- Updated Swiss Practice Recommendations for the Treatment of Acne

Introduction

Incidence and burden of acne

Acne is one of the most common skin diseases seen in everyday practice. About 75 % to 90 % of adolescents show some acne lesions and the disease is often persisting into adulthood (1, 2). Acne is not a disease of the modern age. Already in 1931, a Swiss study found a prevalence of acne of 88 to 99 % in young men and of 88 to 97 % in young women (3).

Acne is often judged as a natural part of growing up, as a simple and self-limiting disease. However, it is now recognized that in some patients, acne shows characteristics that generally can be found in chronic diseases, such as a prolonged course, a pattern of recurrence or relapse, and a manifestation in acute episodes or in outbreaks with slow onset (4). An update from the global burden of disease study 2013, published in 2017, found that skin conditions contributed by 1.79 % to the global burden of disease, measured in disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Acne is ranging in second place with 0.29 % of the total burden (5). In addition, many studies have shown that acne can be a psychologically damaging condition that lasts for many years (6–11). Acne may also cause scarring, which will even aggravate the negative psychological effects and the burden of this disease (4).

About 60 % of the adolescents affected by acne have a mild form (1). These patients, in general, treat their acne by using non-prescription preparations without consulting their physician. The remaining 40 % of acne patients seek medical advice and treatment (1).

Pathophysiology of acne

Different pathophysiological factors contribute to the development of acne. There is an increased activity of the sebaceous glands with modifications in quality and quantity of sebum production (seborrhea). Alterations in the differentiation of the follicular keratinocytes lead to hyperkeratosis. Hyper-colonization with Cutibacterium acnes is responsible for the formation of a biofilm, triggering an immune response (12, 13).

It seems that there are many more factors involved in the development of acne than expected. Already in early acne, lesions interleukin-1-alpha and T-cells can be detected. In addition, androgens, skin lipids as well as regulatory neuropeptides are part of this multifactorial process (1, 12–15). Androgens, especially dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate, cause a proliferation of follicular keratinocytes with microcomedo formation and hyperproliferation of sebocytes followed by an increased sebum production. Excess androgen activity in puberty causes inflammatory processes, which are intensified by neuroendocrine regulatory mechanisms, follicular bacteria, pro-inflammatory sebaceous lipids, as well as dietary lipids and smoking. It seems that insulin resistance as well as hyperinsulinemia also play an essential role in the development of acne. Increased levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 correlate with the total number of acne and inflammatory lesions (14).

Clinical features and severity

Acne is a polymorphic chronic inflammatory skin disease (16). In most cases, it is affecting the face. But frequently the back and chest are also involved. Clinically, open and/or closed comedones as well as inflammatory lesions, including papules, pustules and nodules, can be found. Often scarring and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation can be seen.

Rationale and objective

As many acne patients are treated by their general practitioner, there is a need for convenient, practical guidance on the management of acne. The objective of this publication is to provide an update of the Swiss recommendations published in 2020, based on a review of the current literature and expert consensus (17).

Methods

A group of hospital- and private practice-based dermatologists, specialized in acne, as well as an experienced general practitioner, have met to revise the available literature on acne and its treatment. Based on the literature and under the lead of the first author of this publication, several expert statements – for example, regarding grading of disease severity, treatment goals and treatment options – have been developed. Then, in a multi-step approach using the Delphi method, the whole group of experts has reviewed and revised the different statements until at least 80 % of the experts agreed to them (18). These statements (marked in italics) will be presented hereafter.

Practice recommendations on acne management

Determination of acne severity

Acne severity should be determined by a physician’s subjective method that assesses which lesions are predominant. In most of the cases, the subjective method is sufficient. To describe the treatment of acne based on the subjective method, the following classification was used in these recommendations: (1) mild, (2) mild to moderate, (3) moderate to severe, and (4) severe acne. Subjective assessment of severity is generally not very reliable because of high inter- and intra-rater discrepancies. However, its reliability can be improved using a picture-based support.

Definition of treatment success

There was consensus in the expert group that short-term treatment success is defined as more than approximately 50 % reduction of inflammatory lesions within 3 months. Resolution of non-inflammatory lesions may take longer. The long-term therapeutic goal for most patients is a “clear or almost clear” skin (clear = no lesions, almost clear = hardly visible from a social distance, a few comedones and papules). The time necessary to reach this goal depends on many factors. A major factor is the acne severity before treatment. As treatment success in acne can vary, therapeutic goals must be discussed with the patient. Patient satisfaction should be one of the main factors to determine treatment success.

Induction therapy

Induction therapy in mild acne

In mild acne, topical retinoids with low irritation potential (e.g. adapalene 0.1 %) should be used as induction therapy (16). Topical retinoids are the preferred substance because of their ability to suppress the formation of new microcomedones. They should be applied on the entire affected area, not on single lesions. In mild acne with predominantly papulopustular or inflammatory lesions, benzoyl peroxide (BPO) can also be considered as induction therapy. Azelaic acid can be considered as 2nd line topical therapy, e.g. for patients suffering from skin irritation, during pregnancy or if pregnancy is planned.

Induction therapy in mild to moderate acne

Induction therapy in mild to moderate acne should be performed either with a combination therapy OR with topical retinoid alone, switching to combination after 6–12 weeks, depending on the treatment success (16). The preferred treatment strategy is the combination of retinoid/BPO. If irritation is a problem, retinoid-BPO can be used intermittently, every other day, or a combination of tretinoin with clindamycin can be used. If there is a predominance of papulopustular acne, initiation with BPO/clindamycin or tretinoin/clindamycin is an option.

Induction therapy in moderate to severe acne

A combination of high-dose topical retinoid (e.g. adapalene 0.3 %) with BPO might be used for induction therapy in moderate to severe acne (19–21). In case of irritation, an alternative treatment should be offered, for example, the combination of tretinoin with clindamycin or BPO/clindamycin. The addition of a systemic antibiotic to a topical retinoid and BPO can be considered, e.g. if a patient wants fast symptom relief, if many inflammatory lesions are present, and to avoid scarring. This might also improve compliance with treatment.

Induction therapy in severe acne

Systemic isotretinoin is the current gold standard for induction therapy in severe acne, except in case of contraindications (16). Further indications for an induction therapy with isotretinoin are an early tendency for scarring, previous topical treatments with insufficient response, or a severe psychological burden due to the acne (22).

Isotretinoin dosage and treatment duration

The isotretinoin dosage should be titrated. After starting low, the aim should be to reach a daily dose of systemic isotretinoin of at least 0.5 mg/kg body weight or the highest tolerated dose. The target total dose of isotretinoin should be 120–150 mg/kg body weight, but may vary, based on acne severity. Patients should be treated until the skin is “clear or almost clear”. If the treatment goal is reached, therapy with isotretinoin should be continued for another 2 to 3 months without tapering, and then maintenance treatment should be initiated.

Recently, randomized controlled comparative studies revealed that low-dose regimens of oral isotretinoin (0.1–0.3 mg/kg body weight) were preferable in all types of acne due to its similar efficacy to conventional doses, but with fewer occurrences of clinical and laboratory side effects as well as a better patient satisfaction and compliance (23, 24). To note, studies with a continuous low-dose regimen had better efficacy in comparison to other regimens (intermittent or pulsed) of low-dose treatment (23, 25). In addition, starting at a low dose may prevent an acute inflammatory flare of acne, which can usually occur 3–5 weeks after beginning treatment, and also prevent scarring (26). However, a systematic review with meta-analysis of the literature showed that a dosage > 0.5 mg/kg body weight improves the probability of preventing relapse compared to low doses, although randomized trials focused on this topic are lacking (27).

Due to its side effects profile and to improve patient adherence, isotretinoin should only be administered by dermatologists and specialists with adequate experience with this treatment modality.

Contraindications as well as regular clinical and laboratory follow-up have to be strictly observed, and pregnancy prevention is of utmost importance (for more details, see chapter “Practice recommendations for monitoring“ as well as www.swissmedicinfo.ch).

Isotretinoin co-medications

Two randomised studies showed a faster and more effective response to treatment with isotretinoin if antihistamines were administered concomitantly (28, 29).

The muco-cutaneous side effects of isotretinoin can be reduced by concomitant administration of omega-3 fatty acids (1 g / day) (30).

Alternatives to isotretinoin

In case of contraindications to isotretinoin, or based on patients’ preference systemic antibiotics in combination with a topical retinoid plus BPO may be considered as second line treatment option in patients with severe acne.

For women with signs of hyperandrogenism, with SAHA syndrome, with adult acne as sign of peripheral hyperandrogenism, or with acne and an additional wish for contraception, a systemic treatment with antiandrogenic compounds may be considered. Contraceptives with antiandrogen activity and spironolactone in a dose of 50 to 100 mg/d (no contraceptive method required) are options. A recent clinical study, conducted in 133 adult women with moderate acne, showed, for the first time, that treatment with 150 mg spironolactone per day for 6 months is significantly more effective than 100 mg doxycycline per day for 3 months, and very well tolerated (31). Antiandrogenic drugs are not considered a first-line treatment in women with uncomplicated acne vulgaris, as flares upon discontinuation are not uncommon. They are contraindicated in men.

Another alternative to isotretinoin is dapsone (50–75 mg/day, not approved in Switzerland). Before treatment start, glucose-6-phosphat-dehydrogenase has to be checked. There is also an off-label topical formulation of dapsone available.

Use of antibiotics in induction therapy

Both topical and systemic antibiotics should only be used in combination with topical retinoids and/or BPO. If systemic antibiotics are used, doxycycline and lymecycline (which is less phototoxic) should be preferred over minocycline for the treatment of moderate to severe acne (32, 33).

Although minocycline has shown good efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe acne, it may cause severe drug reactions, and the risk-benefit profile must be assessed. In addition, a twice-daily administration regimen might affect patient’s compliance (34–36). Due to those reasons, minocycline is not considered as a first choice for acne treatment.

Maintenance therapy

Indication for maintenance therapy

Maintenance therapy is recommended in all patients, regardless of acne severity (19, 37). There was consensus in the expert group that when the long-term treatment goal “clear or almost clear” is achieved, a switch to maintenance therapy is recommended.

Choice of maintenance therapy

There was consensus in the expert group that the choice of maintenance therapy should always be based on severity of illness, duration of illness, current treatment and history of relapse.

In maintenance therapy, the use of a topical retinoid with/without BPO is recommended. Retinoids have a unique mode of action, reducing formation of acne precursor lesions (microcomedones) and limiting development of new lesions (19, 38). Retinoids maintain skin clearance and may prevent scar formation (39, 40). After successful treatment of moderate to severe acne, the preferred maintenance therapy is the combination of a retinoid with BPO (19). If a high dose of topical retinoid/BPO was used during induction therapy, a switch to a lower dose of topical retinoid/BPO or a retinoid alone can be considered for maintenance treatment.

The therapy regimen chosen can be applied daily or every other day. Azelaic acid is a good alternative for maintenance treatment. Combinations used for topical maintenance therapy should not contain any antibiotics, due to the potential risk of antibiotic resistance. In more complicated cases (e.g. for patients treated with oral isotretinoin), the choice of maintenance therapy may differ. Therefore, these cases should be managed by a specialist.

Duration of maintenance therapy

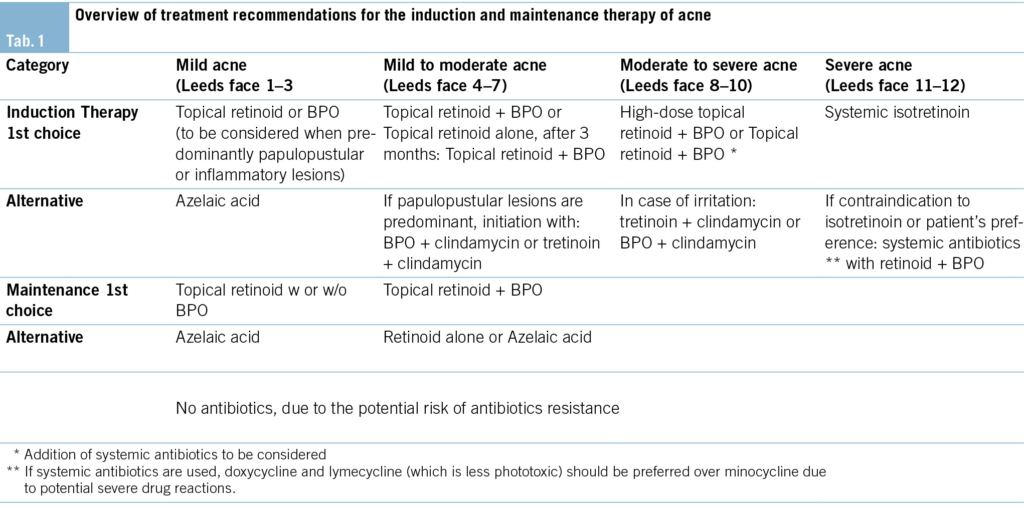

The experts group agreed that maintenance therapy should generally be continued for at least 6 months, and if necessary (e.g. in case of previous severe acne or some flares during maintenance therapy) up to 12 months or longer (16). (Tab. 1) provides an overview of treatment recommendations for Acne.

Treatment of truncal acne

For the treatment of mild forms of truncal acne, a topical retinoid or azelaic acid is recommended. In daily practice, the use of a BPO washing lotion has proven to be useful for its ease of application. For moderate truncal acne, trifarotene, the only topical option specifically approved for the treatment of truncal acne, can be used as well as topical combinations (adapalene/BPO). For severe truncal acne, systemic treatment is recommended (oral isotretinoin or tetracycline plus trifarotene).

Approximately 50 % of patients with facial acne also have lesions on the trunk (back and/or chest) (41). Often these lesions are not mentioned during a consultation. In a pilot study, azelaic acid 15 % foam was also found to be effective in treating moderate truncal acne (42). A small study with 15 patients found photodynamic therapy with topical 5 % 5-aminolevulinic acid to be effective in the treatment of truncal acne (43).

Treatment of adult acne

Mild cases of adult acne should be treated with a topical retinoid or BPO as monotherapy or in combination (also with topical antibiotics), with azelaic acid (allowed in pregnancy) and non-comedogenic skin care products. In persistent cases, low-dose oral isotretinoin, occasionally spironolactone/antiandrogens (only in female patients), are recommended (31, 44–45). To reduce the risk of relapses, prolonged therapies (> 6 months) are often required.

Acne in patients > 25 of age is called adult acne (45). If it starts in the adolescence period and continues, it is called “persistent acne” while if it develops for the first time after the age of 25 it is called ‘‘late-onset” acne. Adult acne is more commonly observed in females (45). The aetiopathogenesis involves genetic predisposition, chronic activation of the innate immune system, hormonal disorders (hyperandrogenism/insulin resistance) and external factors such as stress, Western-type diet, use of tobacco and cosmetics (45). Therefore, in cases of adult acne, the presence of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and hormonal imbalance should be ruled out.

Acne therapy during pregnancy / lactation

We recommend topical treatments as first-line therapy. BPO, erythromycin, the combination BPO/erythromycin, azelaic acid and salicylic acid 1–10 % are considered to be safe topical treatments for mild acne during pregnancy and lactation (46).

Moderate to severe acne may require systemic treatments, such as beta-lactam antibiotics (penicillin, cephalosporins) or macrolides (erythromycin) (47). For severe attacks, glucocorticoids may be indicated from the 2nd trimester onwards (48). Additionally, laser and light therapies (blue light, photodynamic therapy) may be considered as monotherapy or in combination with topical and systemic treatments (49, 50).

Both topical and systemic retinoids, tetracyclines (after the 15th week of pregnancy) and hormonal therapy are contra-indicated during pregnancy and lactation.

Prevention of scars

Effective treatment should include prevention of scars with early adequate treatment according to acne severity and individual tendency of scarring. Patients should be evaluated 3 months after treatment initiation to determine whether they have responded or whether further therapeutic options should be considered. It is the shared responsibility of the treating physician and the patient that acne is treated effectively to prevent acne scar formation (37, 39).

Topical as well as systemic retinoids can have a long-term effect in reducing acne scars (39, 40).

Skin care

Topical and systemic acne therapy has an irritation potential and may induce photosensitivity. It is important to discuss this issue with the patients in order to protect them from side effects and to ensure treatment compliance. It is recommended to apply topical retinoids and BPO in the evening.

Skin care should take into account patient preferences, age, acne severity, actual skin condition and concomitant drug therapy. Light formula moisturizing products (oil/water emulsion) should be preferred. Day and night skin care lotions have to be oil-free and should not contain comedogenic ingredients (e.g. paraffin). Emulsifier-free and fat-free lotions are most appropriate. Skin cleanser should be soap-

free (pH 4.5 to 5.5). Depending on the situation, the use of an oil-free sun lotion may be indicated.

A periodic physical comedones removal can be considered when open and closed comedones and inflammatory lesions are present. This should be particularly considered when starting treatment with oral isotretinoin to prevent flare up during the first weeks of isotretinoin treatment.

Energy-based devices in acne

Energy-based devices (EBD) are considered first-line therapy in the management of acne scars.

EBD are becoming increasingly popular in the treatment of acne. Studies show that lasers and other light-based methods have the ability to reduce acne. Due to the positive synergistic effect, they are usually combined with drug-based acne treatment.

Depending on the clinical findings, different lasers are used. Vascular lasers are the method of choice for inflammatory acne and flat or hypertrophic erythematous acne scars. Picosecond or Qs Nd:YAG lasers are used in particular for hyperpigmented scars or post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. Fractionated ablative and non-ablative lasers (non-AFL) are the choice for the management of atrophic acne scars (rolling scars and superficial box scars) (51).

The dogma that EBD treatment should be delayed until 6 months after discontinuation of systemic isotretinoin treatment has been revised in recent years (52–54). Several studies have found various EBD, including vascular lasers, non-AFL, and 1064-nm lasers to be safe and effective for acne and acne scarring either in combination with isotretinoin or starting within 1 month of completing isotretinoin (55–59).

Further counselling

The expert group recommends providing further counselling on nutrition, psychological aspects, stress, use of contraceptives, skin care, use of cosmetics, smoking and use of other drugs (like steroids) to the patient.

Nutrition

There are no known specific foods that would worsen acne.

According to a systematic review, factors like a high glycemic index, increased glycemic load, and carbohydrate intake have a modest yet significant proacnegenic effect (60).

Another systematic review and meta-analysis found zinc to be effective for the treatment of acne, particularly decreasing the number of inflammatory papules, when used as monotherapy or as an adjunctive treatment (61).

Practice recommendations for monitoring

Adherence

A treatment plan containing goals regarding acne severity/lesions and timelines should be agreed upon with the patient (62). Also, potential side effects should be explained to improve treatment adherence.

Pregnancy testing

It is the responsibility of the treating physician to ensure that a female patient of reproductive age receiving isotretinoin is not pregnant at the initiation of therapy, has understood that she must not become pregnant during therapy and up to one month after therapy, and that the patient is well aware of the risks of isotretinoin in pregnancy. This usually involves a pregnancy test at the initiation of therapy, the use of effective and reliable contraception, written information and extensive counselling at every visit. In exceptional cases, follow-up pregnancy tests and contraception during the treatment period can be omitted if there is no risk of pregnancy due to the circumstances.

Isotretinoin monitoring

In healthy patients with a normal baseline lipid panel and liver function test results, these tests should be repeated after 2 months of isotretinoin therapy. If findings are normal, no further testing may be required.

Routine complete blood cell count monitoring is not recommended. Due to the frequency of non-specific elevations in young people and the lack of therapeutic consequences, creatine kinase should not be determined routinely. Athletes should be informed that they should report if they suffer from muscle pain that differs from normal muscle soreness.

Quality of life

Quality of life is an important issue for patients with acne. It should be assessed and monitored in patients with acne, either by informal assessment during consultation or standardized instruments such as the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).

Referral to a dermatologist/other specialists

Severe forms of acne (including acne with a tendency of scarring, patients with acne conglobata or acne fulminans) should be referred to a dermatologist (or other specialist) for an expert opinion.

Further reasons for referral are:

• Patients with insufficient response after 3 months as defined in the recommendation

• Patients with frequent relapses

• Patients with severe acne and other dermatologic/rheumatologic symptoms (syndromal acne), acne in the context of virilisation or putative hormonal disorders

Expert referral may also be beneficial for patients showing non-compliance with acne therapy or for patients who are not satisfied with the therapy.

Conclusion

Acne is a frequently occurring skin disease. In many cases it is not just a self-limiting condition of teenagers. It is now recognized that acne shows some characteristics of a chronic disease and can have a severe psychological and social impact. Therefore, early and aggressive treatment is warranted, and maintenance treatment is recommended in all patients for optimal outcomes. The treatment recommendations presented here provide guidance for the choice of treatment options in acne of variable severity.

Funding Sources

The planning and organization of the authors’ meeting was funded by Galderma. The sponsor had no influence on the content of this work.

History

Manuscript received: 04.03.2025

Manuscript accepted: 25.03.2025

Severin Läuchli 1, 2, Florian Anzengruber 3, Antonio Cozzio 4, Laurence Feldmeyer 5, 13, Jean-Philippe Görög 6, Laurence Imhof 7, Martin Kägi 8, Beat Keller 9, Emmanuel Laffitte 10, Carlo Mainetti 11, Andreas Moser 12, Maya Wolfensperger 1, Nikhil Yawalkar 13, Andreas Zeller 14

1 Institute of Dermatology and Venerology, City Hospital Triemli, Zürich, Switzerland

2 Dermatologisches Zentrum Zürich AG, Zürich, Switzerland

3 Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Dermatology, Cantonal Hospital Graubuenden, Chur, Switzerland

4 Division of Dermatology, Venerology and Allergology, HOCH Cantonal Hospital St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland

5 Department of Dermatology, University Teaching and Research Hospital of the University of Lucerne, Lucerne, Switzerland.

6 Private Practice, Bern, Switzerland

7 Plastic Surgery Pyramide, Zurich, Switzerland

8 HautZentrum Zürich AG, Zürich, Switzerland

9 Dermapraxis AG, Wädenswil, Switzerland

10 Division of Dermatology and Venereology, Geneva University Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland

11 Private Practice, Bellinzona, Switzerland

12 novaderm SA, Affoltern am Albis, Switzerland

13 Department of Dermatology, Inselspital, University Hospital, Bern, Switzerland

14 Private Practice, Basel, Switzerland

Institute of Dermatology and Venerology

City Hospital Triemli Zurich

Gustav-Gull-Platz 5

8004 Zurich, Switzerland

severin.laeuchli@stadtspital.ch

Antonio Cozzio: Advisory board member for AbbVie, Celgene, Galderma, Lilly, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Leo

Laurence Feldmeyer: Advisory board member for Galderma, Leo

Jean-Philippe Görög: Advisory board member for Galderma

Laurence Imhof: Advisory board member for Galderma

Beat Keller: Advisory board member for AbbVie and Novartis

Emmanuel Laffitte: Advisory board member and/or speaker and/or investigator for AbbVie, Celgene, Galderma, Lilly, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Leo.

Severin Läuchli: Advisory board member and/or speaker and/or travel grants for AbbVie, Almirall, Galderma, Janssen, Meda, Novartis, Urgo.

Carlo Mainetti: Advisory board member for Galderma, AbbVie, Celgene, Eli-Lilly, Novartis, Sanofi.

Nikhil Yawalkar: Advisory board member for Galderma.

Martin Kägi: Advisory board member and/or speaker and/or investigator for AbbVie, Celgene, Galderma, Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Sanofi.

All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

These treatment recommendations provide practical guidance for the choice of induction treatment and maintenance therapy of acne; furthermore, the choice of therapy should be based on acne severity, duration of disease, current treatment and history of relapse.

1. Gollnick HP, Zouboulis CC. Akne ist nicht gleich Acne vulgaris (Not all acne is acne vulgaris). Dtsch Arztebl International. 2014;111(17):301-12.

2. Collier CN, Harper JC, Cafardi JA, Cantrell WC, Wang W, Foster KW et al. The prevalence of acne in adults 20 years and older. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(1):56-9.

3. Bloch B. Metabolism, endocrine glands and skin diseases, with special reference to acne vulgaris and xanthoma. British Journal of Dermatology. 1931;43(2):61-87.

4. Gollnick HP, Finlay AY, Shear N. Can we define acne as a chronic disease? American journal of clinical dermatology. 2008;9(5):279-84.

5. Karimkhani C, Dellavalle RP, Coffeng LE, Flohr C, Hay RJ, Langan SM et al. Global Skin Disease Morbidity and Mortality: An Update From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(5):406-12.

6. Niemeier V, Kupfer J, Demmelbauer-Ebner M, Stangier U, Effendy I, Gieler U. Coping with acne vulgaris. Evaluation of the chronic skin disorder questionnaire in patients with acne. Dermatology. 1998;196(1):108-15.

7. Thiboutot DM, Lookingbill DP. Acne: acute or chronic disease? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(5 Pt 3):S2-5.

8. Goulden V, McGeown CH, Cunliffe WJ. The familial risk of adult acne: a comparison between first-degree relatives of affected and unaffected individuals. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141(2):297-300.

9. James WD. Clinical practice. Acne. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(14):1463-72.

10. Kellett SC, Gawkrodger DJ. The psychological and emotional impact of acne and the effect of treatment with isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140(2):273-82.

11. Cunliffe WJ. Acne and unemployment. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115(3):386.

12. Zouboulis CC. Acne and sebaceous gland function. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22(5):360-6.

13. Zouboulis CC. (Pathophysiology of acne. What is confirmed?). Hautarzt. 2013;64(4):235-40.

14. Zouboulis CC, Eady A, Philpott M, Goldsmith LA, Orfanos C, Cunliffe WC et al. What is the pathogenesis of acne? Exp Dermatol. 2005;14(2):143-52.

15. Kurokawa I, Danby FW, Ju Q, Wang X, Xiang LF, Xia L, et al. New developments in our understanding of acne pathogenesis and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18(10):821-32.

16. Nast A, Dreno B, Bettoli V, Bukvic Mokos Z, Degitz K, Dressler C et al. European evidence-based (S3) guideline for the treatment of acne – update 2016 – short version. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(8):1261-8.

17. Läuchli S, Cozzio A, Feldmeyer L, Görög JP, Imhof L, Kägi M et al. Swiss practice recommendations for the treatment of acne. Derm Helv 2020;32(9):28-33

18. Linstone HA, Turoff M. The delphi method: Addison-Wesley Reading, MA; 1975.

19. Thiboutot DM, Dreno B, Abanmi A, Alexis AF, Araviiskaia E, Barona Cabal MI et al. Practical management of acne for clinicians: An international consensus from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(2 Suppl 1):S1-S23 e1.

20. Stein Gold L, Weiss J, Rueda MJ, Liu H, Tanghetti E. Moderate and Severe Inflammatory Acne Vulgaris Effectively Treated with Single-Agent Therapy by a New Fixed-Dose Combination Adapalene 0.3 %/Benzoyl Peroxide 2.5 % Gel: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Parallel-Group, Controlled Study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17(3):293-303.

21. Thiboutot D, Pariser DM, Egan N, Flores J, Herndon JH, Jr., Kanof NB et al. Adapalene gel 0.3 % for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled, phase III trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2):242-50.

22. Kägi M, Bindschedler M, Itin P, editors. Orales Isotretinoin zur Behandlung schwerer Akne vulgaris. Information und Empfehlungen. Swiss Medical Forum; 2008: EMH Media.

23. Legiawati L, Fahira A, Taufiqqurrachman I, Arifin GR, Widitha UR. Low-Dose versus Conventional-dose Oral Isotretinoin Regimens: A Systematic Review on Randomized Controlled Comparative Studies of Different Regimens. Curr Drug Saf. 2023;18:297-306.

24. Sadeghzadeh-Bazargan A, Ghassemi M, Goodarzi A, Roohaninasab M, Nobari NN, Behrangi E. Systematic review of low-dose isotretinoin for treatment of acne vulgaris: Focus on indication, dosage, regimen, efficacy, safety, satisfaction, and follow up, based on clinical studies. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:e14438.

25. Paichitrojjana Anon, Paichitrojjana Anand. Oral Isotretinoin and Its Uses in Dermatology: A Review. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2023;17:2573-2591.

26. Borghi A, Mantovani L, Minghetti S, Virgili A, Bettoli V. Acute Acne Flare following Isotretinoin Administration: Potential Protective Role of Low Starting Dose. Dermatology 2009;218:178–180.

27. Al Muqarrab F, Almohssen A. Low-dose oral isotretinoin for the treatment of adult patients with mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15311.

28. Pandey D, Agrawal S. Efficacy of Isotretinoin and Antihistamine versus Isotretinoin Alone in the Treatment of Moderate to Severe Acne: A Randomised Control Trial. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2019;17(65):14-19.

29. Lee HE, Chang IK, Lee Y, Kim CD, Seo JY, Lee JH et al. Effect of antihistamine as an adjuvant treatment of isotretinoin in acne: a randomized, controlled comparative study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol . 2014;28(12):1654-60.

30. Mirnezami M, Rahini H. Is Oral Omega-3 Effective in Reducing Mucocutaneous Side Effects of Isotretinoin in Patients with Acne Vulgaris? Dermatol Res Pract 2018:2018:6974045

31. Dréno B, Nguyen JM, Hainaut E, Machet L, Leccia MT, Beneton N et al. Efficacy of Spironolactone Compared with Doxycycline in Mode-rate Acne in Adult Females: Results of the Multicentre, Controlled,Randomized, Double-blind Prospective and Parallel Female AcneSpironolactone vs doxyCycline Efficacy (FASCE) Study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2024 Feb 21:104:adv26002.

32. Bjellerup M, Ljunggren B. Double blind cross-over studies on phototoxicity to three tetracycline derivatives in human volunteers. Photodermatol. 1987;4(6):281-7.

33. Bjellerup M, Ljunggren B. Differences in phototoxic potency should be considered when tetracyclines are prescribed during summer‐time. A study on doxycycline and lymecycline in human volunteers, using an objective method for recording erythema. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130(3):356-60.

34. Bienenfeld A, Nagler AR, Orlow SJ. Oral Antibacterial Therapy for Acne Vulgaris: An Evidence-Based Review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(4):469-90.

35. Ochsendorf F. Systemic antibiotic therapy of acne vulgaris. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2006;4(10):828-41.

36. Lebrun-Vignes B, Kreft-Jais C, Castot A, Chosidow O, French Network of Regional Centers of P. Comparative analysis of adverse drug reactions to tetracyclines: results of a French national survey and review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(6):1333-41.

37. Gollnick HP, Bettoli V, Lambert J, Araviiskaia E, Binic I, Dessinioti C et al. A consensus-based practical and daily guide for the treatment of acne patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(9):1480-90.

38. Dreno B, Gollnick HP, Kang S, Thiboutot D, Bettoli V, Torres V et al. Understanding innate immunity and inflammation in acne: implications for management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29 Suppl 4:3-11.

39. Levy LL, Zeichner JA. Management of acne scarring, part II: a comparative review of non-laser-based, minimally invasive approaches. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13(5):331-40.

40. Dreno B, Bissonnette R, Gagne-Henley A, Barankin B, Lynde C, Kerrouche N et al. Prevention and Reduction of Atrophic Acne Scars with Adapalene 0.3 %/Benzoyl Peroxide 2.5 % Gel in Subjects with Moderate or Severe Facial Acne: Results of a 6-Month Randomized, Vehicle-Controlled Trial Using Intra-Individual Comparison. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19(2):275-86.

41. Del Rosso J, Bikowski JB, Baum E, Smith J, Hawkes S, Benes V et al. A closer look at truncal acne vulgaris: prevalence, severity, and clinical significance. J Drugs Dermatol 2007; 6(6): 597-600.

42. Hoffman LK, Del Rosso JQ, Kircik LH. The Efficacy and Safety of Azelaic Acid 15 % Foam in the Treatment of Truncal Acne Vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol 2017;16(6):534-538.

43. Yew YW, Lai YC, Lim YL, Chong WS, Theng C. Photodynamic Therapy With Topical 5 % 5-Aminolevulinic Acid for the Treatment of Truncal Acne in Asian Patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(6):727-32.

44. Rocha MA, Bagatin E. Adult-onset acne: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2018 Feb 1:11:59-69.

45. Kutlu Ö, Karadag AS, Wollina U. Adult acne versus adolescent acne: a narrative review with a focus on epidemiology to treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2023;98(1):75-83.

46. Kong YL, Tey HL. Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation. Drugs 2013;73(8):779-87

47. Ly S, Kamal K, Manjaly P, Barbieri JS, Mostaghimi A. Treatment of Acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation: a narrative review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2023; 13:115-130

48. Schäfer T, Kahl C, Rzany B. Epidemiologie der Akne. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2010;8 Suppl1:S4-6

49. Diogo MLG, Campos TM, Fonseca ESR, Pavani C, Horliana ACRT, Fernandes KPS et al. Effect of Blue Light on Acne Vulgaris: A Systematic Review. Sensors (Basel). 2021;21(20):6943.

50. Boen M, Brownell J, Patel P, Tsoukas MM. The Role of Photodynamic Therapy in Acne: An Evidence-Based Review. Am J Clin Dermatol 2017;18(3):311-321

51. Salameh F, Shumaker PR, Goodman GJ, Spring LK, Seago M, Alam M et al. Energy-based devices for the treatment of Acne Scars: 2022 International consensus recommendations. Lasers Surg Med. 2022;54(1):10-26

52. Waldman A, Bolotin D, Arndt KA, Dover JS, Geronemus RG, Chapas A et al. ASDS Guidelines Task Force: Consensus Recommendations Regarding the Safety of Lasers, Dermabrasion, Chemical Peels, Energy Devices, and Skin Surgery During and After Isotretinoin Use. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43(10):1249-1262

53. Spring LK, Krakowski AC, Alam M, Bhatia A, Brauer J, Cohen J et al. Isotretinoin and Timing of Procedural Interventions: A Systematic Review With Consensus Recommendations. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(8):802-809

54. Prather HB, Alam M, Poon E, Arndt KA, Dover JS. Laser Safety in Isotretinoin Use: A Survey of Expert Opinion and Practice. Dermatol Surg. 2017 Mar;43(3):357-363.

55. Gold MH, Manturova NE, Kruglova LS, Ikonnikova EV. Treatment of Moderate to Severe Acne and Scars With a 650-Microsecond 1064-nm Laser and Isotretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19(6):646-651.

56. Gao L, Wang L, Li K, Tan Q, Dang E, Lu M et al. Treatment of acne vulgaris using 1,565 nm non-ablative fractional laser in combination with isotretinoin and pricking blood therapy. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(2):749-755

57. Xia J, Hu G, Hu D, Geng S, Zeng W. Concomitant Use of 1,550-nm Nonablative Fractional Laser With Low-Dose Isotretinoin for the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris in Asian Patients: A Randomized Split-Face Controlled Study. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44(9):1201-1208.

58. Ibrahim SM, Farag A, Hegazy R, Mongy M, Shalaby S, Kamel MM. Combined Low-Dose Isotretinoin and Pulsed Dye Laser Versus standard-Dose Isotretinoin in the Treatment of Inflammatory Acne. Lasers Surg Med. 2021;53(5):603-609.

59. Sapra S, Lultschik SD, Tran JV, Dong K. Concomitant Therapy of Oral Isotretinoin with Multiplex Pulsed Dye Laser and Nd: YAG Laser for Acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022 Sep;15(9):20-24.

60. Meixiong J, Ricco C, Vasavda C, Ho BK. Diet and acne: A systematic review. JAAD Int. 2022; 7: 95–112.

61. Yee BE, Richards P, Sui JY, Marsch AF. Serum zinc levels and efficacy of zinc treatment in acne vulgaris: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther 2020;33(6):e14252

62. Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, Bettoli V, Dreno B, Kang S, Leyden JJ, et al. New insights into the management of acne: an update from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(5 Suppl):S1-50.

PRAXIS

- Vol. 114

- Ausgabe 7

- Juli 2025