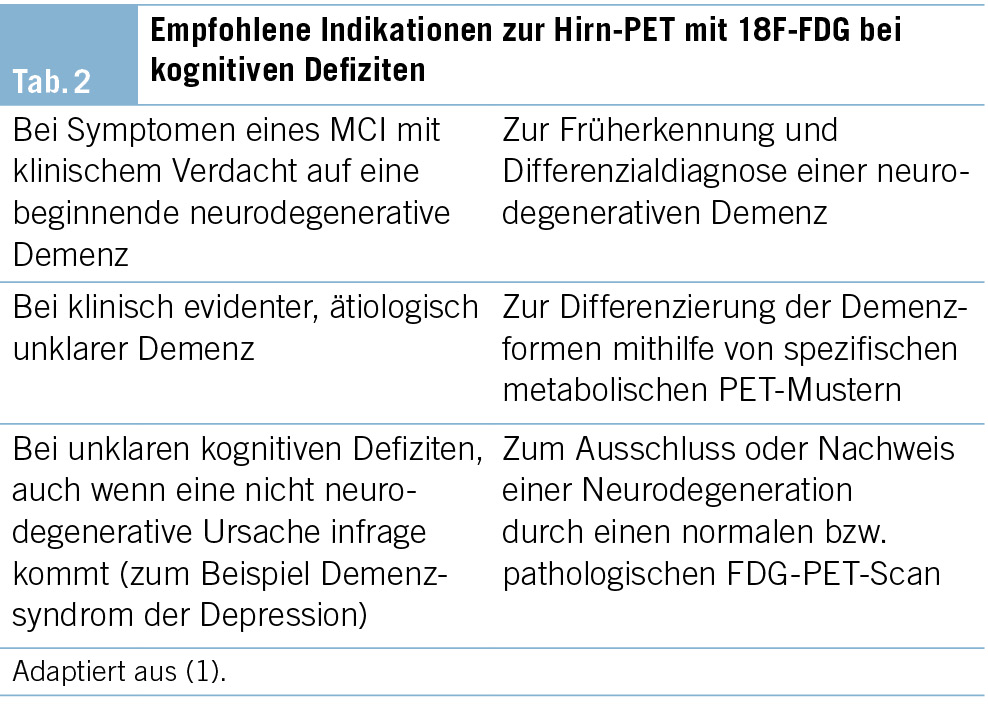

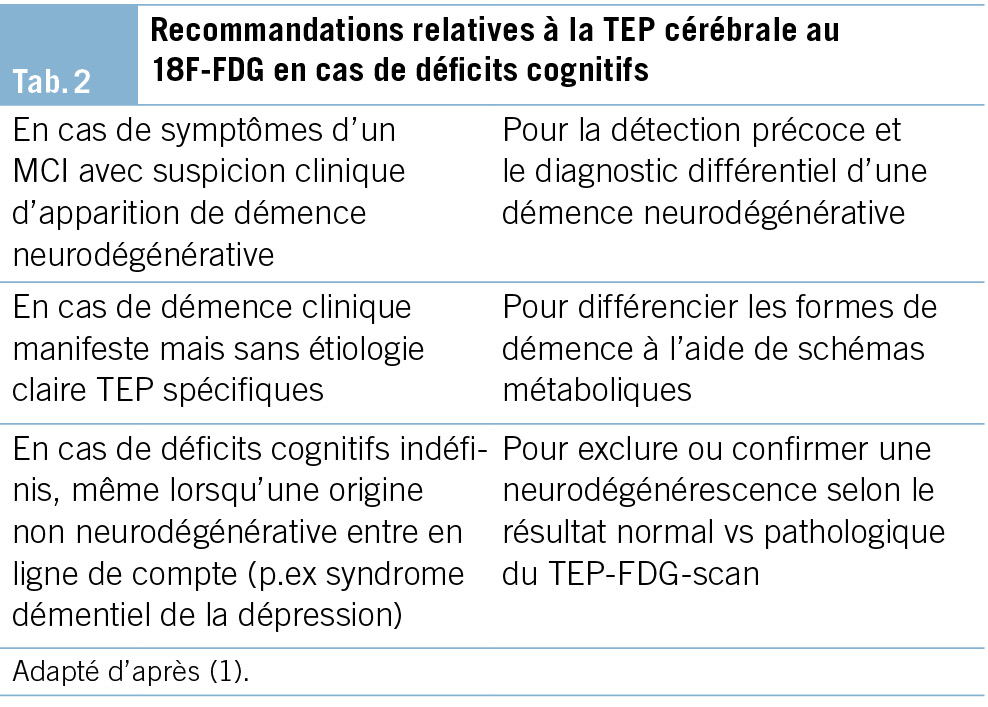

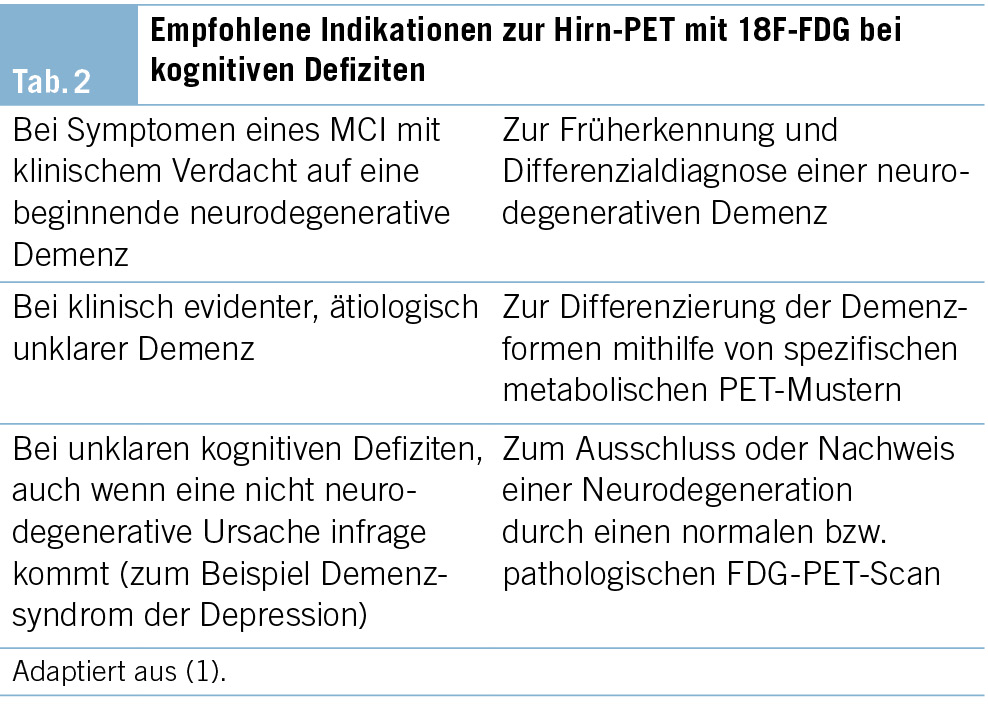

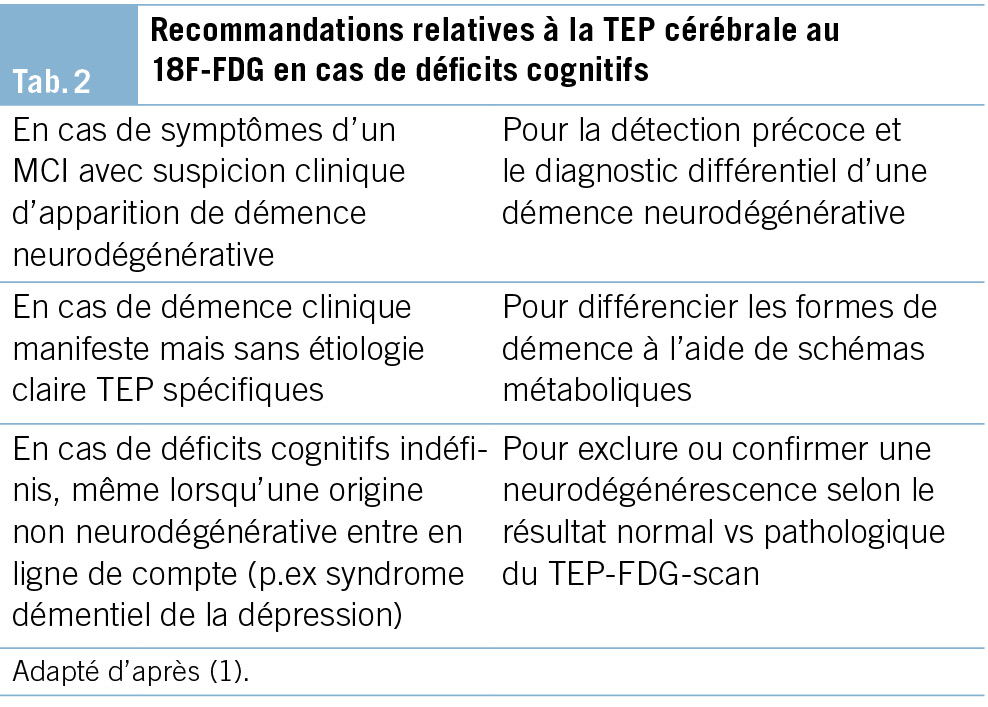

Die FDG-PET ermöglicht die bildliche Darstellung des regionalen Glukosemetabolismus des Gehirns und den Vergleich mit Normalwerten. Die FDG-PET ist die am besten validierte nuklearmedizinische Bildgebung zur Abklärung von Demenzen. Die empfohlenen Indikationen zur FDG-PET sind in der Tab. 2 aufgeführt.

Die FDG-PET weist eine hohe Sensitivität für den Nachweis funktioneller und neurodegenerativer Veränderungen der kortikalen Informationsverarbeitung auf und eignet sich hervorragend zur Frühdiagnostik, auch im Stadium einer leichten kognitiven Störung (MCI) (23). Die topische Zuordnung funktionsgestörter Areale ermöglicht zudem häufig die Differenzierung zwischen früher Neurodegeneration, funktionellen, demenzähnlichen Zuständen (z. B. bei psychiatrischen Erkrankungen) und kognitiven Beeinträchtigungen anderer Genese (z. B. limbische Enzephalitis).

Auch für eine Reihe weiterer, seltenerer neurodegenerativer Demenzen bestehen typische metabolische Muster, welche mittels der FDG-PET differenziert werden können. Dies betrifft die Demenz mit Lewy-Körperchen, verschiedene Formen der frontotemporalen Lobärdegenerationen, hier insbesondere die Varianten der primär progressiven Aphasie (semantische, nicht flüssige und logopenische), sowie die posteriore kortikale Atrophie (24).

Zusammenfassend wird die FDG-PET für die Diagnostik neurodegenerativer Demenzen als molekulare Bildgebungsmethode der ersten Wahl empfohlen (23). Für die Kostenübernahme gemäss Krankenpflege-Leistungsverordnung (KLV) sind Limitationen zu beachten.

Amyloid-PET

Die Amyloid-PET kann zuverlässig nachweisen, ob die Beta-Amyloid-Pathologie im Gehirn vorliegt oder nicht. Dabei können verschiedene Tracer eingesetzt werden, die an Amyloid-Plaques binden. Seit 01.04.2020 besteht eine Leistungspflicht der Krankenkassen für Amyloid-PET (Limitationen sind zu beachten) als weiterführende Untersuchung in unklaren Fällen nach inkonklusiver Liquordiagnostik oder wenn eine Lumbalpunktion nicht möglich oder kontraindiziert ist (23).

Bei künftig erwarteter Verfügbarkeit neuer Arzneimittel, die sich gegen Amyloid-Pathologie richten, zeichnet sich ein erweitertes klinisches Einsatzgebiet ab.

Bildgebung des dopaminergen Systems: Dopamin-Transporter-SPECT mit 123I-Ioflupane und 18F-DOPA-PET

Bei der Dopamin-Transporter-SPECT mit 123I-Ioflupane und der PET mit 18Fluoro-DOPA handelt es sich um eine nuklearmedizinische Untersuchung, um die zerebrale Dopamin-Verfügbarkeit zu bestimmen (25). Der Nachweis eines striatalen dopaminergen Defizits durch diese Verfahren kann zuverlässig zwischen einer DLB (mit pathologischem Befund im Striatum) und Demenzen ohne Lewy-Körperchen unterscheiden (26). Für zwei SPECT-Radiopharmaka (DaTSCAN® und Striascan®) sowie für 18F-DOPA-PET wurde die Swissmedic-Zulassung für diese Indikation erteilt.

Genetische Untersuchung

Eine häufig von Betroffenen von Demenzerkrankungen und ihren Angehörigen gestellte Frage ist, ob die Erkrankungen, die sie betreffen, vererbt werden. Die Mitarbeiter einer Memory Clinic müssen in der Lage sein,

• Fälle der familiär auftretenden Demenzerkrankungen zu identifizieren;

• Informationen im Rahmen der Diagnosestellung zu gewichten;

• die Indikation für eine genetische Beratung zu stellen;

• Aufklärung und Beratung zu genetischen Risikofaktoren für die häufigsten Demenzerkrankungen zu leisten;

• den Patienten bzw. dessen Familie an ein humangenetisches Institut zu verweisen (meist an eine Universitätsklinik angeschlossen). Überweisungen sind insbesondere in folgenden Fällen indiziert:

– ein Angehöriger ersten Grades mit möglicher Erkrankung, Alter unter 50 Jahre

– zwei Angehörige ersten Grades mit möglicher Erkrankung, Alter unter 60 Jahre

Weitere Untersuchungsverfahren

Basierend auf Anamnese oder auf Befunden im somatischen Status kommen weitere Untersuchungen als Ergänzung in Betracht.

Elektroenzephalografie (EEG)

Eine EEG-Untersuchung kann nützliche Informationen liefern bei:

• erheblichen Schwankungen von Vigilanz und Orientierung zum Ausschluss einer epileptischen Genese

• bei V. a. entzündlich-infektiöse, entzündlich-autoimmune oder metabolische ZNS-Erkrankungen (e. g. limbische Encephalitis, Hashimoto-Encephalopathie) sowie bei V. a. Creutzfeldt-Jakob-Erkrankung

Schlafdiagnostik

Demenzerkrankungen gehen häufig mit einem erhöhten Schlafbedürfnis, d. h. einem verlängerten Nachtschlaf und einer erhöhten Tagesschläfrigkeit, einher. Schlafassoziierte Atemstörungen können, ebenso wie hirnorganische Erkrankungen, die Schlafarchitektur stören und eine exzessive Tagesschläfrigkeit sowie Einschränkungen von Aufmerksamkeitsleistungen verursachen. Sie stellen einen unabhängigen Risikofaktor für kardio- und zerebrovaskuläre Ereignisse dar und sind häufig behandelbar.

Eine exzessive Tagesschläfrigkeit kann einfach mit dem Epworth-Sleepiness-Fragebogen (27) abgeschätzt werden. Die Durchführung einer apparativen schlafbegleitenden Untersuchung (Aktimetrie, nächtliche Pulsoximetrie, Polygrafie, Polysomnografie) kann indiziert sein bei:

• einer exzessiven Tagesschläfrigkeit und Zeichen einer nächtlichen Atemstörung zum Ausschluss eines Schlaf-Apnoe-Syndroms

• V.a. REM-Schlaf-Verhaltensauffälligkeiten

• V.a. schlafgebundene epileptische Anfälle

Geruchstestung

Eine Geruchstestung kann bei der Frühdiagnostik der Verdachtsdiagnose Alzheimer-Demenz unterstützende Befunde liefern. Bei der Alzheimer- sowie bei der Parkinson-Krankheit kommt es frühzeitig zu einer Beeinträchtigung der Geruchsleistung. Es stehen verschiedene validierte Tests zur Verfügung.

Ganganalyse

Neurodegenerative Erkrankungen können neben der Kognition auch motorische Funktionen beeinträchtigen. Menschen mit einer demenziellen Erkrankung haben gegenüber gleichaltrig Gesunden früh ein erhöhtes Sturzrisiko. Eine strukturierte klinische Ganganalyse ermöglicht hier eine Bewertung der Gangsicherheit bzw. der Sturzgefährdung. Sie hilft, die Indikation für geeignete therapeutische und präventive Massnahmen (Training, Gehhilfsmittel u. a.) zu stellen. Für eine quantitativ ausgerichtete Ganganalyse stehen validierte klinische Mobilitätstests (e. g. Timed «Up and Go»-Test), aber auch computerisierte Verfahren (Bewegungsdaten werden digital erfasst, z. B. über Drucksensoren auf einem Laufteppich) zur Verfügung.

Okulomotorik-/Gesichtsfelduntersuchung

Der klinischen Untersuchung der Okulomotorik und des Gesichtsfeldes kommt bei V. a. bestimmte neurodegenerative Erkrankungen (z. B. eine progressive supranukleäre Blickparese) oder einer vaskulären Pathologie eine besondere Bedeutung zu.

Das Diagnosegespräch

Das Diagnosegespräch folgt der interdisziplinären Diagnosestellung und ist der Ausgangspunkt für die individuell angepasste Beratung, Behandlung und Begleitung der Betroffenen. Generell haben Patienten das Recht, klar und angemessen über ihren Gesundheitszustand informiert zu werden, ausser sie verzichten explizit darauf, aufgeklärt zu werden (28). Aufgrund der Tragweite der Diagnose sollte die Übermittlung mit grosser Sorgfalt erfolgen. Einfache, klare, gegebenenfalls den kognitiven Einschränkungen angepasste Worte erleichtern das Verständnis der Diagnose und deren Bedeutung und ermöglichen in der Folge eine offene Kommunikation innerhalb der Familie oder des Bezugssystems. Den Patienten und ihren Angehörigen muss ausreichend die Möglichkeit angeboten werden, Fragen zu stellen (29). Bei Bedarf sollte ein weiteres ergänzendes Beratungsgespräch angeboten werden. Das Wissen über die Erkrankung, deren Verlauf, über mögliche künftige Probleme (z. B. Verhaltensauffälligkeiten, Pflegebedarf) und den Umgang mit diesen hilft, die emotionale Belastung zu verringern. Über Unterstützungs- und Begleitungsangebote für Patienten und für ihre Angehörigen zu informieren oder solche bereits anzubieten, kann ein wesentlicher Beitrag für einen gelingenden Umgang mit der Diagnose leisten. Neben der Abgabe von Informationsmaterial ist die ergänzende und begleitende Beratung durch die schweizweit tätige Patienten- und Angehörigenorganisation Alzheimer Schweiz empfohlen.

Spezielle Aspekte

Bei Einschränkungen kognitiver Funktionen können Fragen nach der Fahreignung und der Urteilsfähigkeit aufkommen. Im Rahmen der Abklärung in der Memory Clinic erfolgt keine Fahreignungsprüfung im eigentlichen Sinne. Bei auffälligen kognitiven oder verhaltensbezogenen Leistungseinschränkungen kann jedoch wichtig sein, auf deren Relevanz für die Fahreignung zu verweisen und gegebenenfalls weitere Schritte einzuleiten.

Bei Fragen der Urteilsfähigkeit sollten diese bedarfsweise separat untersucht und besprochen werden. Es ist jedoch im Rahmen des Diagnosegesprächs sinnvoll, Betroffene bereits im frühen Krankheitsstadium darauf hinzuweisen, sich bezüglich rechtlicher, finanzieller und medizinischer Angelegenheiten rechtzeitig beraten zu lassen und entsprechende Massnahmen (z. B. Vorsorgeauftrag, Patientenverfügung) nach eigenem Willen in die Wege zu leiten.

Weiterer Verlauf und Nachbetreuung

Im Anschluss an das Diagnosegespräch sollten nebst Empfehlungen zu medikamentösen und nicht medikamentösen Massnahmen (3) auch Informationen zu sozialrechtlichen oder lebenspraktischen Beratungsstellen, Selbsthilfegruppen sowie zu konkreten regionalen Betreuungs- und Entlastungsmöglichkeiten angeboten werden. Zudem ist je nach Prognose und individuellem Bedarf eine Verlaufsuntersuchung bzw. eine Langzeitbetreuung zu planen. Eine Verlaufsuntersuchung in der Memory Clinic dient einer erneuten diagnostischen Standortbestimmung, der Beratung und gegebenenfalls der Anpassung der Behandlung und Begleitung. Diese sollten in enger Abstimmung mit den Betroffenen, ihren Angehörigen und den ärztlichen, therapeutischen, pflegerischen sowie den involvierten Fachstellen erfolgen.

Ausblick

Obwohl die Schweiz über ein relativ dichtes Netzwerk spezialisierter Memory Clinics verfügt (30) und eine genaue und frühe Diagnosestellung zu empfehlen ist (21, 31), wird immer noch bei einem hohen Anteil der an Demenz erkrankten Menschen keine oder keine ausreichend genaue Diagnose gestellt. Auch besteht Forschungsbedarf sowohl für ein besseres Verständnis geschlechtsspezifischer Aspekte als auch zur Validierung und evidenzbasierten Implementierung diagnostischer Methoden und Abläufe, die diese Aspekte berücksichtigen (32). Des Weiteren braucht es verbesserte Methoden zur Beurteilung kognitiver und neuropsychiatrischer Symptome sowie der Alltagsaktivitäten in spezifischen Patientengruppen, wie zum Beispiel bei Patienten mit Erkrankungen in jungem Erwachsenenalter, bei Patienten mit unterschiedlichem kulturellen Hintergrund, insbesondere bei Migranten, und bei weiteren Patientengruppen.

Fortschritte im Bereich der klinischen, neuropsychologischen und Biomarker-Diagnostik sowie digitale Methoden zur Symptomerfassung werden in den nächsten Jahren die klinische Praxis in Bezug auf die Erstellung individueller Risikoprofile voraussichtlich erheblich verbessern und erweitern. Dies wird sowohl die Früherkennung als auch das Monitoring von Demenzerkrankungen erleichtern. Darüber hinaus werden neurokognitive Prozesse, Alltagsbeeinträchtigung und neuropsychiatrische Symptome zunehmend im alltäglichen Lebensumfeld und bei Bedarf engmaschiger erfasst und interpretiert werden können. Diese Entwicklungen bieten die Aussicht auf eine präzisere und zugleich alltagsrelevante Diagnostik, was eine personalisierte Beratung und Begleitung erleichtern und bedarfsgerecht optimierte Interventionen ermöglichen wird. Die in naher Zukunft erwarteten krankheitsmodifizierenden Behandlungen, wie zum Beispiel die Anti-Amyloid-Antikörper, erfordern eine genaue, Biomarker-gestützte Identifizierung der anvisierten Pathologie und eine Bewertung der mit der Behandlung verbundenen Risiken.

Diese Innovationen könnten zwar einen grossen Fortschritt darstellen, ihre Umsetzung ist jedoch auch mit grossen Herausforderungen verbunden (30). Dazu gehören Fragen zu ethischen Aspekten, zur Anpassung in der Versorgung, zur Verfügbarkeit von Ressourcen, zur Akzeptanz und zu Fragen der angemessenen Anwendung neuer Möglichkeiten.

Prof. Dr. med. Julius Popp

Department of Adult Psychiatry and Psychotherapy

University of Zürich

Lenggstrasse 31

CH-8032 Zürich

julius.popp@uzh.ch

Julius Popp 1, 2*, Tatjana Meyer-Heim 1, 3, Markus Bürge 1, 3, Michael M. Ehrensperger 1, 4,

Ansgar Felbecker 1, 5, Hans Pihan 1, 5, 6, Nadège Barro-Belaygues 1, 3, 6, Christian Chicherio 1,

Bogdan Draganski 1, 5, Gaby Bieri 1, 3, Irene Bopp-Kistler 3, 7, Andrea Brioschi 8, Matthias Brühlmeier 9, Karin Brügger 1, 4, Gianclaudio Casutt 4, 10, 11, Valentina Garibotto 9, Petra Gasser 4,

Dan Georgescu 1, 2, Anton Gietl 12, Andrea Grubauer 4, Freimut Jüngling 9, Sonja Kagerer 12,

Eberhard Kirsch 13, Vera Kolly 4, Gabriela Latour Erlinger 1, 4, 12, Andreas Monsch 4, Laura Rinke 1, 4, Rafael Meyer 1, 2, 14

1 Swiss Memory Clinics (SMC)

2 Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Alterspsychiatrie und -psychotherapie (SGAP)

3 Schweizerische Fachgesellschaft für Geriatrie (SFGG)

4 Schweizerische Vereinigung für Neuropsychologie (SVNP)

5 Schweizerische Neurologische Gesellschaft (SNG)

6 Spitalzentrum Biel

7 mediX Gruppenpraxis Zürich

8 Centre hospitalier universitaire vaudois

9 Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Nuklearmedizin (SGNM)

10 Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Verkehrspsychologie

11 Swiss Insurance Medicine (SIM)

12 Psychiatrische Universitätsklinik Zürich

13 Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Neuroradiologie

14 Psychiatrische Dienste Aargau AG

Danksagung

Wir danken Dr. phil. Stefanie Becker, Direktorin Alzheimer Schweiz, für wertvolle Kommentare.

Abkürzungen

AD Alzheimer’s disease (Alzheimer Erkrankung)

ADL Activities of Daily Living

BPSD Behaviorale and Psychologische Symptome der Dementia IADL Instrumental Acitivities of daily living

CT Computertomographie

MCI Mild Cognitive Impairment

MMSE Mini-Mental-Status-Examination

MoCA Montreal-Cognitive-Assessment

MRT Magnetresonanztomographie

PET Positronen Emissions-Tomographie

SMC Swiss Memory Clinics

Historie

Manuskript eingegangen: 19.02.2025

Angenommen nach Revision: 24.02.2025

Version française

Introduction

Représentant les centres suisses de traitement des démences et des troubles cognitifs apparentés, l’ association Swiss Memory Clinics (SMC) s’ engage depuis de longues années pour une qualité optimale de la prise en charge des démences sur l’ ensemble du territoire national. Des groupes de travail formés de membres de SMC et des experts des diverses disciplines et institutions ont préparé les présentes recommandations, en se fondant sur la publication de 2018 (1). Cette mise à jour vise à refléter l’ état actuel des possibilités de diagnostic, à faire connaître les développements en la matière et à exposer succinctement les principaux outils de diagnostic. Le document se limite aux méthodes de diagnostic autorisées et disponibles en Suisse. Des informations détaillées sur les différents chapitres sont à disposition sur le site https://www.swissmemoryclinics.ch/fr/developpement-de-qualite/normes-de-qualite/diagnostic/chapitres-thematiques/. Le groupe d’ experts a principalement pour but d’ améliorer le diagnostic précoce et différentiel des démences et de proposer un guide utile pour la pratique clinique au quotidien. En complément des présentes recommandations relatives au diagnostic, SMC a récemment publié des recommandations concernant le traitement des démences (2).

Dans le présent texte, nous renonçons à utiliser aussi bien la forme masculine que féminine de désignation des personnes. La forme masculine vaut dans tous les cas pour les deux genres, à moins que le contraire ne soit spécifié.

Recommandations générales pour la procédure diagnostique chez le médecin de famille et dans les cliniques de la mémoire

Recommandations pour le médecin de famille

Le dépistage à grande échelle n’ est pas recommandé parmi la population d’ âge avancé (3, 4). En lieu et place, on préférera la détection des cas («case finding»), une stratégie visant les individus qui présentent des facteurs de risque ou des symptômes d’ une possible pathologie démentielle («drapeaux rouges» [red flags]) (3). La détection des drapeaux rouges incombe à la médecine de premier recours (Fig. 1 avec algorithme recommandé). Selon les cas, le bilan diagnostique sera poursuivi par médecin de famille ou dans une Memory Clinic. Si la consultation du patient présentant des symptômes de type «drapeaux rouges» n’ est pas possible chez le médecin de famille, un service mobile de consultation gériatrique ou psychogériatrique pourra se rendre à son domicile. Il en va de même pour les patients présentant des symptômes de ce type dans les EMS.

Le Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE) (5), de préférence complété par le test de l’ horloge, figure souvent parmi les tests cognitifs réalisés dans les cabinets médicaux. Le test de détection de la démence (DemTect) est également répandu en Suisse (6). Mais de façon générale, il est recommandé d’ opter pour le Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (7), en raison de sa sensibilité élevée, de sa mise à disposition gratuite dans différentes langues et de ses résultats concluants dans la pratique.

Déroulement dans la Memory Clinic

Diagnostic interdisciplinaire par des médecins spécialistes (psychiatre de l’ âge avancé, gériatre, neurologue, en tant que membre de l’équipe de la Memory Clinic ou disponible dans le réseau de la Memory Clinic) et des neuropsychologues:

• Anamnèse et hétéro-anamnèse complètes, sur la base d’ entretiens semi-standardisés

• Status psychiatrique et somatique

• Tests neuropsychologiques

• Imagerie (neuroradiologie, évt. médecine nucléaire)

• Examens de laboratoire (prélèvement sanguin, évt. ponction lombaire)

• Pose du diagnostic dans le cadre d’ une conférence interdisciplinaire selon les codes CIM-10 ou DSM-5 (codage selon la liste CIM-10 ou, à l’ avenir CIM-11)

• Classement diagnostique des troubles cognitifs selon leur degré de sévérité. Le degré de sévérité est défini en fonction des limitations de performances et des répercussions invalidantes au quotidien

– Trouble cognitif subjectif (trouble cognitif non objectivable sur les plans clinique et neuropsychologique)

– Trouble cognitif léger (mild cognitive impairment ; trouble neurocognitif léger selon le DSM-5)

– Démence (trouble neurocognitif majeur selon le DSM-5)

– légère: limitation des AIVQ seulement (activités instrumentales de la vie quotidienne) (8), p. ex. tenir son ménage, gérer son argent

– modérée: limitation des ABVQ également (activités de base de la vie quotidienne) (9), p. ex. se nourrir, s’ habiller

– sévère: dépendance totale

• Statuer sur l’ étiologie du trouble cognitif

• Entretien d’ annonce du diagnostic et de conseil avec le patient et ses proches, voir plus bas

• Traitement médicamenteux et non médicamenteux, voir recommandations de SMC relatives au traitement (10)

• Durant l’ évolution de la maladie, la clinique de la mémoire sert d’ interlocutrice pour différentes questions, telles que le suivi clinique, la réévaluation du diagnostic et l’ adaptation des mesures de prise en charge, ainsi que pour la mise en œuvre de conseils et d’ accompagnement, etc.

Anamnèse

Il est essentiel de documenter en détail la phase prodromique et les facteurs de risque, et de décrire le début de la maladie et son évolution avec ses éventuelles fluctuations, en distinguant bien la perception propre au patient et celle de l’ entourage. Une anamnèse familiale doit être effectuée et inclure l’ âge et la cause de décès des parents, des frères et sœurs et, le cas échéant, des enfants. S’ il existe des cas de démence dans la famille, les données concernant l’ âge du début de la maladie et son évolution seront également saisies. En outre, une anamnèse personnelle complète s’ impose, portant notamment sur la médication.

Anamnèse par système

• Substances nocives: alcool, nicotine, drogues, abus de médicaments

• Système cardiovasculaire: troubles cardio-pulmonaires, arythmies cardiaques (fibrillation auriculaire notamment)

• Alimentation: évolution du poids, comportement alimentaire, y compris état dentaire/dysphagie, digestion, troubles du transit (p. ex. constipation), régimes, diabète

• Miction: incontinence urinaire, dysurie, mictions fréquentes et urgentes

• Sensations: vertiges, céphalées, douleurs générales

• Récupération: somnolence diurne, troubles de l’ endormissement et du sommeil, rêves/cauchemars, agitation nocturne, parasomnies, ronflements, phases d’ apnée

• Mobilité: aides à la marche, chutes (fréquence, cause, déroulement), perte d’ assurance dans les déplacements

• Symptômes neurologiques: troubles de la coordination et de l’ équilibre, tremblements, tonicité, faiblesse générale (déficits de la motricité/sensibilité), troubles de la motilité oculaire, dysphagie, crampes

• Langage: élocution difficile ou ralentie, difficultés à trouver ses mots

• Organes sensoriels: baisse de l’ acuité visuelle et auditive, altération du goût et de l’ odorat

• État psychique: symptômes dépressifs incluant les tendances suicidaires, troubles anxieux, irritabilité, apathie, agitation, délire, hallucinations

• Anamnèse de délirium

• Enfin: symptômes n’ ayant pas encore été abordés

Anamnèse psychosociale

Le diagnostic des démences intervient souvent chez des patients âgés polymorbides, dont les capacités de communication et la perception de la maladie sont restreintes, ce qui peut compliquer l’ anamnèse.

Un entretien semi-structuré avec le patient et ses proches servira à l’ anamnèse des problèmes dus aux troubles cognitifs vécus et observés au quotidien. Des questions ciblées porteront sur les performances mnésiques, les capacités de langage et de communication, l’ aisance à planifier et gérer les tâches, ainsi que les capacités d’ orientation dans le temps et l’ espace. La gestion du quotidien, en particulier le degré d’ autonomie dans les activités quotidiennes primaires (de base) ou étendues (instrumentales), sera abordée de manière détaillée. Il s’ agit de connaître le besoin d’ aide, l’ assistance requise ou les interventions déjà mises en place. Des informations seront recueillies sur la conduite d’ un véhicule (sécurité et compétence au volant) et l’ utilisation des transports publics. Il est par ailleurs recommandé de se renseigner sur les activités sociales, les hobbies et les contacts sociaux entretenus.

L’ entretien sera complété par des questions précises portant sur la latéralisation, le langage primaire et élaboré, l’ histoire de vie – comme la formation, la carrière professionnelle, la situation familiale et le mode de vie actuel. Aux anamnèses médicale et psychosociale s’ ajoutent d’ ordinaire des autoévaluations et des hétéroévaluations, réalisées au moyen de différentes échelles, telles que:

• Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE)

• Nurses’ Observation Scale for Geriatric Patients (NOSGER)

• Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI)

• Neuro-psychiatric Inventory (NPI)

• Échelle de dépression gériatrique (GDS)

• Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)

Collecte de données sur les aptitudes au quotidien

Les activités de la vie quotidienne (AVQ) comprennent les activités de base (ABVQ) et les activités instrumentales de la vie quotidienne (AIVQ). Dans les ABVQ figurent les actes comme manger/prendre la nourriture, se laver, s’ habiller, aller aux toilettes, contrôler ses sphincters, se lever de son lit ou d’ une chaise, marcher et se déplacer (avec ou sans aide à la marche). Les AIVQ englobent les compétences telles que préparer des repas, faire le ménage et la lessive, gérer son argent, téléphoner, faire ses achats, prendre ses médicaments et se déplacer en utilisant un moyen de transport.

La collecte des données sur la vie quotidienne d’ un patient, dans le cadre de son anamnèse ou de l’ hétéro-anamnèse, repose en principe sur quatre sources possibles:

1. Observation du patient

2. Questionnaire standard soumis au patient

3. Questionnaire standard soumis aux proches ou aux accompagnants

Collecte de données lors d’ une visite à domicile (chez le patient, à l’ EMS, etc.)

Il faut toujours distinguer entre les aptitudes qui étaient celles du patient par le passé et ses aptitudes actuelles, et relever le décalage entre l’ auto-anamnèse et l’ hétéro-anamnèse. Il peut être intéressant de savoir si la personne utilise les nouvelles technologies (AIVQ), ou si elle préfère ne pas s’ aventurer en terrain inconnu. La saisie standardisée des aptitudes présentes au quotidien dans le cadre d’ une hétéro-anamnèse (11), au besoin séparée de l’ entretien avec le patient, est indispensable à la pose de tout diagnostic de démence.

Pour des raisons pratiques, une investigation à domicile est souvent impossible dans le cadre des examens de la clinique de la mémoire. Cette procédure peut être faite dans une étape séparée, p. ex. par des services se rendant au domicile, ou par des spécialistes (soins, ergothérapie).

Examen somatique

L’ examen somatique est dirigé selon les comorbidités et le diagnostic suspecté (élément principal de la problématique) et doit être adapté en conséquence (Tab. 1).

Status psychopathologique et symptômes comportementaux et psychologiques de la démence (SCPD)

Outre les troubles cognitifs et les limitations dans les activités de la vie quotidienne, les patients atteints de démence présentent souvent, au cours de l’ évolution de la maladie, différents symptômes psychiatriques et comportementaux qui les handicapent de façon importante et compliquent leur traitement et leur prise en charge (12). Il peut s’ agir de troubles psychiques indépendants de la démence, ou reliés à celle-ci. Pour désigner les symptômes neuropsychiatriques se manifestant dans le cadre ou à la suite de la démence, le terme de «symptômes comportementaux et psychologiques de la démence» (SCPD) a été proposé. Pour l’ évaluation et le traitement, il est essentiel de prendre en compte les facteurs aussi bien biologiques et psychologiques qu’ environnementaux. À noter que les symptômes neuropsychiatriques peuvent apparaître avant le stade de la démence, au stade MCI (trouble cognitif léger) et peuvent même précéder les troubles cognitifs (13, 14). Les symptômes neuropsychiatriques se manifestant de façon précoce ont pour corollaire une aggravation plus rapide de la cognition et des fonctionnalités au quotidien (15).

Examen de base

• Évaluation clinique de la présence de symptômes psychiques

– Évaluation subjective par le patient

– Hétéroévaluation par les proches ou par des personnes connaissant bien le patient

– Examen psychopathologique de base

– Recherche d’ une éventuelle comorbidité psychiatrique, en particulier trouble dépressif, ou d’ un état confusionnel aigu

• Pondération des informations dans le processus de diagnostic

• Prise en compte des comorbidités psychiatriques primaires et des symptômes neuropsychiatriques/SCPD dans les propositions thérapeutiques relatives aux troubles cognitifs

• Transmission du cas vers une consultation spécialisée, en particulier lorsque les symptômes psychiatriques sont modérés à sévères, s’ il y a suspicion ou confirmation de comorbidités psychiatriques, s’ il y a des implications complexes pour la famille ou si la question d’ éventuelles mesures restreignant la liberté de mouvement se pose.

Optionnel

• L’ utilisation d’ une grille de description psychopathologique est recommandée (AMDP).

• L’ utilisation d’ échelles psychopathologiques spécifiques, p. ex. NPI-Q, est également recommandée. En cas de suspicion de dépression, l’ échelle de dépression gériatrique (GDS) (16) ou le Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) (17) sont également recommandés, si le patient se trouve encore au stade précoce de la démence.

• Traitement des comorbidités psychiques à la clinique de la mémoire: selon compétences et disponibilité

Examen neuropsychologique

Le principal bénéfice des tests cognitifs dans le cadre d’un examen neuropsychologique est le dépistage précoce et la quantification des dimensions cognitives altérées. Un profil des forces et faiblesses cognitives constitue en outre une base importante pour une psychoéducation, un conseil et un traitement adaptés aux besoins des patients et de leurs proches. À l’ instar de la présentation différenciée des troubles neurocognitifs du DSM-5 (18), l’ examen neuropsychologique complet vise à fournir des indications tant qualitatives que quantitatives sur les six dimensions suivantes:

• Attention: attention soutenue, attention divisée, attention sélective, vitesse de traitement

• Fonctions exécutives: planification, prise de décision, mémoire de travail, analyse des feedbacks/correction des erreurs, comportement différant des habitudes/inhibition comportementale, flexibilité mentale

• Apprentissage et mémoire: mémoire immédiate, mémoire à court terme (y c. rappel libre ou indicé et reconnaissance), mémoire à long terme (sémantique, autobiographique), apprentissage implicite

• Langage: production langagière (y c. dénomination et recherche de mots, fluence verbale, grammaire et syntaxe), compréhension

• Capacités perceptivo-motrices: capacité visuo-spatiales, visuo-constructives, perceptivo-motrices, praxies, gnosies

• Cognition sociale: reconnaissance des émotions, capacité d’ empathie (théorie de l’ esprit), changements de comportement

L’ évaluation des performances reposera sur:

• la capacité mesurée lors des tests (au moins deux méthodes de tests par domaine, p. ex. mémoire verbale et visuelle), ainsi que

• l’ observation/les données anamnestiques.

À l’ exception de la dimension «cognition sociale» (pour laquelle des instruments sont en cours de développement), il existe pour tous les aspects cognitifs des instruments de test qui ne nécessitent pas un investissement excessif en temps. Il s’ agit d’ utiliser des instruments qui définissent des normes prenant en compte l’ âge, le genre et la formation des personnes examinées.

Un tel examen standard sera complété par des instruments neuropsychologiques supplémentaires appropriés si le niveau cognitif initial est élevé, si des questions se posent à propos de l’ aptitude au travail, ainsi que pour les formes de démence rares ayant des modèles de référence cognitifs spécifiques.

Procédure pratique

Le standard minimum requis consiste à réaliser un bref test cognitif dont les résultats permettront de choisir la bonne option pour l’ examen neuropsychologique approfondi, compte tenu des informations tirées de l’ anamnèse, de l’ hétéro-anamnèse et en particulier des AVQ de base et des AIVQ. Le MoCA (7) ou le MMSE (5) combiné au test de l’ horloge (19) sont recommandés et font ainsi partie intégrante de la méthode standardisée. Un test cognitif différencié peut s’ avérer superflu pour les patients atteints de démence avancée.

Dans le cadre de l’ examen neuropsychologique, on appliquera dans un premier temps la méthode rapide, car elle permet de choisir la méthode et le niveau adéquats pour l’ examen neuropsychologique complet, en tenant compte des informations issues de l’ anamnèse et de l’ hétéro-anamnèse. Par la suite, une évaluation cognitive personnalisée et complète sera réalisée sur la base d’ hypothèses. Le résultat du test rapide, associé aux informations concernant l’ âge, le niveau de formation, les compétences linguistiques et le statut professionnel, permet de choisir une batterie appropriée de tests cognitifs complets, à l’ aide d’ un algorithme (Suppl. Fig.) (20). Pour les patients dont les capacités cognitives ne sont pas (encore) gravement altérées, l’ examen neuropsychologique approfondi constitue la norme dans les Memory clinic. En Suisse alémanique, le «Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’ s Disease – Neuropsychological Assessment Battery (CERAD-NAB)», enrichi de tests mesurant la vitesse de traitement et les fonctions exécutives (CERAD-Plus), est une batterie de tests dûment standardisés et validés qui connaît un grand succès. Cette batterie est en revanche substituée en Suisse romande par une combinaison de tests cognitifs équivalents, dont la sélection est guidée par des hypothèses et constitue la base d’ un examen neuropsychologique personnalisé. Les éléments du test CERAD-Plus, y compris la possibilité de les évaluer, les tests utilisés en Suisse romande, ainsi qu’ une liste plus exhaustive de tests sont gratuitement à disposition sur le site www.swissmemoryclinics.ch/fr/.

Examen de groupes de patients particuliers

L’ examen est particulièrement complexe dans les cas suivants: (a) contexte d’ immigration avec compétences linguistiques limitées dans la langue de l’ examen (le cas échéant, il est judicieux de faire appel à un interprète interculturel, ce qui permet à long terme d’ épargner des ressources), (b) déficits sensoriels pour lesquels il n’ existe généralement pas de normes de référence, (c) troubles du développement intellectuel, (d) haut potentiel, (e) personnes très âgées (> 90 ans). Dans de telles conditions, l’ examen cognitif et son interprétation doivent s’ adapter à la situation individuelle et requièrent une vaste expertise neuropsychologique. En outre, il faut dans tous les cas tenir compte des troubles somatiques et psychiatriques ou des médicaments entravant les capacités cognitives, qui peuvent créer un biais dans l’ évaluation.

Évaluation et interprétation

La classification recommandée est celle que propose l’ Association suisse des neuropsychologues (ASNP) https://neuro.psychologie.ch/fr dans ses lignes directrices pour la classification et l’ interprétation des résultats aux tests neuropsychologiques, qui définit sept catégories. Le rapport sur l’ examen neuropsychologique devra indiquer en toute transparence le type de données sur lesquelles reposent les conclusions. En outre, il convient de prendre brièvement position sur le tableau clinique. Il est très utile de représenter dans un graphique les résultats des tests cognitifs sur la base des six dimensions cognitives selon le DSM-5. Il est encore judicieux et souhaitable – sur la base des résultats des tests cognitifs et de réflexions d’ ordre fonctionnel et neuro-anatomique – d’ envisager les hypothèses relatives à l’ étiologie d’ un trouble existant. Les réflexions sur l’ étiologie concrète et le diagnostic différentiel n’ ont évidemment de sens qu’ à condition d’ y intégrer toutes les données recensées à la clinique de la mémoire.

Diagnostic de laboratoire

Diagnostic sanguin

Examen de base

• Formule sanguine, protéine C-réactive

• Glucose

• Sodium, potassium, calcium corrigé

• Créatinine, eGFR

• TGO (transaminase glutamique oxalacétique), TGP (transaminase glutamique pyruvique), γ-GT (gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase)

• TSH (thyréostimuline)

• Vitamine B12, acide folique

• Cholestérol, cholestérol HDL, triglycérides (statut lipidique chez les moins de 80 ans)

Examens complémentaires en cas de suspicion spécifique ou de résultats pathologiques des examens de base

• Vitamine D

• Sérologies syphilis et borréliose, test VIH

• CDT (carbohydrate deficient transferrin)

• T3L, T4L, hormone parathyroïdienne, cortisol

• Numération sanguine différentielle, VS, INR

• CK (créatine kinase), urée, acide urique, bilirubine, phosphate, chlorure, magnésium, zinc

• Profil glycémique journalier, HbA1c

• Vitamine B1, vitamine B6, niacine, homocystéine, holotranscobolamine et/ou acide méthylmalonique

• Ferritine, transferrine

• Cuivre, céruloplasmine, status urinaire avec clairance du cuivre dans les urines de 24h

• Dépistage de substances toxiques (plomb, mercure)

• Dépistage de drogues (p. ex. benzodiazépines)

• Monitorage de drogues

• Anticorps des encéphalites auto-immunes ou paranéoplasiques

• Paramètres de vascularites

• Génotypage de l’ ApoE (p. ex. dans le cadre de la recherche, en cas de traitement anti-amyloïde prévu avec anticorps monoclonaux)

Diagnostic du liquide céphalo- rachidien (LCR)

Diagnostic standard pour les indications suivantes (21):

Exclusion des formes autres que les démences primaires dégénératives, en particulier ici les maladies inflammatoires chroniques du SNC.

• En présence de démences à progression rapide, atypiques ou précoces (première manifestation avant l’ âge de 65 ans).

• Ponction diagnostique ou de décharge en cas de suspicion d’ hydrocéphalie à pression normale.

• Diagnostic de soutien pour confirmer une neurodégénérescence, une pathologie tau et/ou une pathologie amyloïde ; s’ il y a une indication clinique spécifique et une investigation en cas de suspicion de la maladie d’ Alzheimer à un stade précoce (y compris le stade du trouble cognitif léger, MCI).

En cas de suspicion d’ une affection inflammatoire chronique du SNC, il convient, en plus du diagnostic de base du LCR, de déterminer des bandes oligoclonales et éventuellement des sérologies syphilis et borréliose, ainsi que d’ autres déterminations sérologiques. La recherche de l’ amyloïde bêta (Aβ42 ; Aβ42/Aβ40), de la protéine phospho-tau et de la protéine tau, en tant que biomarqueurs pour les démences, est appropriée comme diagnostic précoce et diagnostic différentiel dans l’ investigation des troubles cognitifs. Elle est généralement utilisée comme une partie du diagnostic de base dans le LCR. S’ il y a, cliniquement, une suspicion de la maladie de Creutzfeldt-Jakob, il est possible de déterminer en plus la protéine 14-3-3 et de faire une RT-QuIC (Real-Time Quaking-Induced Conversion) dans le LCR. Il est recommandé de procéder à une information individualisée des patients relative à l’ examen prévu des biomarqueurs et aux résultats possibles (21).

Imagerie diagnostique

Neuroradiologie

Les examens d’imagerie cérébrale réalisés dans le cadre du diagnostic des démences remplissent deux fonctions essentielles:

1. exclure les causes secondaires d’ une démence, comme la présence d’ une masse, les troubles de circulation du LCR, ainsi que les modifications d’ origine vasculaire, métabolique ou inflammatoire ;

2. contribuer à la différenciation étiologique et à la classification des formes primaires de démence.

L’ imagerie cérébrale peut contribuer au diagnostic et au diagnostic différentiel entre la maladie d’ Alzheimer et d’ autres démences, p. ex. fronto-temporales, bien qu’ à l’ heure actuelle, l’ imagerie structurelle ne suffit pas à elle seule à trancher entre ces étiologies (22). Cette imagerie est d’ une grande utilité pour identifier et évaluer les lésions intracérébrales ainsi que pour en estimer le nombre et la localisation. Ainsi, l’ imagerie doit être reconnue pour son apport à l’ évaluation globale et à la classification différentielle des tableaux cliniques des démences, en combinaison avec l’ anamnèse et les résultats cliniques, neuropsychologiques et d’ autres ordres.

Examen de base

L’ imagerie structurelle avec tomographie par résonance magnétique crânienne (IRM cérébrale) – ou à défaut, en cas de contre-indication à l’ IRM, par tomodensitométrie crânienne (CT) – fait partie du diagnostic de base.

Imagerie par résonance magnétique cérébrale

(IRM cérébrale)

Le choix se portera en général sur l’ IRM, notamment en raison de l’ absence d’ exposition au rayonnement et parce que la résolution des images anatomiques est bien meilleure qu’ avec un CT. Si cela est possible, on privilégiera une IRM 3 Tesla plutôt que 1,5 Tesla. Les recommandations détaillées sur le protocole d’ examen figurent sur le site de la SMC (https://www.swissmemoryclinics.ch/fr).

Tomodensitométrie cérébrale (scanner cérébral, CT)

À défaut d’IRM et en cas de contre-indication (p. ex. stimulateur cardiaque, implants numériques, claustrophobie majeure), on procédera à un scanner cérébral (CT). Le CT sans produit de contraste est en règle générale suffisant pour confirmer ou exclure la présence d’ une masse, d’ un hématome sous-dural ou d’ une hydrocéphalie et, avec certaines réserves, pour identifier une démence vasculaire.

Sonographie des vaisseaux irriguant le cerveau

En cas de démence vasculaire ou de formes mixtes de démence vasculaire et dégénérative, il peut être pertinent d’ évaluer les sténoses des vaisseaux cérébraux par échographie Doppler ou duplex.

Médecine nucléaire

Tomographie par émission de positons (TEP) au fluorodésoxyglucose (18F) (TEP–FDG)

La TEP-FDG permet de représenter en images le métabolisme régional du glucose et de le comparer avec des valeurs normales. Il s’ agit de la technique d’ imagerie de médecine nucléaire la mieux validée pour le diagnostic des démences. Les recommandations relatives à la TEP-FDG figurent dans le Tab. 2.

La TEP-FDG présente une sensibilité élevée pour la mise en évidence de modifications fonctionnelles et neurodégénératives du traitement cortical des informations. Elle convient parfaitement au diagnostic précoce, même au stade de troubles cognitifs légers (MCI). La corrélation topique des aires présentant un dysfonctionnement permet par ailleurs, dans de nombreux cas, de faire la distinction entre la neurodégénérescence précoce fonctionnelle d’ états similaires à la démence (p. ex. en cas de maladie psychiatrique) et des troubles cognitifs d’ origine différente (p. ex. encéphalite limbique).

La TEP-FDG permet aussi de différencier des modèles métaboliques typiques de plusieurs autres démences neurodégénératives moins fréquentes, comme la démence à corps de Lewy et diverses formes de dégénérescences lobaires fronto-temporales– dont notamment les variantes de l’ aphasie primaire progressive (forme sémantique, non fluente et logopénique) et l’ atrophie corticale postérieure (23).

Pour résumer, la TEP-FDG est recommandée comme l’ imagerie moléculaire de premier choix pour le diagnostic des démences neurodégénératives (24). Pour une prise en charge des coûts selon l’ ordonnance sur les prestations de l’ assurance des soins (OPAS), des limitations sont à respecter.

TEP amyloïde

La TEP amyloïde permet de mettre en évidence avec certitude la présence ou l’ absence d’ une pathologie bêta-amyloïde dans le cerveau. Différents traceurs qui se lient aux plaques amyloïdes peuvent être utilisés. Depuis le 1er avril 2020, une obligation de prise en charge par les caisses maladie a été adoptée pour la TEP amyloïde comme examen complémentaire (limitations à respecter) notamment dans les cas peu clairs, après diagnostic du LCR non concluant ou lorsqu’ une ponction lombaire n’ est pas possible ou est contre-indiquée (24).

La mise à disposition prochaine de nouveaux médicaments actifs contre les pathologies amyloïdes élargira le champ d’ intervention clinique.

Imagerie du système dopaminergique: SPECT du transporteur de la dopamine avec l’ ioflupane (123I) et TEP à la 18F-DOPA

Le SPECT des transporteurs de la dopamine à l’ ioflupane (123I) (DaTSCAN®) et la TEP à la 18F-DOPA sont des examens de médecine nucléaire destinés à déterminer la disponibilité cérébrale de la dopamine (25). La mise en évidence d’ un déficit dopaminergique dans le striatum par ces examens permet de distinguer une maladie à corps de Lewy (avec résultat pathologique dans le striatum) et les démences sans corps de Lewy (en particulier Alzheimer) avec résultat normal dans le striatum (26). Swissmedic a autorisé deux produits radiopharmaceutiques pour le SPECT (DaTSCAN® et Striascan®) ainsi que la TEP à la 18F-DOPA pour cette indication.

Analyse génétique

Les personnes atteintes d’ une démence et leurs proches s’ inquiètent souvent de savoir si la maladie est héréditaire. Or il n’ est pas toujours nécessaire, au plan médical, de procéder à des analyses génétiques pour répondre à cette préoccupation (27).

Examen de base

Les professionnels d’ une clinique de la mémoire devront pouvoir:

• identifier les cas de démence familiale,

• peser l’ information dans le cadre de l’établissement du diagnostic,

• poser l’ indication d’ une consultation génétique spécialisée,

• collaborer avec les spécialistes en génétique humaine et documenter cette collaboration,

• discuter avec le patient/les proches de l’ éventuelle annonce vers une consultation en médecine génétique humaine,

• adresser le patient/la famille vers un institut de médecine génétique humaine (habituellement relié à une clinique universitaire). Cette procédure aura notamment lieu dans les cas suivants:

– un apparenté de 1er degré potentiellement atteint et âgé de moins de 50 ans

– deux apparentés de 1er degré potentiellement atteints et âgés de moins de 60 ans

• renseigner et conseiller à propos de la génétique en tant que facteur de risque des pathologies démentielles les plus fréquentes.

Autres examens

S’ appuyant sur des éléments anamnestiques ou des résultats de l’ examen clinique, les examens complémentaires suivants peuvent être appropriés et utiles.

Électroencéphalogramme (EEG)

Une EEG peut fournir des informations utiles dans les cas suivants:

• fluctuations importantes dans la vigilance et l’ orientation, en vue d’ exclure une origine épileptique,

• suspicion de maladie inflammatoire/infectieuse, inflammatoire/auto-immune ou métabolique du SNC (p. ex. encéphalite limbique, encéphalopathie de Hashimoto) et suspicion de la maladie de Creutzfeldt-Jakob.

Diagnostic d’ un trouble du sommeil

Les démences sont souvent accompagnées d’ un besoin accru de sommeil, autrement dit d’ un sommeil nocturne prolongé et d’ une somnolence diurne excessive. Tout comme les maladies organiques du cerveau, les troubles respiratoires associés au sommeil peuvent perturber l’ architecture du sommeil et induire une somnolence diurne excessive, ainsi qu’ une baisse de l’ attention. Ils représentent un facteur de risque indépendant pour des événements cardio-vasculaires et cérébro-vasculaires et répondent souvent aux traitements.

Une somnolence diurne excessive peut être évaluée simplement, au moyen du questionnaire de somnolence d’ Epworth (28). Un examen au cours du sommeil au moyen d’ un appareil (actimétrie, pulsoxymétrie nocturne, polygraphie, polysomnographie) peut être indiqué en cas de:

• somnolence diurne excessive et signes de troubles respiratoires nocturnes, en vue d’ exclure un syndrome d’ apnée du sommeil.

• suspicion d’ un trouble du sommeil paradoxal;

• suspicion de crises d’ épilepsie liées au sommeil.

Test de l’ odorat

Un test de l’ odorat peut fournir un résultat corroborant le diagnostic préliminaire lors du dépistage précoce de la maladie d’ Alzheimer Dans la maladie d’ Alzheimer ainsi que dans la maladie de Parkinson une baisse de l’ odorat peut apparaitre très tôt, accompagnant ou précédent les premiers troubles cognitifs. Différents tests validés sont à disposition.

Analyse de la marche

Outre la cognition, les pathologies neurodégénératives peuvent altérer les fonctions motrices. Les personnes affectées par une démence présentent un risque de chute accru par rapport aux sujets du même âge en bonne santé. Une analyse clinique structurée permet de déterminer l’ assurance à la marche et les risques de chute. Elle aide à poser l’ indication de mesures thérapeutiques ou préventives adéquates (entraînement, moyen auxiliaire de marche, etc.). L’ analyse quantitative de la marche repose sur des tests cliniques validés de la mobilité (p. ex. test «timed up and go»), mais aussi sur des procédés informatisés (les données de mobilité sont saisies numériquement, p. ex. au moyen de capteurs de pression sur un tapis de marche).

Oculomotricité/champ visuel

Un examen clinique de l’ oculomotricité et du champ visuel s’ impose en cas de suspicion de certaines maladies neurodégénératives (p. ex. paralysie supranucléaire progressive) ou de pathologie vasculaire.

Entretien d’annonce du diagnostic

L’ entretien d’annonce du diagnostic fait suite à la pose interdisciplinaire du diagnostic et constitue le point de départ d’ un conseil, d’ un traitement et d’ un accompagnement individualisés. De façon générale, le patient a le droit d’ être informé de manière claire et appropriée sur son état de santé, à moins qu’ il ne renonce explicitement à cette information (29). Étant donné la gravité du diagnostic, celui-ci doit être révélé avec le plus grand soin. L’ emploi de mots simples et clairs, le cas échéant adaptés aux limitations cognitives du patient, facilite la compréhension du diagnostic et sa portée et permet par la suite une communication ouverte au sein de la famille ou du cercle de référence. Il convient de donner au patient et à ses proches suffisamment de possibilités de poser des questions (30). En cas de besoin, un nouvel entretien sera proposé pour compléter le premier. Donner des informations sur les offres de soutien et d’ accompagnement pour les patients et les proches, ou les proposer déjà, peut représenter un soulagement important et contribuer à une meilleure maîtrise de la situation. Il est recommandé de fournir du matériel d’ information aux patients et aux proches, mais aussi de faire connaître les conseils et l’ accompagnement proposés par l’ organisation Alzheimer Suisse sur tout le territoire national.

Aspects particuliers

Lorsqu’ il y a une limitation des fonctions cognitives, les questions d’ une aptitude à la conduite ou d’ une capacité de discernement peuvent se poser(31). Dans le cadre de ses examens, la clinique de la mémoire ne propose pas à proprement parler d’ examen d’ aptitude à la conduite. En cas de limitation des performances cognitives ou comportementales, il peut cependant s’ avérer important de se préoccuper de leur pertinence par rapport à l’ aptitude à la conduite et, le cas échéant, d’ engager les démarches qui s’ imposent.

Si la capacité de discernement (32) doit être déterminée, cela se fera lors d’ une évaluation à part. Dans le cadre de l’ entretien d’ annonce du diagnostic, il est toutefois recommandé d’ évoquer la problématique avec les personnes concernées au stade précoce de la maladie déjà, et de leur suggérer de se faire conseiller sur les plans juridique, financier et médical afin de pouvoir prendre au besoin, de leur propre chef, les mesures nécessaires (p. ex. mandat pour cause d’ inaptitude, directives anticipées).

Suite des démarches et suivi

En lien avec l’ entretien d’annonce du diagnostic, et à côté des recommandations liées aux mesures médicamenteuses et non médicamenteuses (10), il est conseillé de donner des informations sur les services sociaux ou les services de conseil relatifs à la vie de tous les jours, sur les groupes d’ entraide ainsi que sur les possibilités concrètes d’ accompagnement et de décharge disponibles dans la région. Le site www.alzguide.ch tient un registre national de telles offres. Par ailleurs, selon le pronostic et les besoins individuels, il peut être bon de planifier un suivi de l’ évolution ou un accompagnement de longue durée. Un tel suivi à la clinique de la mémoire permet de refaire le point sur le diagnostic, de conseiller et le cas échéant, d’ adapter le traitement et l’ accompagnement. Ces démarches devraient être engagées d’ entente avec les personnes concernées, leurs proches et les services médicaux, thérapeutiques et soignants, ainsi qu’ avec les entités spécialisées.

Perspective

Bien que la Suisse possède un réseau relativement dense de cliniques de la mémoire spécialisées (33) et que la pose précise et précoce du diagnostic soit recommandée (21, 34), la proportion de personnes atteintes de démence et ne bénéficiant pas d’ un diagnostic ou d’ un diagnostic suffisamment précis reste élevée. De plus, davantage d’ efforts sont nécessaires dans la recherche sur les aspects spécifiques aux hommes et aux femmes ainsi que pour l’ implémentation de méthodes et de processus diagnostiques qui tiennent compte de ces aspects (35). De même, il s’ agirait d’ améliorer les méthodes d’ évaluation des symptômes et déficits fonctionnels parmi des groupes spécifiques de patients, comme les patients affectés à un âge jeune ou moyen, les patients issus de différents horizons culturels, en particulier les migrants, ou d’autres groupes de patients.

Les progrès réalisés dans le diagnostic clinique, neuropsychologique et celui des biomarqueurs, ainsi que les méthodes numériques de saisie des symptômes devraient améliorer et élargir de façon considérable, dans les années à venir, la pratique clinique en lien avec l’ établissement de profils de risques individuels. Ces améliorations faciliteront tant le dépistage précoce que le monitorage des troubles cognitifs et démences. En outre, les processus neurocognitifs, les activités de la vie quotidienne et les symptômes neuropsychiatriques pourront être saisis et interprétés de façon plus précise dans l’ environnement quotidien. Ces développements offrent la perspective d’ un diagnostic plus précis et en même temps davantage lié au quotidien, ce qui facilitera un conseil et un accompagnement individualisés et permettra des interventions répondant mieux aux réels besoins. Les nouveaux traitements visant les pathologies cérébrales qui seront probablement bientôt disponibles, comme les anticorps anti-amyloïdes, requerront une identification précise, basée sur les biomarqueurs, de la pathologie visée ainsi qu’ une appréciation précise des risques liés au traitement.