- Oncological care of adolescents and young adults in Switzerland – Experience from St. Gallen

Adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer are internationally defined as individuals aged 15–39 years. Their age, as well as the distinct biological features of their cancers and specific psychosocial needs often place these patients between pediatric and adult oncology. This study retrospectively assessed AYA cancer cases aged 15–25 years at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Switzerland and the Cantonal Hospital St. Gallen from 2021 to 2023, by recording epidemiology, treatment modalities, fertility counseling, psychological support, and clinical trial participation. A total of 75 patients (17 pediatric, 58 adult) were identified, with lymphoma being the most frequent diagnosis. The diagnoses and the treatment approaches differed between both cohorts, with 45 % of the adult patients receiving surgery as the only treatment modality compared to 12 % of the pediatric patients. While fertility counseling was offered to most patients at risk (69 % pediatric, 62 % adult), psychological support for patients who received multimodal treatment was used more frequently in the pediatric setting (93 % vs. 23 %). Clinical trial participation in those who received multimodal treatment was higher among pediatric patients (21 % vs. 3 %). These findings highlight similarities and differences in the care of AYA cancer patients, the reasons for which remain to be further elucidated. Given the lack of a dedicated AYA unit in Switzerland, this analysis provides a basis for planning a structured AYA care model in St. Gallen. A specialized unit could enhance collaboration between pediatric and adult oncologists and other healthcare professionals, ensure access to fertility and psychosocial services, and optimize treatment strategies, to ultimately provide the best care for AYA cancer patients.

Adoleszente und junge Erwachsene (AYA) mit Krebs sind definiert als Personen im Alter von 15–39 Jahren. Ihre Erkrankungen weisen spezifische biologische Eigenschaften auf, und die Betroffenen haben besondere psychosoziale Bedürfnisse, die oft zwischen rein pädiatrischen und erwachsenenonkologischen Versorgungsmodellen liegen. Diese retrospektive Studie analysierte AYA-Patientinnen und -Patienten mit Krebserkrankungen am Ostschweizer Kinderspital und am Kantonsspital St. Gallen, die zwischen 2021 und 2023 diagnostiziert wurden. Erfasst wurden epidemiologische Daten, Behandlungsmodalitäten, Fertilitätsberatung, psychosoziale Unterstützung sowie der Einbezug in klinische Studien. Es wurden 75 Patientinnen und Patienten identifiziert (17 pädiatrisch, 58 erwachsen), wobei Lymphome die häufigste Diagnose darstellten. Die Diagnosen und die entsprechenden Therapien unterschieden sich deutlich zwischen beiden Kohorten: 45% der erwachsenen Patienten erhielten ausschliesslich eine chirurgische Therapie, verglichen mit 12% in der pädiatrischen Kohorte. Während die Fertilitätsberatung den meisten Patienten mit einem entsprechenden Risiko angeboten wurde (69% pädiatrisch vs. 62% erwachsen), war die psychosoziale Unterstützung nach multimodaler Therapie im pädiatrischen Umfeld deutlich häufiger (93% vs. 23%). Auch die Teilnahme an klinischen Studien bei multimodaler Therapie war im pädiatrischen Umfeld höher (21% vs. 3%). Diese Ergebnisse zeigen sowohl Gemeinsamkeiten als auch Unterschiede in der Versorgung von AYA-Patienten mit Krebs auf. Angesichts des Fehlens einer spezialisierten AYA-Station in der Schweiz bietet diese Analyse eine Grundlage für die Planung eines strukturierten AYA-Versorgungsmodells in St. Gallen. Eine spezialisierte Einheit könnte die Zusammenarbeit zwischen Fachkräften der Kinder- und Erwachsenenonkologie stärken, den Zugang zu Fertilitäts- und psychosozialen Diensten konsequent gewährleisten und die Behandlungsstrategien optimieren, um die Versorgung von AYA-Patienten langfristig zu verbessern.

Keywords: AYA, cancer, transition, care, Switzerland

Introduction

Adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer represent a distinct patient population with unique biological and psychosocial needs and challenges. They are defined by the National Cancer Institute as individuals aged 15 to 39 years (1). The spectrum of malignancies is very heterogeneous, including pediatric-type cancers such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) or rhabdomyosarcoma, as well as adult-type cancers like breast or colorectal cancer (2–5). Tumor biology in AYAs often differs from that in pediatric or older adult patients with the same diagnosis, influencing prognosis and treatment response. For instance, AYAs with ALL exhibit fewer favorable cytogenetic abnormalities (e.g., ETV6-RUNX1) and more often markers with poorer prognosis such as BCR-ABL1 and iAMP21 (6). Similarly, breast cancer in younger women is more frequently characterized by aggressive features, including larger tumor size, poor differentiation, and endocrine receptor negativity (7).

Epidemiologically, cancer incidence in AYAs is higher than in children, with approximately 70 000 new cases annually in the U.S. in 2015, compared to 11 000 in the pediatric population (8). Despite this burden, AYA cancer patients remain underrepresented in clinical trials, as many studies focus exclusively on pediatric or adult populations (9–11). Limited enrollment in trials, combined with the diverse tumor landscape and frequent treatment outside specialized oncology centers, has contributed to slower improvement in survival in AYAs compared to other age groups (8, 11–13).

Beyond medical considerations, AYAs face significant psychosocial challenges, including disruption in education, career development, relationships, and family planning which can lead to a decline in quality of life (3, 14). They are more vulnerable to psychological distress, with higher rates of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and fatigue compared to childhood cancer survivors (15). However, there is still limited recognition among healthcare providers about the unique psychosocial challenges and needs for this age group (2).

Specialized AYA units have emerged as a critical solution to bridge these gaps, integrating age-appropriate medical care with psychosocial support (16, 17). Existing pediatric and adult oncology care models, such as family-centered pediatric approaches, are often ill-suited for AYA patients, leaving them in a “No Man’s Land” of care (18, 19). Dedicated AYA units aim to provide comprehensive and tailored support, improving treatment outcomes and quality of life. The development of such units aims to optimize care delivery and address the unique challenges faced by this population.

In Switzerland, there is currently no dedicated AYA unit to provide structured and tailored care for this patient group. With the construction of the new Children’s Hospital of Eastern Switzerland in St. Gallen, located on the campus of the adult hospital, a new AYA concept is currently being elaborated and evaluated. Today, there is already a collaboration between the medical and pediatric oncologists in St. Gallen, as demonstrated by the routine weekly participation of pediatric oncologists in adult CNS, sarcoma, and malignant hematology tumor boards and discussions of patients in the AYA age range. Some young adult patients might already be treated in the Children’s Hospital if they are diagnosed with a pediatric tumor that is rarely seen in adult oncology or if there is a clinical trial for this tumor entity and age. This collaboration is fundamental in the buildup of an AYA unit, as both disciplines are essential to implement the highest quality of medical care. With this article we aim to analyze the current situation in St. Gallen and gain an overview of the epidemiological data of the 2021–2023 cohort of AYA patients of the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Switzerland and the Cantonal Hospital St. Gallen. The gained overview might be informative for other Swiss hospitals.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective data analysis from January 2021 to December 2023, including all AYA cancer patients, which were presented during this period at a tumor board at either the adult or pediatric hospital and who were diagnosed with a malignant disease. Young patients diagnosed with gynecological tumors at the adult hospital are excluded as they are presented at separate tumor boards of the gynecological clinic. Follow-up data was gathered until June 2024. The definition of the AYA age range was set at 15–25 years due to common tumor biology and psychosocial needs in this age group.

Epidemiological data such as age at diagnosis, gender, and tumor entity were recorded, as well as treatment modalities (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy). We further determined how many patients at risk for infertility received fertility counseling, how many patients treated with multimodal approaches were offered psycho-oncological support from diagnosis onwards, and how many patients were included in clinical trials. Patients at risk for infertility were defined as those undergoing multimodal chemotherapy, craniospinal irradiation, gonadal irradiation, and those with surgery to the reproductive organ system. Psycho-oncological support was defined as contact, consultations or support through psycho-oncologists documented in the hospitals’ electronic data system. Counseling by nurses or other disciplines other than psycho-oncologists was not included. We assessed psycho-oncological support and trial inclusion only for patients who received multimodal or multiagent treatment. The parameters chosen for this study are often recommended to assess the efficacy of AYA units (20).

Results

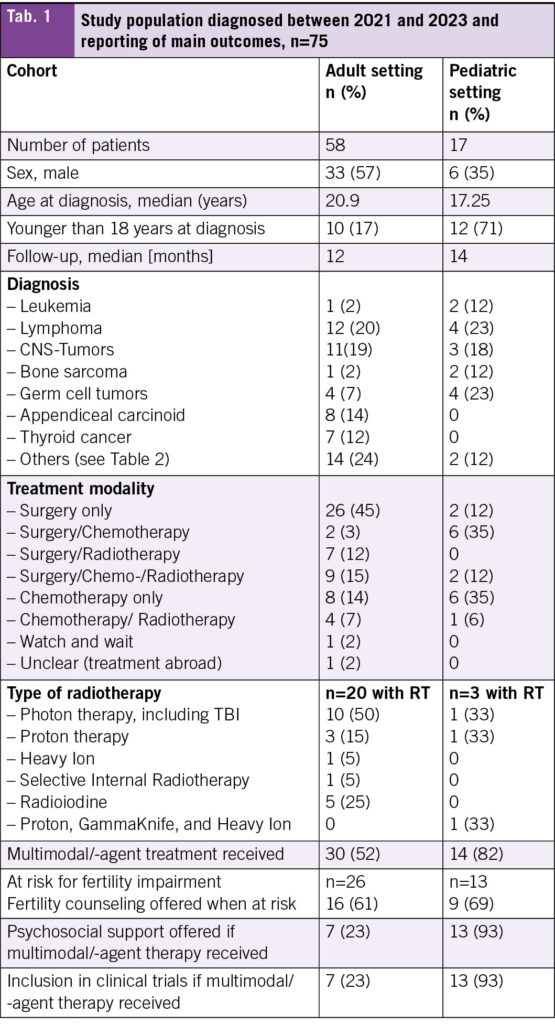

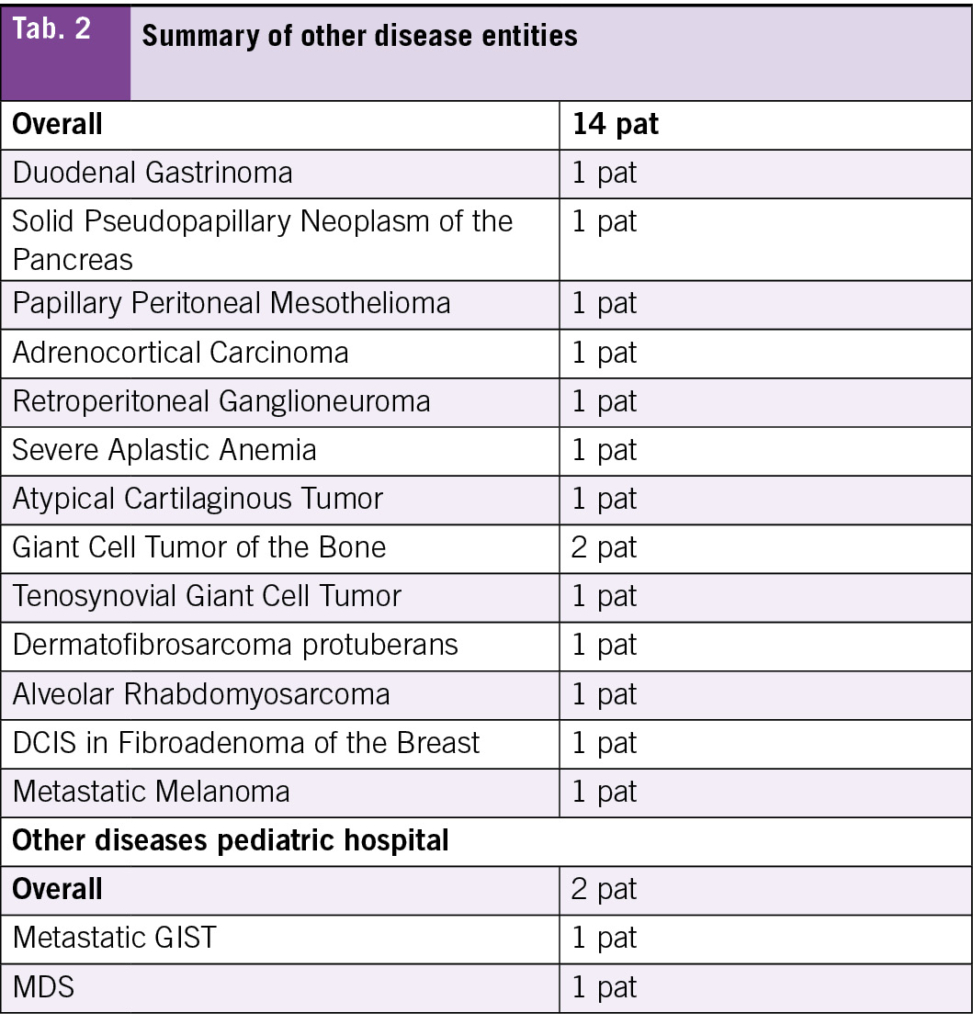

During the specified period, 17 AYA patients were treated in the pediatric hospital and 58 at the adult hospital. The median age at diagnosis was 17 years in the pediatric cohort and 21 years in the adult cohort, with follow-up time of 12 months and 14 months respectively (Tab. 1). A total of 71 % of the patients treated in the pediatric hospital were younger than 18 years at diagnosis compared to 17 % of those treated in the adult hospital. The most frequent diagnosis in those treated in the adult hospital was lymphoma (21 %), followed by tumors of the CNS (19 %) (Tab. 1, Tab. 2). The most frequent diagnoses in those treated in the pediatric hospital were lymphoma with germ cell tumors being equally frequent (23 %), followed by tumors of the CNS (18 %) (Tab. 1, Tab. 2).

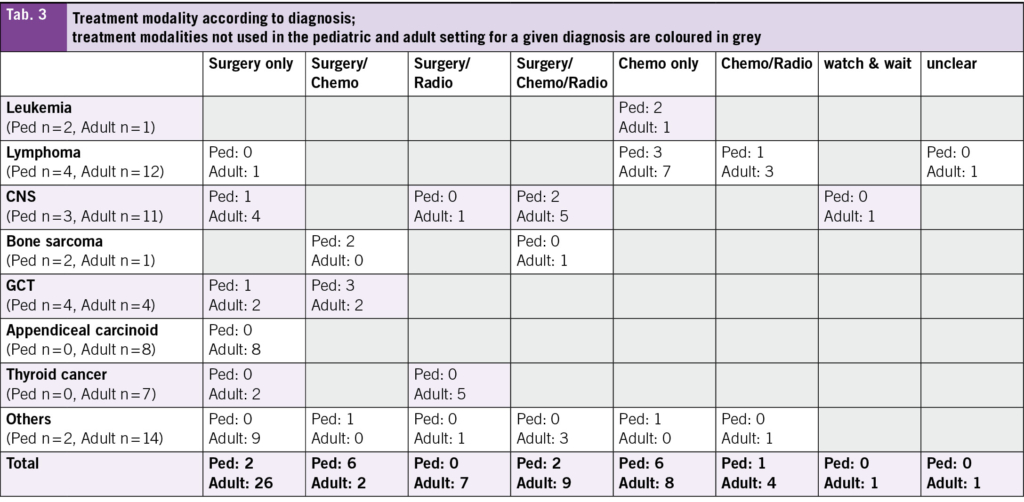

In terms of treatment modality, most patients treated at the adult hospital received surgery only (45 %) (Tab. 1). A detailed overview about the diagnoses and the treatment modalities used can be found in Tab. 3. Chemotherapy only and surgery plus chemotherapy were the most frequent modalities used in those treated in the pediatric hospital (35 % each).

Fertility counseling was offered to nearly two-third of patients at risk of infertility in both hospitals (adult 61 %, pediatric 69 %). In two patients in the adult setting and one in the pediatric setting, no counseling was offered because the treatment already started abroad. A larger proportion of patients treated with multimodal therapy received psychological support by psycho-oncology from the beginning in the pediatric hospital (93 % vs. 23 %) as was the trial inclusion rate into clinical trials (21 % vs. 3 %). For both of these comparisons, patients treated with surgery only were excluded.

Discussion

Our article provides insight into the epidemiological situation of AYA oncology patients treated either in the adult or the pediatric hospital in St. Gallen and assesses frequently proposed metrics to capture the performance of AYA care.

The heterogeneity between the pediatric and adult cohort is underscored by the different treatment approaches, where 45 % of patients in the adult cohort underwent surgery as the sole treatment modality, compared to only 12 % in the pediatric cohort. This heterogeneity reflects the differences in disease distribution and tumor biology across age groups, where 14 % of patients in the adult cohort were diagnosed with appendiceal carcinoid and 12 % with thyroid cancer. Both tumor types are primarily treated surgically. Additionally, a potential referral bias may exist, whereby adolescent patients aged below 18 years with tumors managed surgically only may not have been referred to the pediatric oncology service, neither to the cantonal hospital, but treated in a smaller hospital. Differences in treatment protocols between pediatric and adult settings for similar tumor entities may also contribute to the variation. For instance, in malignant testicular germ cell tumors, pediatric patients more frequently receive adjuvant chemotherapy than their adult counterparts (21, 22). These differences, in conjunction with the relatively small sample size, pose a challenge to directly compare both cohorts. Still, the assessment and analysis of the current situation is a crucial and important step when planning a new AYA unit, as discussed for example by Haines et al. (16).

Given the broad spectrum of tumor types in AYA cancer patients, strong collaboration between the teams of the pediatric and adult hospital is essential to ensure optimal care for AYA cancer patients. For example, AYA patients diagnosed with ALL or sarcomas, tumor types more often seen in pediatric patients, achieve better survival when treated according to pediatric protocols (23, 24). On local level, this close collaboration and exchange between the cantonal hospital St. Gallen and the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Switzerland already exists. Pediatric oncologists are present at the tumor boards, where sarcoma, CNS tumor, and malignant hematology patients are discussed. This already resulted in joint discussions with the patients if the adult and pediatric setting are considered equivalent treatment options and in referral to the pediatric or adult setting based on shared decision making. In the future, joint care on a separate AYA ward throughout the whole treatment journey is the goal.

Besides the structure of clinical consultations, inclusion into clinical trials is another important topic. AYA cancer patients are generally under-represented in clinical trials. The ESMO and SIOPE AYA position paper showed that only 5–34 % of AYA cancer patients are included into clinical trials (25). Our results show that the inclusion rate in the adult hospital is slightly lower, where the rate in the pediatric hospital is in line with the position paper. Still, also the inclusion rate in the pediatric setting is not satisfactory. Again, the heterogeneity of both cohorts complicates a comparison and could explain partly a lower inclusion rate in clinical trials in the adult setting with less trials available for named diagnoses in the examined period. In this context, we must acknowledge that the proportion of patients included in clinical trials very much depends on whether there is an open trial for the tumor in question at the given time or not. Several studies emphasized the need to prioritize AYA trial inclusion when designing new AYA units, which seems to improve the survival rate in this age group in the long-term (11, 26). Addressing the limited number of clinical trials available to AYA cancer patients is an essential challenge in equitable research access. In response to this challenge, the ACCELERATE Forum established in 2017 the Working Group on Fostering Age-Inclusive Research (FAIR) (https://www.accelerate-platform.org/fair-trials). FAIR is dedicated to highlight the significant barrier posed by the upper age limit of 18 years in pediatric oncology trials. This threshold, which represents eligibility for participation in pediatric trials, is not based on clinical or biological rationale. It is therefore considered arbitrary. The exclusion of AYA patients from trials due to their chronological age undermines the potential for age-appropriate, evidence-based treatment approaches and hinders scientific progress in this vulnerable population.

Fertility counseling must be given high priority in AYA cancer care, as this is a crucial issue for the patients, with far-reaching consequences if not conducted, particularly in the context of highly gonadotoxic treatment (27, 28). The timely offer of this counseling can be challenging for critically ill patients, as treatment often must start immediately following the diagnosis. Despite the importance of this subject, the proportion of patients having documented discussions about potential infertility in the literature was reported to be as low as 26 % (29). This proportion was much higher in our cohort, but it is not yet at 100 % for those at risk. This must be improved in the future. A dedicated AYA fertility program might help to increase the number of patients who receive fertility counseling significantly (30).

The need for psychosocial support and appropriate screening for psychological distress is high. The staff to patient ratio is often lower in adult hospitals, including psychological health care professionals (18, 31). This often results in a lower proportion of patients receiving psychological care and support in adult hospitals. In St. Gallen, all adult hematology and oncology inpatients are offered psychological support through psycho-oncology. If patients are initially or throughout treated mainly surgically, there might be no immediate psychological offer. However, the reasons for the relatively low proportion of patients with documented psycho-oncological support in the adult setting is not clear from the records. It was not possible to clearly categorize them into lack of patient interest, absence of the offer, or inadequate documentation. Differences in the underlying cancer diagnoses in both groups might explain the different proportions of documented psycho-oncological support in both hospitals. The proportion of patients declining support might be higher if the needed treatment is less intense. However, it was shown that an organized and well-coordinated AYA structure might lead to a higher rate of patients receiving supportive services, such as psychosocial support (32).

Awareness of the unique needs of AYA cancer patients is steadily increasing in Switzerland. This growing recognition is exemplified by the AYA working group within the Swiss Society of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology (SSPHO). This working group aims to improve AYA-specific care, promote awareness, and support the development of national clinical guidelines. In parallel, the Swiss Oncology and Hematology Congress (SOHC), established by the Swiss Society of Medical Oncology (SSMO), the Swiss Society of Hematology (SSH) and the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK), has, under the leadership of SPOG (Swiss Pediatric Oncology Group) and SSPHO consistently featured joint sessions on AYA oncology in recent years. The topics of the last two years included Hodgkin lymphoma, germ cell tumors, bone sarcomas, and CNS tumors. For the upcoming congress, the topics of rehabilitation, bone sarcomas, and a national AYA strategy are planned (www.sohc.ch). These initiatives underscore the rising national commitment to address the distinct clinical and psychosocial challenges faced by AYA patients and highlight the importance of cross-disciplinary collaboration in optimizing their care.

Our analysis provides a good overview of the current situation in the two oncological units in St. Gallen. Even though retrospectively conducted and the analyzed cohorts are heterogeneous, which makes a comparison difficult, the insights are useful in the planning of a new model of care for AYA patients, which might help in increasing the quality of care for these patients.

Conclusion

The findings of this article highlight the necessity of a dedicated AYA oncology unit to address key gaps in care. The observed heterogeneity of tumor types in AYA patients underscores the importance of collaboration between pediatric and adult oncology specialists. A dedicated AYA unit, prioritizing clinical trial participation, fertility counseling, and comprehensive psychosocial support, is essential to optimize care and improve long-term outcomes for this population.

Dr. med. Lukas Rudolf von Rohr 1,2

Dr. med. Christina Appenzeller 3

Dr. med. Thomas Lehmann 3

Prof. Dr. med. Christoph Driessen 3

Dr. med. Maria Otth* 1,4

Prof Dr. med. Katrin Scheinemann* 1,5

1 Division of Oncology-Haematology, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Switzerland, St. Gallen, Switzerland

2 Department of Oncology, Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Birmingham B4 6NH, UK

3 Department of Medical Oncology and Hematology, Cantonal Hospital St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland.

4 Department of Oncology, University Children’s Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

5 Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, University of Lucerne, Lucerne, Switzerland

* shared last authorship

Abbreviations

AYA Adolescents and Young Adults

ALL Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

CNS Central Nervous System

ESMO European Society for Medical Oncology

GCT Germ Cell Tumor

iAMP21 Intrachromosomal Amplification of Chromosome 21

SIOPE European Society for Paediatric Oncology

SOHC Swiss Oncology and Hematology Congress

SSH Swiss Society of Hematology

SSMO Swiss Society of Medical Oncology

SSPHO Swiss Society of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology

TBI Total Body irradiation

Key papers:

• Ferrari A, Stark D, Peccatori FA, Fern L, Laurence V, Gaspar N, et al. Adolescents and young adults (AYA) with cancer: a position paper from the AYA Working Group of the European Society for Medical Oncology (33) and the European Society for Paediatric Oncology (SIOPE). ESMO Open. 2021;6(2):100096.

• Ferrari A, Silva M, Veneroni L, Magni C, Clerici CA, Meazza C, et al. Measuring the efficacy of a project for adolescents and young adults with cancer: A study from the Milan Youth Project. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(12):2197-204

• Coccia PF. Overview of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(5):235-7.

• Gaspar N, Marshall LV, Binner D, Herold R, Rousseau R, Blanc P, et al. Joint adolescent-adult early phase clinical trials to improve access to new drugs for adolescents with cancer: proposals from the multi-stakeholder platform-ACCELERATE. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(3):766-71

• Wolfson JA, Kenzik KM, Foxworthy B, Salsman JM, Donahue K, Nelson M, et al. Understanding Causes of Inferior Outcomes in Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21(8):881-8

• Haines ER, Gan H, Kupelian A, Roggenkamp B, Lux L, Kumar B, et al. The Development and Implementation of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Programs: Teen Cancer America’s Strategy. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2024;13(2):347-51.

• Lewin J, Ma JMZ, Mitchell L, Tam S, Puri N, Stephens D, et al. The positive effect of a dedicated adolescent and young adult fertility program on the rates of documentation of therapy-associated infertility risk and fertility preservation options. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(6):1915-22

• Patterson P, Jacobsen RL, McDonald FEJ, Pflugeisen CM, Bibby K, Macpherson CF, et al. Beyond Medical Care: How Different National Models of Care Impact the Experience of Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2023;12(6):859-67

Copyright

Aerzteverlag medinfo AG

– Division of Oncology-Haematology, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Switzerland, St. Gallen, Switzerland

– Department of Oncology, Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Birmingham B4 6NH, UK

– Department of Medical Oncology and Hematology, Cantonal Hospital St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland.

– Division of Oncology-Haematology, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Switzerland, St. Gallen, Switzerland

– Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, University of Lucerne, Lucerne, Switzerland

The authors report no conflicts of interest in relation to this work.

- Unique challenges in AYA onncology: Adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer present with a broad range of malignancies and distinct biological and psychosocial needs, yet underserved due to the lack of dedicated AYA oncology units in Switzerland. Strong collaboration between pediatric and adult oncology teams is crucial to ensure optimal care.

- Gaps in clinical trial inclusion, fertility counseling, and psychosocial support: AYA patients are underrepresented in clinical trials, despite their potential to improve survival outcomes. While fertility counseling is offered to most at-risk patients, there is still room for improvement, as it is for psychological support in the adult setting

- Need for a dedicated AYA unit: The analysis underscores the necessity of a structured AYA care model to bridge current gaps. A possible AYA unit in St. Gallen could enhance collaboration, increase trial enrollment, and provide comprehensive fertility and psychosocial support, ultimately improving treatment outcomes and quality of life for AYA patients.

1. National Cancer Institute. Adolescents and young adults with cancer 2023. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/types/aya

2. Ferrari A, Barr RD. International evolution in AYA oncology: Current status and future expectations. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(9).

3. Barr RD, Ferrari A, Ries L, Whelan J, Bleyer WA. Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Narrative Review of the Current Status and a View of the Future. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(5):495-501.

4. Miller KD, Fidler-Benaoudia M, Keegan TH, Hipp HS, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for adolescents and young adults, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(6):443-59.

5. Close AG, Dreyzin A, Miller KD, Seynnaeve BKN, Rapkin LB. Adolescent and young adult oncology-past, present, and future. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(6):485-96.

6. Lee JW. Optimal therapy for adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia-current perspectives. Blood Res. 2020;55(S1):S27-s31.

7. Azim HA, Jr., Partridge AH. Biology of breast cancer in young women. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16(4):427.

8. Coccia PF. Overview of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(5):235-7.

9. Siembida EJ, Loomans-Kropp HA, Trivedi N, O’Mara A, Sung L, Tami-Maury I, et al. Systematic review of barriers and facilitators to clinical trial enrollment among adolescents and young adults with cancer: Identifying opportunities for intervention. Cancer. 2020;126(5):949-57.

10. Fern LA, Lewandowski JA, Coxon KM, Whelan J. Available, accessible, aware, appropriate, and acceptable: a strategy to improve participation of teenagers and young adults in cancer trials. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(8):e341-50.

11. Bleyer A, Tai E, Siegel S. Role of clinical trials in survival progress of American adolescents and young adults with cancer-and lack thereof. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(8):e27074.

12. Wolfson JA, Kenzik KM, Foxworthy B, Salsman JM, Donahue K, Nelson M, et al. Understanding Causes of Inferior Outcomes in Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21(8):881-8.

13. Keegan TH, Ries LA, Barr RD, Geiger AM, Dahlke DV, Pollock BH, et al. Comparison of cancer survival trends in the United States of adolescents and young adults with those in children and older adults. Cancer. 2016;122(7):1009-16.

14. Zebrack BJ, Corbett V, Embry L, Aguilar C, Meeske KA, Hayes-Lattin B, et al. Psychological distress and unsatisfied need for psychosocial support in adolescent and young adult cancer patients during the first year following diagnosis. Psychooncology. 2014;23(11):1267-75.

15. Fidler MM, Frobisher C, Hawkins MM, Nathan PC. Challenges and opportunities in the care of survivors of adolescent and young adult cancers. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(6):e27668.

16. Haines ER, Gan H, Kupelian A, Roggenkamp B, Lux L, Kumar B, et al. The Development and Implementation of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Programs: Teen Cancer America’s Strategy. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2024;13(2):347-51.

17. Osborn M, Johnson R, Thompson K, Anazodo A, Albritton K, Ferrari A, et al. Models of care for adolescent and young adult cancer programs. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(12):e27991.

18. Sironi G, Barr RD, Ferrari A. Models of Care-There Is More Than One Way to Deliver. Cancer J. 2018;24(6):315-20.

19. Hollis R, Morgan S. The adolescent with cancer–at the edge of no-man’s land. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2(1):43-8.

20. Ferrari A, Silva M, Veneroni L, Magni C, Clerici CA, Meazza C, et al. Measuring the efficacy of a project for adolescents and young adults with cancer: A study from the Milan Youth Project. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(12):2197-204.

21. Calaminus G, Schneider DT, von Schweinitz D, Jürgens H, Infed N, Schönberger S, et al. Age-Dependent Presentation and Clinical Course of 1465 Patients Aged 0 to Less than 18 Years with Ovarian or Testicular Germ Cell Tumors; Data of the MAKEI 96 Protocol Revisited in the Light of Prenatal Germ Cell Biology. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(3).

22. Kobayashi K, Saito T, Kitamura Y, Nobushita T, Kawasaki T, Hara N, et al. Oncological outcomes in patients with stage I testicular seminoma and nonseminoma: pathological risk factors for relapse and feasibility of surveillance after orchiectomy. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:57.

23. Gupta S, Pole JD, Baxter NN, Sutradhar R, Lau C, Nagamuthu C, et al. The effect of adopting pediatric protocols in adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in pediatric vs adult centers: An IMPACT Cohort study. Cancer Med. 2019;8(5):2095-103.

24. Ferrari A, Gatz SA, Minard-Colin V, Alaggio R, Hovsepyan S, Orbach D, et al. Shedding a Light on the Challenges of Adolescents and Young Adults with Rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(24).

25. Ferrari A, Stark D, Peccatori FA, Fern L, Laurence V, Gaspar N, et al. Adolescents and young adults (AYA) with cancer: a position paper from the AYA Working Group of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the European Society for Paediatric Oncology (SIOPE). ESMO Open. 2021;6(2):100096.

26. Gaspar N, Marshall LV, Binner D, Herold R, Rousseau R, Blanc P, et al. Joint adolescent-adult early phase clinical trials to improve access to new drugs for adolescents with cancer: proposals from the multi-stakeholder platform-ACCELERATE. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(3):766-71.

27. Morgan S, Davies S, Palmer S, Plaster M. Sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll: caring for adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4825-30.

28. Bibby H, White V, Thompson K, Anazodo A. What Are the Unmet Needs and Care Experiences of Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer? A Systematic Review. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6(1):6-30.

29. Quinn GP, Block RG, Clayman ML, Kelvin J, Arvey SR, Lee JH, et al. If you did not document it, it did not happen: rates of documentation of discussion of infertility risk in adolescent and young adult oncology patients’ medical records. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(2):137-44.

30. Lewin J, Ma JMZ, Mitchell L, Tam S, Puri N, Stephens D, et al. The positive effect of a dedicated adolescent and young adult fertility program on the rates of documentation of therapy-associated infertility risk and fertility preservation options. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(6):1915-22.

31. Ferrari A, Thomas D, Franklin AR, Hayes-Lattin BM, Mascarin M, van der Graaf W, et al. Starting an adolescent and young adult program: some success stories and some obstacles to overcome. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4850-7.

32. Patterson P, Jacobsen RL, McDonald FEJ, Pflugeisen CM, Bibby K, Macpherson CF, et al. Beyond Medical Care: How Different National Models of Care Impact the Experience of Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2023;12(6):859-67.

33. Ladoire S, Goussot V, Redersdorff E, Cueff A, Ballot E, Truntzer C, et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among the staff and patients of a French cancer centre after first lockdown: The canSEROcov study. Eur J Cancer. 2021;148:359-70.

info@onco-suisse

- Vol. 15

- Ausgabe 5

- Oktober 2025